Selling Stardom: Talent scams get short shrift from authorities, actors say

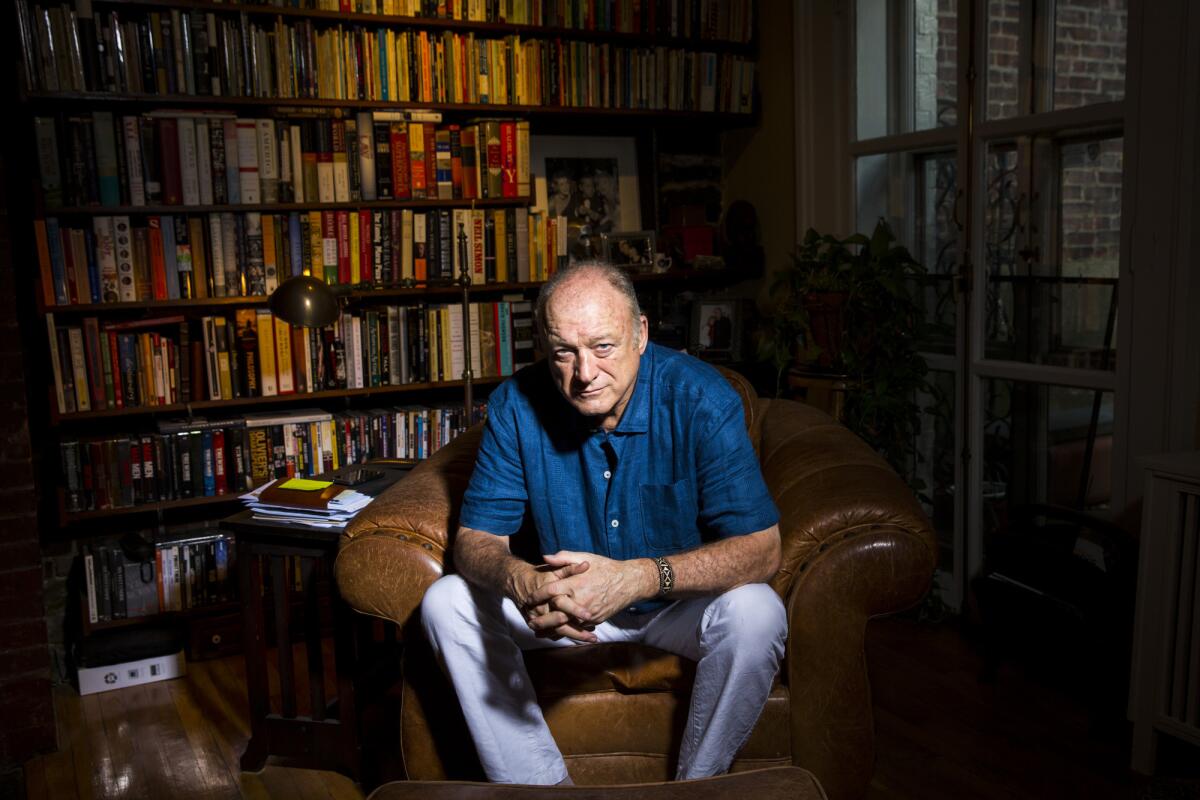

Actor John Doman, who starred in HBO’s “The Wire,” at home in Brooklyn, N.Y. Talent agent Peter Strain pleaded guilty to a felony charge in connection with the theft of earnings from Doman and two other clients.

- Share via

John Doman was filming on location in Prague when he learned that roughly $450,000 he was owed for his work on the TV series “Borgia” was missing.

His talent agent of more than two decades, Peter Strain, was supposed to hold the money on his behalf in a trust account and pay it out to the actor in installments.

Strain eventually pleaded guilty to a felony charge in connection with the theft of earnings from Doman and two other clients. But it wasn’t in a court in Los Angeles, where Strain resided and his company maintained an office.

Instead, Strain was convicted in a New York federal court last year after Doman’s lawyer said he was unable to interest the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office or the U.S. attorney’s office for Los Angeles in the case.

