David Wax Museum’s lively musical archive

In a way, it all comes down to the ass’ jawbone.

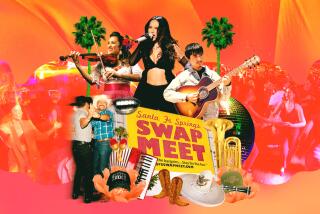

Students of musical Americana will hear plenty of rustic sounds when David Wax Museum plays Wednesday night at the Wiltern, including shades of folk, blues, rock and bluegrass, along with the Mexican regional varietals of son jarocho, son huasteco and son calentano. Guitars, fiddles, accordions and the Mexican jarana, a baroque eight-string cousin of the guitar, all are part of the Boston-based group’s lush instrumental mix.

But the object that tends to draw most attention when Museum’s core members David Wax and Suz Slezak perform is the quijada, or donkey jawbone, which emits an uncanny, vaguely spooky sound when grazed with a wooden stick. It’s an essential element of son jarocho, a musical form that combines classical Spanish lyrical structures, hothouse Afro-Caribbean beats, tricky 6/8 and 3/4 time signatures and insinuating, improvisational wordplay.

And although it wouldn’t raise an eyebrow in Veracruz or Xalapa, the quijada can elicit startled looks when David Wax Museum plays north of the Rio Grande.

“It really has been a signature feature, really a brand of our band, and most people have never seen it and they can’t believe you’re playing with an animal part,” Slezak says, speaking by phone last week from Virginia.

Making the exotic feel utterly organic is another of the group’s trademarks. At a cultural moment when it’s de rigueur for aspiring indie bands to sample everything from bossa nova to Inuit chants, David Wax Museum evinces not only a sincere interest in the eclectic traditions that it draws on but a deep, even scholarly, knowledge of them.

The band’s cross-breeding of Mexican regional strings and percussion, Appalachian high-lonesome harmonies, and a cosmopolitan, humorously confessional lyric-writing style that recalls Paul Simon, have earned approving nods from NPR, Time and the New Yorker. The Museum’s second, partially bilingual album, “Everything Is Saved,” and its ardent, hey-let’s-put-on-a-show performances at last year’s Newport Folk Festival, South by Southwest and other venues, have placed it alongside other hot American indies such as Langhorne Slim and the Old 97’s (which will share the Wiltern bill with Josh Ritter).

“There’s a certain joy and a certain playfulness and exuberance that I’ve found has been very important for me and the band to integrate into Americana,” Wax says. “There’s a certain joy in the rhythm that we’re trying to bring out in our band that has pushed me as a songwriter.”

Wax and Slezak, both on the cusp of 30, have impeccable homespun bona fides. Wax grew up near Columbia, Mo., where he started playing guitar and jazz piano and was exposed to the region’s vibrant bluegrass and folk-indie scene.

Later, both as a volunteer with the American Friends Service Committee and at Harvard University (where he studied Latin American history and culture), he spent several months living in the Mexican states of San Luis Potosí and Veracruz and jamming with some of the region’s master folk musicians. He also studied with a Mexican anthropologist, who taught him a catalog’s worth of huasteco and huapango folk songs.

“I went down without any idea about Mexican music at all,” Wax says. “It blew my mind. It was a turning point in a lot of different ways. I really got the bug about Mexico…. It was a really funny thing, I think, for a lot of people to have this gringo whose Spanish wasn’t perfect playing these Mexican folk songs.”

Slezak, who hails from near Charlottesville, Va., started playing fiddle when she was 7 and became part of a local family-run old-time music community (she’s also classically trained). Attending Wellesley College in suburban Boston, she played in a campus fiddlers’ group while majoring in anthropology.

Introduced to each other by mutual friends, Wax and Slezak quickly discovered they shared not only overlapping musical interests but a sibling-like ability to harmonize. They also found that the bluegrass, folk and jazz they’d been playing all their lives dovetailed nicely with son calentano‘s sweetly plaintive nostalgia for distant landscapes and lost loves, and son jarocho‘s rebellious energy (the Spanish Inquisition, scandalized by son jarocho‘s brazen eroticism, tried to ban it).

But it took a good deal of experimentation, Wax said, before the Museum could fully integrate Mexican regional rhythms and instrumentation into its own songs, such as “There Was a Bridge,” which is based on a huasteco tempo, or “The Great Unawakening,” which derives from another huasteco song, “El Guapo.”

“The evolution came together in a more mature way on the new record,” Wax says. “We tried to make it seamless, to make all the songs have a foot in both the Mexican and American traditions.”

Wax attributes the new record’s fluidity in no small measure to Sam Kassirer, a producer whose assured touch can be heard on records by Ritter and Erin McKeown. The border-hopping “Everything Is Saved” bounces from the cheerfully rueful “Born With a Broken Heart” to the jaunty romantic lament “Yes, Maria, Yes,” in which a meal of armadillo and huitlacoche (an indigenous corn-fungus delicacy) is proposed as an aphrodisiac.

Then there’s “Unfruitful,” a tonal cocktail of country-western and Weimar cabaret, sprinkled with eerie violin squeaks and spidery pluckings, that sounds like it might’ve been scratched out on a bar napkin by Kurt Weill, Merle Haggard and Tom Waits, to be recorded by the Band.

At bottom, though, Wax emphasizes, “It’s folk music. It’s not a real esoteric, difficult thing.”

“You can come to the band knowing a lot about what we do with Mexican folk music, and you can come not knowing anything.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.