Review: ‘O.J.: Made in America’ is so compelling you want it never to end ... even at 7-plus hours

- Share via

He was, perhaps, the most famous American ever charged with murder. His story saw the incendiary intertwining of numerous contemporary obsessions: sports, race, celebrity, crime, even sex. His trial lasted more than eight months and involved more than 100 witnesses, producing 45,000-plus pages of testimony, multimillion-dollar costs and books and movies too numerous to mention. But where O.J. Simpson is concerned, the best may well have been left for last.

“O.J.: Made in America,” is an exceptional seven-and-a-half-hour documentary, so perceptive, empathetic and compelling you want it never to end. Opening Friday in a one-week Oscar-qualifying run before appearing on ABC and ESPN next month, it is the O.J. project to watch if you are watching only one.

That’s because director Ezra Edelman has ambitiously both burrowed deeply into the story’s fascinating specifics and utilized those in the service of a bracingly wide perspective.

If FX’s recent dramatization “The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story” stuck closely to the case’s timeline, the documentary deals with O.J. after the trial and, more pointedly, goes back decades to fit his saga into the context of race and justice in Los Angeles, and, by implication, the rest of the country as well.

Like other way-long documentaries before it (Claude Lanzmann’s “Shoah,” clocking in at more than 10 hours, and Marcel Ophuls’ four-and-a-half-hour “The Sorrow and the Pity” come to mind), “Made in America” could not have accomplished all that without the cumulative power that results when that time is expertly used.

It’s not just that Edelman has talked to a lot of people, 65 of whom appear on screen, it’s that he mixes likely suspects and key courtroom players such as prosecutor Marcia Clark, defense lawyers F. Lee Bailey and Barry Scheck, L.A. police detective Mark Fuhrman and two members of the jury with unexpected commentators such as sports sociologist Harry Edwards, community activist Danny Bakewell, former New York Times sports columnist Robert Lipsyte and novelist Walter Mosely. (Prosecutor Christopher Darden, Judge Lance Ito and now-deceased lead defender Johnny Cochran are not in the interviewed group.)

More to the point, Edelman is a superb interviewer, displaying an ear for the good quote and an ability to get his subjects to relax and more or less level with him.