“Nobody wanted to do anything about it,” said Doman, 70, who starred on HBO’s “The Wire” and lives in Brooklyn. “It’s an industry town out there, and this is a guy stealing half a million dollars. I thought for sure they’d want to do something about that, but they didn’t.”

Prosecutors in Los Angeles declined to comment. Doman’s attorney, Miles Feldman, says local government lawyers told him it came down to resources.

“It is difficult for them to spend money on a case that could be resolved in a civil court — that’s what they explained to us,” Feldman said.

Doman’s experience illustrates what some actors and others working in the entertainment industry say is an indifferent attitude by Los Angeles authorities toward illegal or unscrupulous acts by talent agents and others who help performers secure work.

State and local officials have acknowledged that talent-related rip-offs are a big problem, passing at least five laws (including revisions to existing statutes) since 2000 to prevent abuses. The most significant legislation is the Krekorian Talent Scam Prevention Act, which went into effect in January 2010 and prohibits agents and others who represent performers from charging them any fees other than commissions and reimbursements for some out-of-pocket costs.

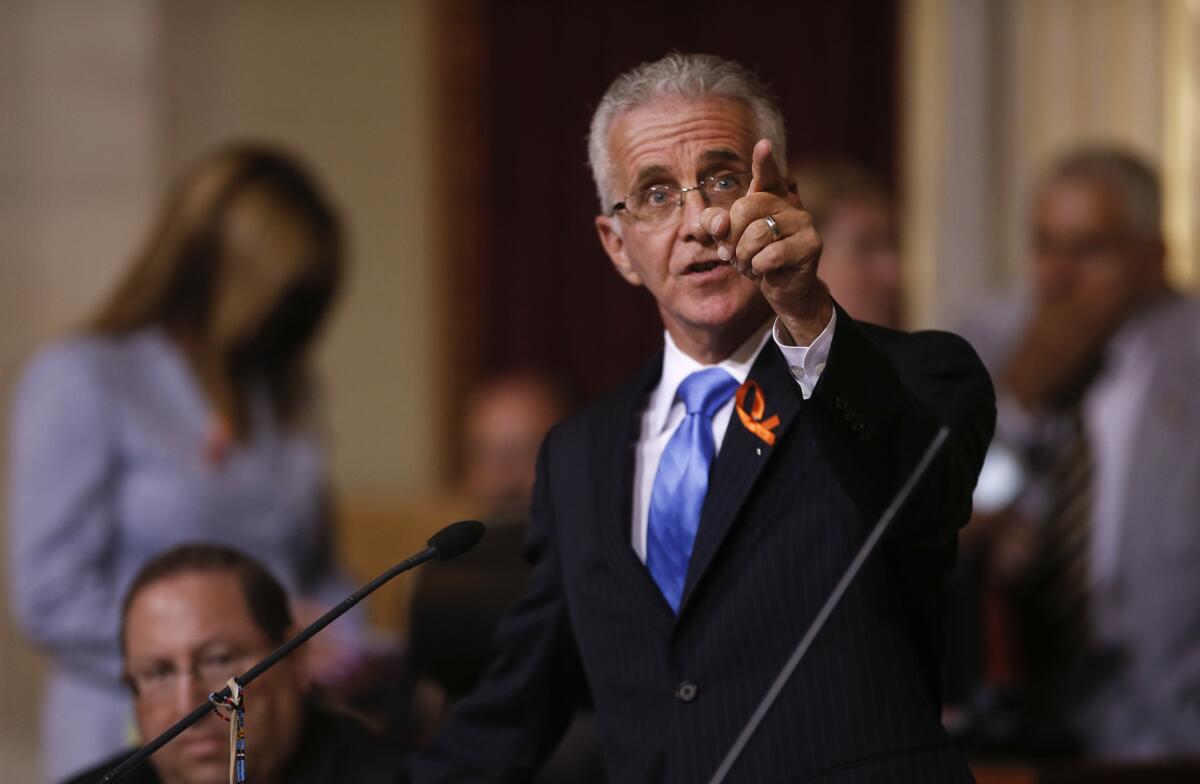

“With the unprecedented popularity of ‘American Idol’ and other reality television programming, the false promise of instant stardom has increasingly become a fertile ground for talent peddlers to scam the public, victimizing children and young adults in particular,” Los Angeles City Councilman Paul Krekorian wrote in 2009, when he was a state assemblyman spearheading the legislation targeting the abuse.

