Reels of classic films tend to melt into goo; philanthropist David W. Packard won’t let that happen

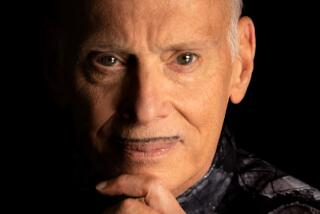

David W. Packard cares deeply about film history, and his Packard Humanities Institute has become one of the leading philanthropic organizations funding film preservation.

- Share via

If you care even a little about the art and history of American motion pictures, about being able to see classic films now and forever, you owe a debt of gratitude to David W. Packard.

Packard, the son of Hewlett-Packard co-founder David Packard, has never seen a Steven Spielberg movie and takes pleasure in reading Homer in the original Greek. But he cares deeply about film history, and his Packard Humanities Institute has become one of the leading philanthropic organizations funding film preservation.

See more of Entertainment’s top stories on Facebook >>

Now a landmark moment in that cause is nearing completion on 65 acres in the hills of Santa Clarita: a $180-million facility that houses vintage movies in the UCLA Film & Television Archive, including “The Maltese Falcon,” the Flash Gordon serials, Laurel & Hardy’s “Way Out West,” Cecil B. DeMille’s personal collection and producer Hal Wallis’ own print of “Casablanca.”

“UCLA was looking for a modest little place to move to, and I got involved and turned it into something monumental,” Packard, 75, said during an extended tour of the facility. “It’s a labor of love and a labor of craziness. I could have just built an adequate facility, but it didn’t cost that much more for it to be something wonderful.”

The Packard Humanities Institute, or PHI, prepares to officially open a $150-million facility in Santa Clarita known as the PHI Stoa. The new facility will house the UCLA film and TV archives.

The campus is designed primarily for storage, research and work related to film preservation, although there may be occasional semi-public events in one of the three screening rooms.

The facility is known as the PHI Stoa, for the Packard Humanities Institute and because the exterior resembles a type of classical Greek building known as a stoa, an outdoor colonnade structure supported by an impressive row of marble columns.

The interior is patterned after the 15th century Convent of Saint Marco in Florence, with offices resembling the cells of a monastery.

Packard, who rarely grants interviews, acknowledges that the design fits his style.

“I’m more like a monk; I like to do my work,” he said. “I don’t want to be a person who goes around boasting about doing things. What’s the point of that?”

The Packard Humanities Institute is nearing completion on 65 acres in the hills of Santa Clarita: a $180-million facility that houses vintage movies in the UCLA Film & Television Archive.

For moviegoers who want the classic films they love to be seen on the big screen by their children in the best condition possible, the stakes are enormous. It may seem films are forever, but history tells us this is not the case.

Nitrate-based negatives, Hollywood’s choice until about 1951, are notoriously unstable and over time often deteriorated to chemical goo, taking their one-of-a-kind images with them.

Before efforts like Packard’s, so many films were routinely lost or destroyed that it’s estimated that approximately half the films made before 1951, not to mention that more than eight of 10 features made between 1912 and 1930, no longer exist, according to film historians.

Talk to anyone in the film preservation world and you hear echoes of the words of James H. Billington, the recently retired librarian of Congress, who says: “If you want an analogy to David in American history, Andrew Carnegie would be the best.”

Packard’s institute financed a similar facility dedicated to film preservation outside of Washington, D.C., in Culpeper, Va. Built inside a disused Federal Reserve bunker that once held billions of dollars of shrink-wrapped currency, it includes nearly 90 miles of shelving, plus storage for highly flammable nitrate materials. It was donated to the Library of Congress in 2008.

The interior is patterned after the 15th century Convent of Saint Marco in Florence, with offices resembling the cells of a monastery.

“Frankly, I can think of no one and no institution which has done more for the cause of film preservation, specifically the preservation of classic American films,” than David Packard, said Jan-Christopher Horak, director of the UCLA Film & Television Archive.

“There are a lot of wealthy people in the film industry, but no one has stepped up to the plate the way David has. The amount of funding he has provided is staggering.”

About 90% of the films at PHI Stoa belong to the UCLA collection. They are stored in 120 nitrate vaults, built at a cost of $48 million.

Looking like cells in a 1930s big house movie, these structures are a chilly 38 degrees inside, with contents protected by an elaborate complex of anti-fire technologies, including exhaust ducts and a system called VESDA for “Very Early Smoke Detection Apparatus.”

“They’re the most modern nitrate vaults in existence,” Packard said. “This is not just buying five more years; they’re supposed to last centuries.”

During the tour, Packard’s infectious enthusiasm for film preservation and attention to detail were always on display. He noticed doors that didn’t function properly, pointed out cans of nitrate film that were not placed to take full advantage of heat-resistant shelving and clambered up a ladder to show off the building’s well-maintained interstitial space.

It broke up my friendship with Steve Jobs when I told him movies were not meant to be seen on 21/2 -inch screens.

— David W. Packard, philanthropist

Packard, who was intimately involved in the planning and building, takes pleasure in detailing exactly where in Italy the stone floor tiles, the marble columns, the handmade iron ceiling lanterns came from. He is so happy, in fact, with the work of the more than a dozen Italian subcontractors that he is planning to invite them and their families to the Stoa for a big, celebratory party this summer.

