Violinist Hahn-Bin has an antidote for ‘The Five Poisons’

- Share via

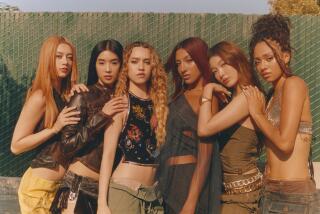

Resplendent in a Dior sleeveless kimono, Givenchy leopard-print tights and funky Rick Owens boots, the violin virtuoso Hahn-Bin brings to mind an ultra-chic Buddhist monk as he strolls through the Hammer Museum in Westwood. His eyes and lips, outlined in black, give his face a mask-like delicacy, and his tuft of black hair sweeps upward like a candle flame.

But despite his obvious flair for the dramatic, there’s nothing remotely standoff-ish about the 22-year-old musician and performance artist, who’ll appear Thursday night in “The Five Poisons,” a semi-staged cultural mash-up of works ranging from Chopin’s “Nocturne #20” to John Cage’s “In a Landscape,” in the Billy Wilder Theater.

“He’s so sweet,” gushes a Hammer staffer as Hahn-Bin poses for a Times photographer with the casual cool of a Milan runway model. “I think we’re all in love,” whispers Ann Philbin, the Hammer’s director, as she takes in the scene.

For Hahn-Bin (he goes by his first name), this sort of attention from art-world cognoscenti is both sudden and somewhat unexpected. In another time and place — say, Manchester, England, circa 1975 — Hahn-Bin might’ve metamorphosed into a glam-rock idol. Instead, the soloist, who was born in Seoul, South Korea, and moved with his family to Los Angeles at age 10, aspires to be nothing less than “the bridge between classical music, contemporary art and the mainstream popular culture,” a performer capable of, he says, making teenagers choose “Bach over Britney Spears.”

It’s an ambitious goal for an artist who has yet to release his first album in the United States. But as Hahn-Bin, a protégé of Itzhak Perlman, acknowledges with a laugh, “My name actually means ‘the shining star’ in Korean. So my parents certainly expected no less.”

Gentle in manner and soft of speech, Hahn-Bin says that “The Five Poisons” deals with a theme with great personal relevance: transcending the toxic emotions that swirl around us, and turning adversity to positive use. Divided into three “chapters” — “Ignorance,” “Anger and Pride” and “Desire and Jealousy” — the program traces a spiritual journey that Hahn-Bin links to his practice of Tonglin Buddhism.

“Certainly growing up I’ve had to deal with peoples’ poisons. And that always tends to begin with ignorance, and that’s why it’s Chapter One. Ignorance about human sexuality, ignorance about minorities, ignorance about race, gender. And because I was born a strange fruit, I always had to deal with it.”

In performance with pianist-collaborator John Blacklow, Hahn-Bin augments his violin playing with dancing and gestures (he does his own choreography), costume changes and even singing. The idea, he says, is for him to become a kind of spiritual avatar for his audiences, a bodhisattva, in Buddhist parlance, who suffers in order to release others’ pain. “In my role as an artist in this world I want to be the good toxin, I want to be the Botox to the wrinkles and dents in human heart.”

Hahn-Bin’s theatrical performance style places him in the company of contemporary classical music innovators such as the British violinist Nigel Kennedy and the American organist Cameron Carpenter, as well as with experimental, multi-disciplinary chameleons like David Bowie and Laurie Anderson. His recent gigs at venues such as the Morgan Library and Museum in New York and the Music Center at Strathmore in suburban Washington, D.C., reportedly have elicited startled gasps from older classical music aficionados, and thrilled reactions from his growing fan base of younger followers, who track his every move on Facebook and Twitter.

Reviewing the Strathmore performance last week, a Washington Post critic wrote that Hahn-Bin “engaged in slow-paced, eerie, total-body gesturing that strangely intensified the beauties of the music.”

It’s not hard to accept Hahn-Bin’s assertion that as a child and adolescent he always felt like a misfit. From an early age, music and fashion became the means by which he felt free to express himself.

“I never identified as a boy or a girl, I never identified as gay or straight, Asian American,” he says. “But a lot of people forced their vision of who I was onto me based on my appearance as I was growing up. So fashion really was a way for me to claim self-love, claim my own identity — to create Hahn-Bin.”

His mother, an artist, and his father, a music-loving civil engineer who “wanted to be the Korean Beatles,” and played everything at home from Freddie Mercury and Led Zeppelin to Mahler, encouraged their son’s right-brain tendencies. “They enrolled me in ballet classes, drama classes, violin lessons, drawing, painting, acting, you name it.”

He thrived creatively at Santa Monica’s Crossroads School, where he would turn up for classes in 5-inch Jimmy Choo snakeskin heels. But he struggled to make friends. “Kids would call me all these terrible names.”

Suddenly, Hahn-Bin’s speech halts and he struggles for a moment to regain his composure. When he resumes, his voice strains with emotion as he explains that “Five Poisons” was inspired in part by Asher Brown, Tyler Clementi and other youths who committed suicide, allegedly after they’d been bullied.

At 15, Hahn-Bin moved to New York to attend the Juilliard School. It wasn’t the best match. “Most of the things I was learning was about boundaries and about conforming and about fitting into the box.”

A saving grace during those years was studying with Perlman, whom Hahn-Bin calls “the first man in my life to accept me just the way I was.” Sometimes Hahn-Bin would show up for lessons with his face covered in black eye-liner imagery, hand-drawn tears streaming down his cheeks. Perlman “would just look at me, smile, and take a photo, and he would put it in his album.”

“He taught me everything I know about music, but more importantly he taught me how to love myself through music, and how to put everything that I felt into the music for the benefit of the audiences.”

As his career advances, Hahn-Bin hopes to follow the example of Perlman, Maria Callas and Vladimir Horowitz, artists who have what he calls “a true unique voice in the world” and communicate with “a large following in such a direct way.”

“It’s easy for many classical musicians to not be a creator, and more of a student of these great compositions,” he says. “It’s very tempting to forget your responsibility as an artist to the audiences when you are playing these amazing works.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.