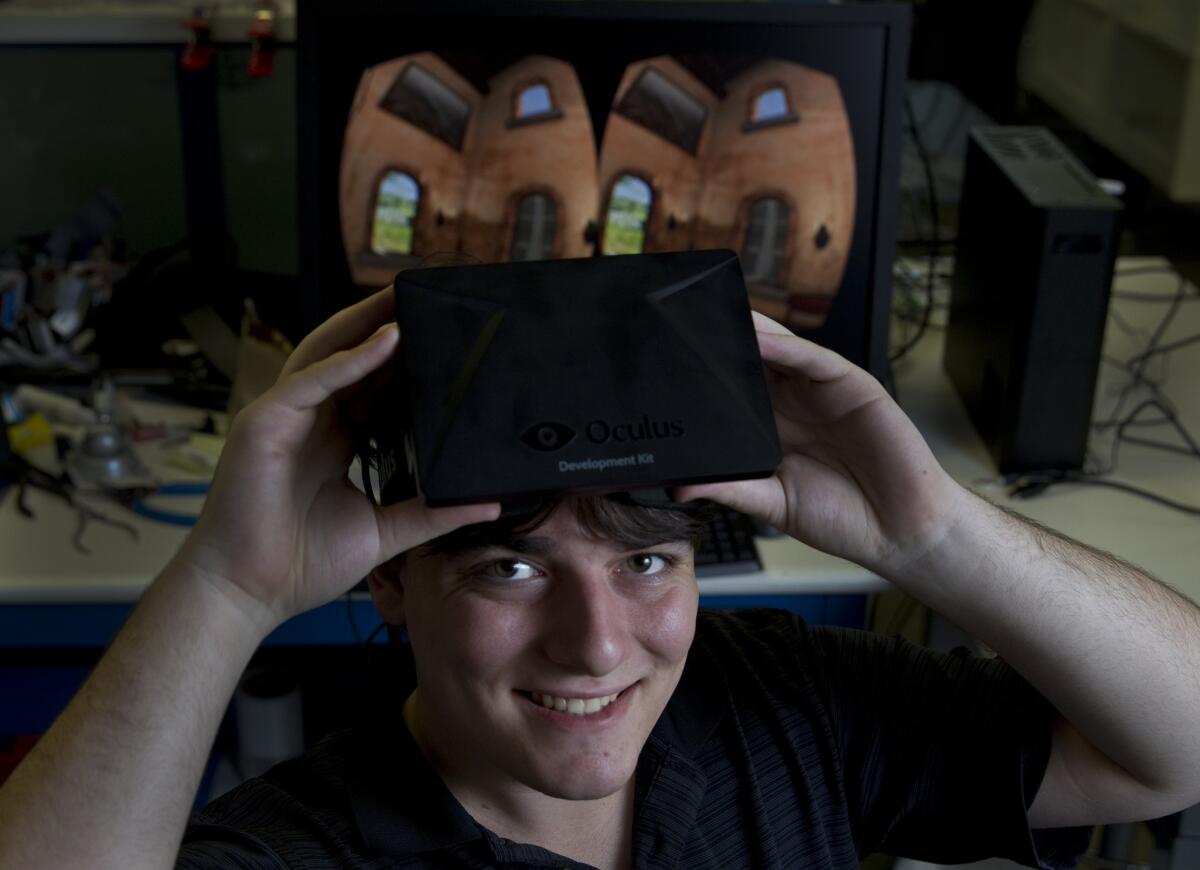

The Player: Palmer Luckey’s Oculus Rift could be a virtual reality breakthrough

Palmer Luckey, 20, founder, shown at his Irvine office, Oculus Inc., holds a new virtual reality machine he created called Oculus Rift, an upcoming low-latency, high field of view, consumer-priced virtual reality head-mounted display.

- Share via

The latest revolution in gaming may not be something related to in-home consoles or the much-hyped Google Glass. It may well come from a 20-year-old former journalism student who left Cal State Long Beach to focus on a longtime buzzword whose day may finally have come: virtual reality.

