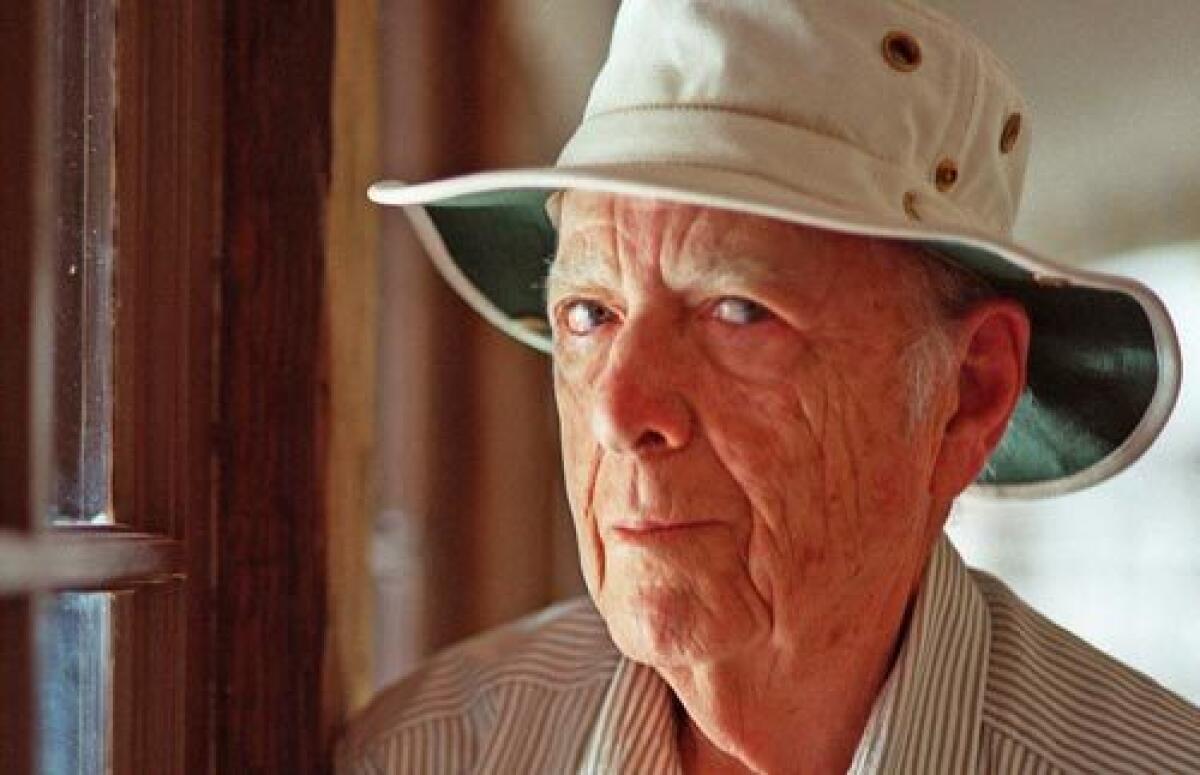

Author Herman Wouk’s spellbinding ways

- Share via

The Library of Congress will present its first Award for Lifetime Achievement in the Writing of Fiction to Herman Wouk on Wednesday night.

Now 93, Wouk has enjoyed six decades of unalloyed success. He won the Pulitzer Prize for his 1951 novel, “The Caine Mutiny,” ushered half a dozen of his bestselling books into film, theater and television adaptations, and has been honored on many previous occasions by the Library of Congress, where he conducted extensive research for his historical novels. During tonight’s festivities, he will formally donate his literary diaries, correspondence and many manuscripts.

OK, so obscure the man is not. Sen. John McCain calls “War and Remembrance” and “The Winds of War” his “two absolute favorite books.” “One of my life’s ambitions,” McCain told TheAtlantic.com in May, “is to meet Herman Wouk.”

I’ve never had the faintest desire to meet Herman Wouk, and it’s been years since I’ve read anything he wrote. I remember admiring but not loving his war novels. Nonetheless, in the early 1970s, when I was a young teen, four of Wouk’s books determined the course of my life. In fact, they ruined me.

I was already a greedy reader, giddy from the smell of the bookbinding glue at the Encino-Tarzana branch library, where my father imposed no limits as long as I remembered how many books I borrowed. My favorites had been V.M. Hillyer’s “A Child’s History of the World” and Louise Fitzhugh’s “Harriet the Spy,” for which I demonstrated my devotion by copying the entire volume into a notebook. (A generation later, my younger son did the same thing with the same book, except he typed it into his laptop.)

But the Wouk novels I found around our house were different. They were for me what blogger Patrick Brown on the Vroman’s Bookstore website has called “gateway drugs,” books that instigate a lifelong reading habit. Two were paperbacks and two were Book-of-the-Month Club selections that my parents didn’t have the time to read. Unlike lots of over-scheduled kids today, I had all the time in the world, the chief prerequisite for reading a Wouk novel. In my tetralogy of Wouk favorites, “Youngblood Hawke” clocks in at 792 pages and “Marjorie Morningstar” at 757, while “City Boy” and “Don’t Stop the Carnival” are comparatively svelte at 336 and 395 pages.

I loved these novels’ cozy reassurances that the pleasure they engineered would continue for a long, long time. On such childish delight, literary taste is often indelibly engraved: To this day, I still have high hopes for the longest books. Just as important, Wouk’s were the first books I read that were not marketed to children. Nothing thrilled me more than the glimpses he offered of the glamorous adult world, of martinis and evening clothes and New York City, a Disneyland of grown-ups. Here too were captivating descriptions of the world of work: of department-store owners and millinery-goods salesmen, theatrical publicists and naval officers, publishing executives and night watchmen. Even “City Boy,” told from an 11-year-old’s perspective, contains a crucial subplot concerning the family business, an ice-making plant known as “the Place.”

Nearly all of Wouk’s books feature at least one novelist: In “Youngblood Hawke” he is the hero; in “The Caine Mutiny” he’s Tom Keefer, the villain; in “Marjorie Morningstar” there are a couple of nebbishy fledglings. None of these depictions made me want to become a writer; that would come later. But the hours I spent with Wouk’s novels verified that I’d always be a reader and marked the beginning of my uselessness in any kind of work other than books.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.