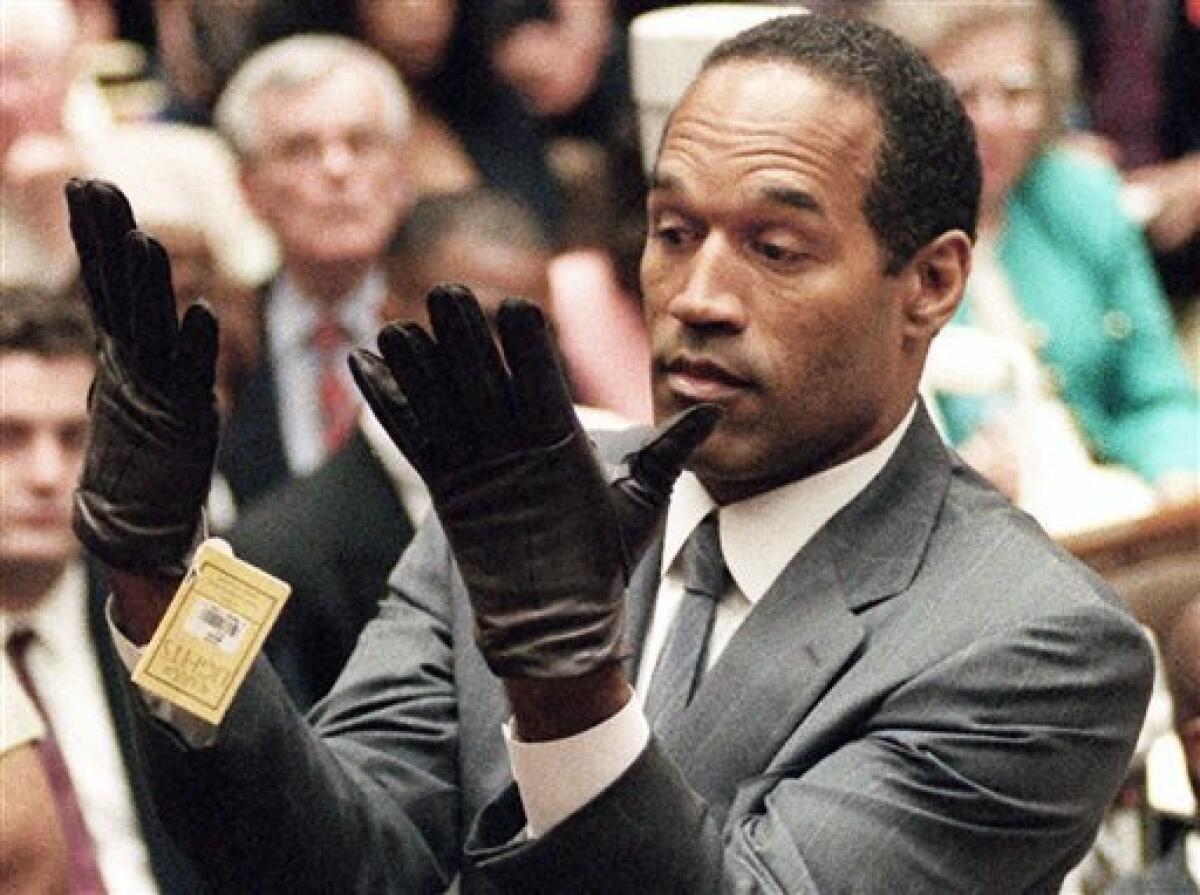

“Made in America” is filled with electric moments, like Scheck waffling about whether he actually believed his own arguments, O.J.’s former manager Mike Gilbert claiming he told O.J. before the courtroom glove scene that not taking his arthritis medicine would make his hands swell, and defense coordinator Carl Douglas exulting in changing the racial makeup of the photographs at O.J.’s Brentwood house to impress the largely black jury.

He told me, ‘I’m not black, I’m O.J.’ His quest was to erase race as the defining factor in his life.

— Harry Edwards

Edelman has a broader aim as well for his interviews, and that is conveying the devastating nature of the relationship between the system, as represented by the Los Angeles Police Department and the courts, and the black people who lived in South Los Angeles.

One after another, “Made in America” goes through the litany of unjust, even tragic situations. The killing of Eula Love over an unpaid gas bill, the wrecking of apartments at 39th and Dalton, the beating of Rodney King, the lack of prison time for the killer of Latasha Harlins, and more.

It all combined, L.A. County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas says, to show a disrespect for black life, to create the feeling, echoed nationwide today in the Black Lives Matter movement, that in Los Angeles skin color determines the degree of justice you get. By the time the trial began with a largely black jury, there was the sense that, as the Rev. Cecil Murray, former pastor of the First AME church says, “there was something bigger than him at stake.”

Which, finally, couldn’t be more ironic, because another major strand of “Made in America” details how little race mattered to O.J. “He told me, ‘I’m not black, I’m O.J.,’” recounts Harry Edwards, who adds “his quest was to erase race as the defining factor in his life.”

O.J.’s gifts as a running back were initially the key to this quest. Growing up poor (with, apparently, an absent gay father), in the Potrero Hill section of San Francisco, he was ambitious and eager for fame from an early age, a drive that when combined with his extraordinary football skills took him to USC and a Heisman Trophy. “He was seduced by white society,” says childhood friend Joe Bell. “He lost his identity; he didn’t know who he was.”

“Made in America” spends considerable time on O.J.’s football career, complete with dazzling clips, following him from that college success to the NFL’s Buffalo Bills, where his feat of gaining more than 2,000 yards in a 14-game season has never been duplicated.

These accomplishments are important because they led in part to O.J.’s feeling of exceptionalism, his sense that the way the world worked was irrelevant to him, something that emerged later in unexpected ways, such as a penchant for cheating at golf that many of his friends can’t help but grin and comment on.

In addition to being gifted, O.J. had enormous charm (“he made grown men melt,” is how one person puts it) and was not shy about putting it to use. He enjoyed being a celebrity, happily signing autographs for hours, and with his famous Hertz Rent a Car ads became perhaps the first black TV spokesperson to be effective with white consumers.

His relationship with Nicole Brown started with equal promise, though she was but 18 when they met and he was a married man with children. It was by all accounts a mutual attraction, with one of Nicole’s sisters testifying “they had a real love affair, that’s what makes things so sad.”

If one of the overarching themes of “Made in America” is that just as O.J.’s treatment by the murder panel could have been expected (“If this jury does convict me, maybe I did do it,” he is said to have joked to his defense team), so violence against Nicole could have been foreseen given the pattern of her 911 calls reporting abusive behavior (“He’s going to kill me,” she says on one call), which rarely resulted in legal action.

Especially good at detailing the various fiascos of the trial, from Mark Fuhrman’s racist tapes to the glove that wouldn’t fit, which negated considerable physical evidence, “Made in America” takes an almost surreal turn when it deals with O.J.’s sordid post-trial life in Miami and Las Vegas, culminating in a sports memorabilia robbery that led to his current incarceration in a Nevada prison.

“Please remember me as The Juice, please remember me as a good guy,” are the last words we hear from O.J., recorded in 1994 just before his famous white Bronco freeway drive.

For reasons “Made in America” brilliantly delineates, that is just not going to be possible anymore.

‘O.J.: Made in America’

No MPAA rating.

Running time: 7 hours, 30 minutes

Playing: Laemmle’s Monica, Santa Monica

Twitter: @KennethTuran

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.