Enough of a film fan to have bought at auction the prop passport that Warner Bros. created for “Casablanca’s” Victor Laszlo, Packard emphasizes that “I don’t consider myself a funder, I’m a colleague who has resources to contribute. When there is something I’m interested in, I jump in with all five feet.”

If that sounds like an exaggeration, consider the specifics: When everything film-related that Packard and his foundation have contributed is added up, the total is close to half a billion dollars and includes the restoration of hundreds of films.

And because Packard believes passionately in the traditional theatrical experience, in screening as well as saving films, he has spearheaded the impeccable restoration of two vintage movie palaces: the California in San Jose and the Stanford in Palo Alto. The Stanford has been showing double bills that Packard (whose favorite actors include Ronald Colman, Audrey Hepburn and Cary Grant) has personally programmed since the late 1980s.

“It broke up my friendship with Steve Jobs,” he said, “when I told him movies were not meant to be seen on 21/2 -inch screens.”

The Packard Humanities Institute houses items including, “The Maltese Falcon,” the Flash Gordon serials, Laurel & Hardy’s “Way Out West,” Cecil B. DeMille’s personal collection and producer Hal Wallis’ own print of “Casablanca.”

A second-generation philanthropist whose family funded the Monterey Bay Aquarium without putting their name on it, Packard and his wife also founded the multibillion-dollar David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

“Something I inherited from my father is that once you decide to do something, just do it,” Packard said. “While you’re building something, you worry about how much money you’re spending on it, but when it’s finished, you only worry about whether you did a good job.

“What’s the point of cutting a corner? I’m lucky that I don’t have to, and if you can do it right, why not? Honestly, it doesn’t cost that much more to do it nicely, and people appreciate the opportunity to work in an environment where everyone wants to do things right.”

Packard founded PHI in 1987, but it really took off in 1998, when it received a major endowment grant from the foundation his parents began. Because he very much puts his money where his passions lie, Packard has funded a fascinating array of projects not only in film but in his two other main areas of interest, archaeology and music. “I’m really lucky,” he said, “I can help things I really care about.”

Hard as it is to believe now, Packard, with a PhD in classical philology from Harvard and immersed in a career as an classics academic at UCLA and other universities, once had total disdain for motion pictures. “I thought there was nothing to them; I looked down on them as degraded popular culture,” he remembered.

The campus is designed primarily for storage, research and work related to film preservation, although there may be occasional semi-public events in one of the three screening rooms.

He said that from ages 20 to 35 he saw just three motion pictures, all with Greek themes: “Never on Sunday,” “Zorba the Greek” and “Z.” Even today, with the exception of a passion for the works of the Indian director Satyajit Ray, whose Film & Study Center is relocating to the PHI Stoa, he pretty much avoids films made after 1960.

Packard’s conversion to classic cinema began when he taught at the University of North Carolina in the mid-1970s and, at the invitation of a friend, went to see a screening of “The Wizard of Oz” at a Judy Garland festival. He liked it so much that he went to see another Garland film, “Meet Me in St. Louis,” the next night.

“That was the most decisive moment in my life,” he remembered. “‘Meet Me in St. Louis’ somehow changed my life. And the next day I saw ‘A Star Is Born.’ That weekend was an explosion in my consciousness.”

Packard and his family moved back to Los Angeles, and he became a habitué of long-gone repertory houses like the Vagabond and the Tiffany and found out about the work of the UCLA archive, then directed by Robert Rosen, with Robert Gitt working as its first film preservationist.

“UCLA had these gorgeous nitrate prints off the camera negatives, and David fell in love with the work of Ernst Lubitsch, Josef von Sternberg and Billy Wilder,” says Gitt, who is now retired but still active in film preservation. “When David began funding, the major studios had not yet begun to preserve their own past; there was still a lack of interest in older films, so what he did was invaluable.”

Packard, for his part, has an equal admiration for Gitt’s impeccable preservation work, half-joking that he thought of naming the Stoa “the Gitty Villa.”

As his passion for classic film grew, Packard’s earlier love and knowledge of the classic Greek period, his understanding that, for instance, only a very small percentage of Sophocles’ complete plays (seven out of perhaps 120 written) survive today, unexpectedly informed his passion for saving cinema.

“Until a few years ago, I’d spent my whole life studying and teaching ancient Greek literature, looking back 2,000 years,” he said in a 1987 interview, just when his preservation work was beginning in earnest. “I wondered what people would see when they looked back at the 20th century, and I became persuaded that it’s going to be the Hollywood films of the ‘30s and ‘40s. A lot of my friends think I’m crazy, but I really do believe that. And it’s important that we preserve those films and not let them fade into obscurity.”

Packard has great plans for PHI’s collaboration with UCLA, including digitizing and making freely available to the public 27 million feet of Hearst newsreel footage the archive owns, and for the Stoa to possibly be the centerpiece of a historic preservation campus, but even as a stand-alone effort it is already doing a great deal.

“It may seem a little willful just to follow my instincts,” Packard said in as close as he wants to get to a summation, “but I’m in a position where I can. I’m a lucky guy who’s had the resources to support things I care about. I’m doing this because I love these movies and I want them to survive.”

ALSO:

10 movies we might be talking about at next year’s Oscars

Norway’s ‘The Wave’ shows Hollywood how to make a disaster film with real thrills

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.