Paul Krekorian says the “horribly cruel” and predatory nature of some talent-related schemes spurred him to champion the Krekorian Talent Scam Prevention Act when he was in the state Assembly.

Most of the A-list talent in Hollywood — including actors, directors and writers — is represented by one of the handful of major agencies in Beverly Hills and Century City such as William Morris Endeavor, Creative Artists Agency and United Talent Agency.

But there are hundreds of other talent agencies registered to do business in Los Angeles County, many of them clustered in the Mid-Wilshire district and on Ventura Boulevard in the San Fernando Valley.

Most are legitimate businesses, representing actors, singers, models and dancers. Body Parts Models, for example, has about 200 clients whose hands, eyes, legs, rear ends and other features are needed for everything from TV commercials to feature films.

“We are almost like an index of parts,” said owner Linda Teglovic, a former fashion model. “Not just perfect parts — all types of parts. Glamour hands. Hands that play piano. Hands that have arthritis.”

But entertainment industry trade groups and attorneys caution that some of the smaller companies that represent performers take advantage of unknown wannabes who are blinded by the prospect of stardom. The abuses include:

Charging illegal upfront fees — such as a monthly retainer — in exchange for representation. These payments are barred under the Krekorian Act, which has a criminal remedy: Each violation of the law is punishable by up to one year in jail and/or a fine of up to $10,000.

Misrepresenting their services. There are companies called talent listing services that have given some clients the impression they are talent agencies and have gotten aspirants to sign up for expensive and unwanted services. These companies have also allegedly used improper contracts — or none at all.

Operating without proper licenses or bonds. Agencies are required by law to have a state-issued license and carry a $50,000 bond. Some have operated without a license and not posted a bond with the state Labor Commissioner’s Office.

Stealing money. Performers have complained that smaller agencies take money that is supposed to be deposited in trust accounts and never pay them, as was the case in the Strain matter. (When an actor books a job, the producer typically transfers the fee to the performer’s agent — who holds it in trust and has 30 days to pay out the funds, minus a commission.) Because the amounts are typically small, prosecutors rarely file criminal charges — forcing actors to retain private counsel or seek relief in Small Claims Court.

“These scams just don’t squelch dreams, they take thousands and thousands of dollars from people,” said Los Angeles City Atty. Mike Feuer. “If that were allowed to go on unabated, it sends a very bad message about Hollywood, which isn’t true.”

Licensed talent agencies in Los Angeles County

There are nearly 500 talent agencies registered to do business in L.A. County, ranging from powerhouses such as a William Morris Endeavor and Creative Artists Agency to smaller companies that represent actors, singers, models, dancers and unknown wannabes.

But just six Krekorian Act cases have been prosecuted statewide — each by the Los Angeles city attorney’s office — and only one since 2012.

Earlier this year, Feuer’s office prosecuted Hollywood talent manager Debra Baum for charging clients fees in exchange for representation, a violation of the Krekorian Act. Baum, 54, recruited Reed Isaac, a 19-year-old aspiring singer, in a Beverly Hills hair salon and later also enlisted her sister, Veronica, an aspiring actress, the city attorney alleged.

The city attorney said Baum charged the Isaac family a total of $110,000 in fees to manage the women’s respective singing and acting careers. In July, Baum entered a plea of no contest to one of the four counts she faced and agreed to make restitution of about $91,000. She avoided jail time, instead agreeing to perform community labor.

Baum did not respond to requests seeking comment. The Isaacs could not be reached for comment.

Asked why there had been so few prosecutions, Feuer said the Krekorian Act has prevented illegal activity, touted a public awareness campaign his office launched this year and pointed to the low number of complaints his office has received — “a couple dozen complaints, or something of that nature.”

But it is difficult to quantify the total number of grievances made by actors about their talent representatives because there is no central clearinghouse for complaints.

