Ken Takemoto: East West Players’ Mr. Fix-It

- Share via

To understand why East West Players loves Ken Takemoto, ask about “the duck.” The fake fowl -- a Rube Goldbergian contraption he created for a 2008revival of “Pippin” -- shows just how clever, conscientious and cheap the 75-year-old prop master can be.

“Ken has spoiled us,” says Tim Dang, producing artistic director of East West, the nation’s leading Asian American stage company. “He can find almost anything, and what he can’t find he can make himself.”

A script doesn’t always describe what a prop should look like, he adds, “but Ken knows exactly what is wanted because he really listens to the play and the director. If we need picture frames, he knows what kind of frame the character would have and what period it should be.”

Theatrical property departments are responsible for securing and preparing every object the actors handle as well as providing decor items and accessories that help establish a scene’s sense of time and place.

“My role is to make a play feel authentic,” says Takemoto, whose 65th East West show -- “Cave Quest” -- runs through March 14. Usually, he’s happy if his work goes unnoticed: “What’s onstage should seem so natural no one knows what I did.”

But given the downtown theater’s cultural connections, he takes pride in hearing people talk about the accuracy with which he dresses a set. “I like when they say, ‘Oh, that looks like my auntie’s house!’ ”

Although prop people rarely get much glory, their ability to beg, borrow or build whatever they can’t afford to buy makes a big difference.

“What the audience may think are small things are things we depend on,” says “Cave Quest” director Diane Rodriguez, an associate producer and director of new play production for the Center Theatre Group. She notes that Les Thomas’ tale -- in which a video game creator visits an American Buddhist nun’s Tibetan hideaway -- “is challenging because it takes place in a very small, specific place. The nun has very few, very particular things she carried up or people brought. Ken helped root us in reality by creating a world that we really believe in.”

For “Cave Quest,” Takemoto tracked down or improvised a number of hard-to-find objects. The nun, for instance, needed a shawl of a certain color and texture that would look good under black light. The costume designer found fabric at a daunting $35 a yard. (The props budget was a few hundred dollars.) The ever-frugal Takemoto hit the thrift circuit: “I got the shawl at Goodwill for $4.95 and I got the senior discount.”

“When we saw what he had done,” says Rodriguez, “there was this moment of, ‘We are so happy you are here!’ ”

Besides his stagecraft skills, Takemoto is known for his generosity and a joie de vivre undimmed by age. The white-haired Hawaii native is decades older than most of his colleagues at East West, where he has worked as a free-lancer since 1989. “But he’s not a stodgy old person,” says Meg Imamoto, the company’s director of production. “Mr. T is everyone’s favorite uncle” -- albeit one who can get a bit feisty.

“Sometimes he’s Mr. Grumpy,” says actress Emily Kuroda. “But he’s got a heart of gold.” Takemoto has lent a hand -- once, even his house -- to many a small ensemble and struggling artist. “Someone couldn’t find a venue for a play,” Kuroda recalls, “and he emptied his bottom floor and let them put it on.”

“When I’m working, I can get stressed out,” Takemoto admits one recent afternoon as he relaxes between prop-shopping runs at his home, a tidy Craftsman in West Adams. “I just want everything to be right.”

As he sits in his living room smiling a grandfatherly smile, it’s hard to think of him as a grump -- or to guess he’s developed a nice side niche as an actor and dancer. After making his debut as an extra in an ‘80s-era Stevie Wonder music video, he has been active in TV and movies, playing a variety of what he calls “older Asian man roles” including a martial arts master and a retired kamikaze pilot. He also has appeared in commercials and print ads for products as varied as Oreos and Viagra.

“I like to keep busy,” he says. This month, in addition to “Cave Quest,” he just finished handling props for Grateful Crane Ensemble’s “The Betrayed,” which closed last weekend.

Up next are two Santa Monica productions -- he is prop master and costume designer for Ken Narasaki’s adaptation of the John Okada novel “No-No Boy,” which Timescape Arts Group will open March 27, and is rehearsing a dance piece with choreographer Keith Glassman that premieres April 2-3 at Highways Performance Space.

His hectic schedule may be his way of making up for lost time -- he didn’t get involved in theater until he was in his 50s. He grew up in Honolulu, the son of a cement mixer driver from Japan and a Japanese American dressmaker. After graduating with a degree in applied design from the University of Hawaii, he moved to Los Angeles, where he began teaching at Fremont High. Before he retired more than three decades later, he had taught at half a dozen campuses. “My goal was to experience working with kids of all different backgrounds,” he says.

In the late ‘70s, Takemoto started to study modern and Afro-Haitian dance. In 1989, he enrolled in East West’s summer conservatory, where he proved to be a natural when it came to props. At summer’s end, East West asked him to work on its revival of “Company.” “From there,” he says, “I kept going.”

When he begins a production, he attends readings and meetings with the director and designers. “I see whether things are decorative or are going to be thrown around.” Even mundane pieces -- bowls or chopsticks -- must be carefully chosen based on historical accuracy and the play’s content and design.