The idea sounds alternately futuristic and outdated now after briefly infiltrating pop culture in the ’90s, as witnessed by the fake playgrounds of the holodeck on “Star Trek: The Next Generation.” The concept’s latest form comes from California native Palmer Luckey, whose headset called the Rift has some of the top names in the video game industry convinced that virtual reality can again be the next big thing.

Skeptical? Luckey isn’t surprised.

“VR was popular in the ’80s and ’90s, and there was this promise that it was coming, but so many people got burned,” says Luckey, Rift designer and founder of Oculus VR. “People bring up the [Nintendo] Virtual Boy. It was terrible. It was one of the better things at the time, but people just remember it wasn’t a great experience.

“The technology wasn’t ready. Even if they did everything perfectly, they couldn’t possibly make a VR device that made consumers happy. It’s only in the past couple years that it has become possible to make a VR device that is low-cost and high-performance.”

And Luckey has steadily been lining up converts, including “Doom” developer-turned-Rift-champion John Carmack, longtime virtual reality researcher and game executive Mark Long, and Valve Corporation founder Gabe Newell, whose company has released such games as “Half-Life” and “Portal.”

With Tuesday’s launch of the yearly Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3) at the Los Angeles Convention Center, the largest video game trade show in the world, Luckey and his executive team will be arriving for private meetings with a slick, all-black device that resembles ski goggles.

“If you had asked me any other time, I would say, ‘Dude, we’ve been there and the tech was so disappointing that it ruined [virtual reality] for everyone,’” says Long, whose Meteor Entertainment has an Oculus Rift-ready version of its mech action game “Hawken.”

In the early ’90s Long was part of a team that built an abandoned virtual-reality headset for Hasbro, one that was canceled after what was said to have been a nearly $60-million investment. Oculus, says Long, “showed up with this head-mounted display that’s solved every problem, which was mostly comfort and psychophysics.”

Has VR’s time come?

For all its buzzed-about promise, the technology has long seemed just out of reach. As Luckey mentioned, Nintendo’s short-lived Virtual Boy was a notable flop, and a 1996 review in The Times noted it came with a high “migraine factor.” Once virtual reality disappeared from game systems, most headsets or simulators were relegated to the highest of the high-end uses. Think flight training or medical or military tools that cost thousands of dollars.

The Rift distinguishes itself by taking advantage of gains made by the mobile industry. Motion-control advancements better allow for head tracking and cut down on delays in response time, meaning the images on the Rift screen largely move with the tilt of the player’s head. Software is also now powerful enough to correct for lens distortion, and the advances made in the mobile market has helped make such technology affordable. Developer kits for the Rift have been priced at $300.

Twelve months ago the Rift was, in the words of Oculus Chief Executive Brendan Iribe, “dangling wires and circuit boards and duct tape and hot glue all over the place.”

Luckey at first didn’t intend the Rift to be a commercial product (a release date has not been set). His ultimate goal was to build a do-it-yourself kit and sell it via Kickstarter. Luckey would supply the circuit board, and you would supply the rest.

The plan changed when others got wind of the Rift, namely Carmack of “Doom” fame. Luckey was in constant communication online with those who hadn’t given up on home virtual-reality headsets, and Carmack wanted one of Luckey’s prototypes. Carmack showed it off at last year’s E3 and word got around.

It was soon suggested to Iribe that he check out the Rift. He was then an executive at cloud-streaming company Gaikai, which had just been sold to Sony for $380 million.

“It was an exciting-looking project, but it definitely looked a little bit like a high school science project,” Iribe says of his first meeting with Luckey.

How Luckey made it is something more akin to a happy accident. In fact, there were many accidents — Luckey has the scars to prove it.

Long before Luckey created the Rift, he concocted a device he liked to call “the melter,” which did exactly what you’d think. He was 5.

Palmer Luckey, 20, founder, shown at his Irvine office, Oculus Inc.

“It’s not,” Luckey clarifies, “like I learned that and I was on my way, but it was then that I learned that you could touch 9-volt batteries to steel wool and make fires.”