A 2009 legislative analyst’s report that reviewed the bill that would become the Krekorian Act said that complaints about acting and modeling scams had doubled every year since 2006, and were expected to do so again in 2009.

The report said there were about 1,000 complaints during this time period, attributing the data to then-Los Angeles City Atty. Rocky Delgadillo. It also said there were an “additional 143,000 inquiries during that time.” A separate analysis prepared for the state Assembly attributed those same figures to the Better Business Bureau of the Southland.

That group was kicked out of the Council of Better Business Bureaus in 2013 amid allegations of pressuring businesses into paying for inflated ratings and is now defunct.

The Better Business Bureau of Los Angeles and Silicon Valley, which took the place of the closed organization, said it had no record of the figures cited in the legislative analyses. Feuer said “there is no way for me to independently validate the numbers” cited in the reports.

Various groups and agencies contacted by The Times, including SAG-AFTRA and the California Labor Commissioner’s Office, each said they receive dozens of complaints annually.

Feuer said that earlier this year his office began forwarding complaints it receives to the L.A. County Department of Consumer and Business Affairs, which investigates the grievances and sends them back to the city attorney’s office or other agencies if they are deemed to have potential for prosecution. The Department of Consumer and Business Affairs said that as of October it had received 20 talent-related complaints in 2015.

Attorneys in private practice say part of the problem is that, with limited resources, prosecutors are unlikely to pursue small cases in which the losses may be in the hundreds of dollars and the victims might be seen as naive, chasing a near-impossible dream of stardom.

But others argue that, in spite of these obstacles, this is something that Hollywood needs to crack down on.

“The entertainment industry is part of the lifeblood of Los Angeles. I do think there would be a priority in making sure it is operating according to the law and people are not being taken advantage of,” said Loyola Law School professor Laurie Levenson.

Krekorian said that the “horribly cruel” and predatory nature of some of the talent-related schemes emboldened him to champion the legislation that bears his name.

“In some respects, the law has worked very effectively in changing the landscape of predatory talent schemes,” he said, claiming that after the Krekorian Act’s passage, some shady operators left the state or changed their tactics. “Now, does that mean that the problem is solved and there aren’t any more left in California? Of course it doesn’t. And that’s why we have to be vigilant about enforcement.”

But some observers said that because of prosecutors’ limited resources, many of the disputes involving talent representatives are best resolved via civil court.

That’s what Doman has tried to do. He successfully sued Strain in Los Angeles Superior Court in 2013 for breach of contract and other claims but said he’s been unable to collect on the judgment issued last year.

Doman directed his attorney to pursue a criminal case after filing the civil lawsuit. Ultimately, the U.S. attorney’s office for the Southern District of New York took it on.

The prosecutors alleged in a November 2013 superseding information that Strain — whose company, Peter Strain & Associates, also had an office in New York — used the money from clients to pay for more than $310,000 in artwork, more than $161,000 in jewelry and more than $57,000 in luxury goods.

He pleaded guilty in March 2014 to one count of interstate transportation of stolen property and was sentenced to three years’ probation, six months of home confinement and 500 hours of community service. Strain was also ordered to make restitution to Doman in the amount of $384,128.

But Doman said he has so far recouped just $17,000 of the money his former agent was directed to pay him in that case.

Strain did not respond to requests for comment.

Despite the imbroglio, Doman hasn’t soured on Hollywood, believing that operators like Strain are “bad apples in a sea of generally honorable people.” And he quickly signed with Paradigm Talent Agency after parting with Strain. That company is one of the biggest agencies in the business, with a stable of successful clients and gleaming Beverly Hills offices.

Still, Doman worries about less established performers.

“It’s a tough business to make it in, so young actors have to grab onto whatever they can grab onto to get a start,” he said. “Sometimes it’s a rotten apple.”

daniel.miller@latimes.com

Twitter: @DanielNMiller

One in a series of articles about selling stardom in Hollywood.

Additional Credits: Photography: Jay L. Clendenin. Research: Scott Wilson. Digital design: Lily Mihalik. Digital producer: Evan Wagstaff. Source for map: California Labor Commissioner’s Office, as of July 2015. (Angelica Quintero / Los Angeles Times)

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.