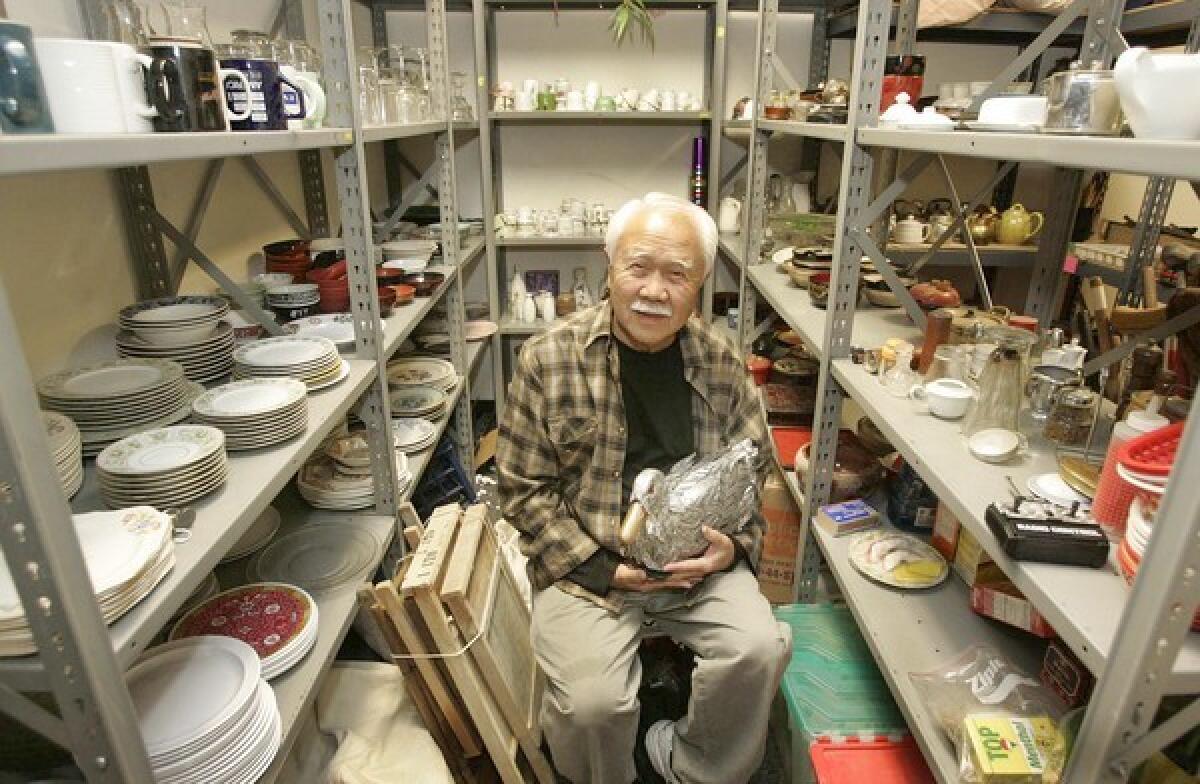

He searches for items in East West’s warehouse and a personal stash he accumulated at auctions, on overseas trips and by picking up stuff left at the curb. “We joke that if we throw something away, Mr. T climbs into the Dumpster and takes it home,” says Imamoto. He also scours secondhand shops and ethnic markets -- and whips up his own creations.

Not all of Takemoto’s gambits pay off. Once he sealed a roast turkey with polyurethane, hoping it would last through a play’s entire run. With a week to go, juices started seeping. “It was a mess,” he sighs.

He worked as art director for the 1997 Oscar-winning live-action short “Visas and Virtue.” He has designed costumes for East West six times, winning two Dramalogue awards, and has appeared in six East West productions, including Stephen Sondheim’s “Follies” and Philip Kan Gotanda’s “Sisters Matsumoto.”

“Ken has a striking look,” says Dang. “He has a certain character that comes through in his face and his persona that you don’t see a lot.”

As he heads into his late 70s, Takemoto, who is single, plans to continue acting. He isn’t ready to give up the life of a prop master either. While showing a visitor his home collection of treasures, he happily recounts past prop triumphs -- keeping an ear out for a call about his latest audition.

His favorite story is about the duck that now is part of East West lore. In “Pippin,” the hero experiences an epiphany after trying in vain to save a boy’s sick pet. Takemoto had to find a bird that could move from actor to actor and then keel over. Robots were expensive. Dolls were clunky. He finally hit upon the idea of mounting a wooden duck he got in Chinatown on a remote-control toy car that he could flip by forcing it to a sudden stop. He covered the creature with “feathers” made from flattened pieces of pie pan he meticulously embossed and colored using chopsticks and ink.

“It looked great and moved just how they wanted,” Takemoto says. “And it only cost $10 for the duck and $30 for the car -- and the pie pans were free.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.