‘Nomad’s Hotel’ by Cees Nooteboom

Cees Nooteboom, now 75, is one of the two Dutch writers -- along with his slightly older contemporary, Harry Mulisch -- whose name always turns up on those mysterious annual short lists of Nobel Prize contenders so beloved of European literary journalists.

Though the Netherlands’ native readership is small -- it sometimes seems there must be one interesting Dutch writer for every five Dutch readers -- both authors’ reputations have benefited greatly from their government’s enlightened program of subsidizing translations of the country’s contemporary writers. Abroad, both men are known primarily for their many novels but among Dutch-speaking readers, Nooteboom also is widely admired for his poetry and travel writing. “Nomad’s Hotel: Travels in Time and Space” is a selection of 14 such pieces written over 40 years with a brief introduction by the Argentine-born author Alberto Manguel.

As a young man in Buenos Aires, Manguel was fortunate enough to be invited into the small coterie of local literati who read daily to the blind Jorge Luis Borges. It’s the kind of experience that prepares one to appreciate Nooteboom, who has been compared not only to Borges, the great literary miniaturist, but also to Calvino and Nabokov. Nooteboom is, as Manguel points out, the sort of writer who can muse on whether the mathematical sum of all the room numbers of all the hotels in which you’ve ever stayed might “contain a coded message” regarding your destiny. He is a writer who can describe Irish grass as “idiotically green” and observe that not knowing the language of the country in which a traveler finds himself turns him “into a very small child, a dog, or a foreigner -- for these three are none of them capable of understanding what you say.” (The latter reaction came in a pub on the Aran Isles, where the author encountered his first native Irish speaker.)

The relatively short works here are not, in other words, pieces that slip easily into the conventional Anglo-American travel-writing genre. (That’s part of what renders them rather mesmerizing.) Nor does it work to label them “travel sketches.” Despite their brevity, these are deeply layered, richly allusive and -- in the best sense of the word -- demanding, wholly original pieces. Perhaps they best could be described as meditations on various destinations.

Take, for example, “Musings in Munich,” which begins: “Some cities live up to their responsibilities. They supply the traveler with the image he has of them, even if false.” Nooteboom’s progress through the Bavarian capital is hardly conventional, even when it involves a guided tour of the famous produce market. There’s an unspoken, but palpable subtext, since the author lived through the Nazi occupation of Holland and his father died during the war. Though no coarsely explicit connection is made, historical knowledge hovers like a cloud. Munich, after all, is where Hitlerism first claimed a substantial number of the German right’s fevered imaginations. The author looks back “almost 50 years now, a triumphal entry, more men, the uniforms a deeper more fundamental gray. That lot, they had worn helmets which practically covered their eyes, so that the face had disappeared and they had lost their personalities, exchanged them for an unbearable sameness. . . . “

Nooteboom’s constant Munich companion is the shade of philosopher Martin Heidegger who -- it has emerged in recent years -- was an academic collaborator with the National Socialists. His betrayal is the key to this piece’s specific theme of loss and, most particularly, the destruction of the fecund cultural compost heap that was Mitteleuropa: “That had been the end, an end that still went on and that, if his friends were to be believed, was about to be reversed. But, the traveler thought, the servants of the past do not travel well in the future. . . . “

A few pages on, Nooteboom remembers an American Thanksgiving spent in a white clapboard house on Maine’s Penobscot Bay with a group of elderly Central European émigrés. One, a Nobel Prize-winning biochemist, had asked the author to read to him -- Rilke, in German: “He had opened the book, yellowed, falling to bits, signs of nostalgia on every page, as the place where he was required to read from -- and he had read. The Americans had kept very quiet, he could hear the fire crackling in the grate, but he had not read for the others, just for that white head bent over and thinking of God knows what, something from 50 years before, when he had not yet been driven out or forced to flee; something old, and when he read, it was as if a globe with ancient air had been revealed and his own voice was mingling with that rarified, carefully preserved, ancient air.”

And when Nooteboom decides the time has come to leave Munich, he isn’t sure he knows it any better than when he arrived, but he wants to go south “in the wake of the migratory birds who woke him this morning. To another Bohemia somewhere, to the mountains -- the watershed of Europe -- where the languages, the states, the rivers flow in all directions, the part of his continent he loves the most, with its chaos of lost kingdoms, reconquered territories, colliding languages, clashing systems, the contradiction of valleys and mountains, the ancient splintered realm of the Middle.”

“Nomad’s Hotel” includes sojourns in Venice, Italy; parts of Africa; Mantua, Italy; Canberra, Australia; Zurich, Switzerland; and the pre-revolutionary Iranian city of Isfahan. One of the more recent pieces recounts two visits to the remote Aran Islands off Ireland’s west coast, where Nooteboom -- who has translated Synge, O’Casey and Behan into Dutch -- encounters a kindred spirit in Tim Robinson, an English mathematician and painter who has spent decades mapping the islands and setting down their Irish-speaking inhabitants’ stories. The author quotes him approvingly: “One should forgo these overluxuriant metaphors that covertly impute a desire of communication to nonhuman reality. We ourselves are the only source of meaning, at least on this little beach of the universe.”

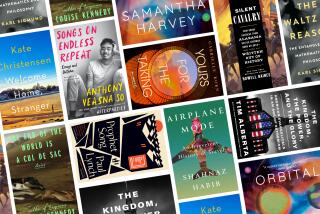

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.