It wasn’t the first time his curiosity ran toward the more destructive side of technology. “For a long time I was really fascinated with high-voltage weaponry,” Luckey says. “From ages 11 to about 16, I got interested in building coil guns. So I built coil guns, Tesla coils, scion chargers — all these fun, dangerous, high-voltage projects. I got shocked a lot. Looking back, it’s honestly a miracle I am not dead.”

Right around this time in the story, it’s natural to wonder what Luckey’s parents thought of these potentially perilous experiments. Born and raised in Long Beach, Luckey was home-schooled by his stay-at-home mother. His father, a car salesman, allowed his son to use half of the family garage for his rudimentary engineering. They may have put a stop to it if they knew how dangerous some of it was, Luckey acknowledges, but good testing gave him a free pass.

“They were like, ‘Don’t shoot your eye out, kid,’” Luckey says. “I did all the standardized state testing just so they could make sure I wasn’t stupid.”

Ask Luckey if it was dangerous for a 14-year-old to be firing a nail through plywood with a coil gun, and he’ll wave you off. “Pyrotechnics are much more effective in transferring energy than something like a coil gun,” he’ll say. Then he’ll produce a scar near his right wrist that was the result of a “malfunction,” one that sent a high-voltage charge through his body.

Soon he switched to experimenting with lasers. “I just wanted to build things that you could hold in your hand, press a button and watch things catch on fire,” he says.

His new reality

But without a proper job and with no major allowance, Luckey needed an income to fund his hobbies. The release of Apple’s iPhone in the late 2000s would ultimately bring Luckey the cash he needed. Luckey says that when he was 16 he pulled in at least $36,000 by fixing iPhones and selling unlocked phones on Internet message boards for $700 apiece.

After building coil guns and lasers, his next project was to create the most immersive home game experience. With cash from his makeshift iPhone-fixing business, Luckey began snatching up any used virtual reality devices he could find.

So Luckey stalked EBay, hospital liquidation sales and government auctions. Luckey was shocked at how cheap old technology had become, noting he once bought what was a $97,000 virtual-reality device for $87.

The nonconsumer virtual-reality market was where Luckey, who was studying journalism at Cal State Long Beach, was potentially heading when he snared a job at USC’s military-associated Institute for Creative Technologies (ICT).

Luckey left journalism school and raised more than $2 million on Kickstarter to do what big-pocketed companies such as Nintendo and Hasbro failed to do years ago: make virtual reality a reality for the mass consumer market. Mark Bolas, the director of ICT’s Mixed Reality Lab, hired Luckey to work on a design team finding ways to make virtual reality cost-effective.

“The thing that set Palmer apart was he had a great knowledge of the history of virtual reality,” says Bolas.

That’s partly why Iribe was ready to cut Luckey a check the first time he met him, regardless of how unfinished the Rift looked. When he peered inside the device, Iribe remembers, “The hair stood up on the back of my neck.”

There was an immediate attempt to persuade Luckey to think more professionally. Iribe put in “a few hundred thousand as a personal investment” to fund Luckey’s Kickstarter.

“We thought it could go beyond VR enthusiasts,” Iribe says. “That’s where we got in the trenches with Palmer and thought about making a Kickstarter focused around [game] developers.” The Kickstarter was a success, with more than 9,500 backers that raised more than $2.4 million. For a $300 pledge, one received a development Rift kit, a pre-consumer version of the device aimed at those designing games.

“We’ve got 12 or 13 development kits,” says Jon Lander, an executive producer at CCP Games working on the popular online role-playing game “Eve Online.” The company has developed a space-fighting game for the Rift dubbed “Eve VR.”

“There’s a long way to go,” Lander says, “but the fact that we have so many of these kits and the quality is good enough to give you vertigo, that says we’re at the point of affordable, high-quality visuals which can actually transcend you from this mortal Earth into a virtual one.”

But perhaps the biggest surprise is that Luckey, who went to school be a tech journalist, was a missed meeting or unsent email away from writing about something like the Rift rather than founding a company behind it.

“What I wanted to do,” Luckey says, “was be a good tech writer who understood how things worked.”

For all of Luckey’s experience playing with fire, he still had a backup plan.

Follow me @toddmartens

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.