NYFF 2014: In ‘Gone Girl,’ David Fincher tackles a mystery, and a marriage

- Share via

Reporting from NEW YORK — [Warning: Some descriptions in the below item could play the role of spoiler. Proceed at your own risk.]

Since it was announced several years ago that David Fincher would be directing an adaptation of Gillian Flynn’s “Gone Girl,” pundits have naturally explained it as the director’s Hitchcock turn, an auteur of the dark confronting one of the most talked-about mystery novels in years.

But, perhaps fittingly for a filmmaker who’s frequently subverted the thriller genre, the “Zodiac” helmer’s take on the 2012 bestseller is as much about marriage as it is a possible crime involving Nick and Amy Dunne. Fincher’s movie gives full weight, and then some, to the non-murderous themes that Flynn explored both in the novel and her script.

As it tells a time-jumping story of a couple that leave New York for small-town Missouri upon falling on economic hard times, “Gone Girl” offers plenty of thrills and turns. If you’ve read the book, you know about them; if you haven’t, best not to spoil those (particular) points.

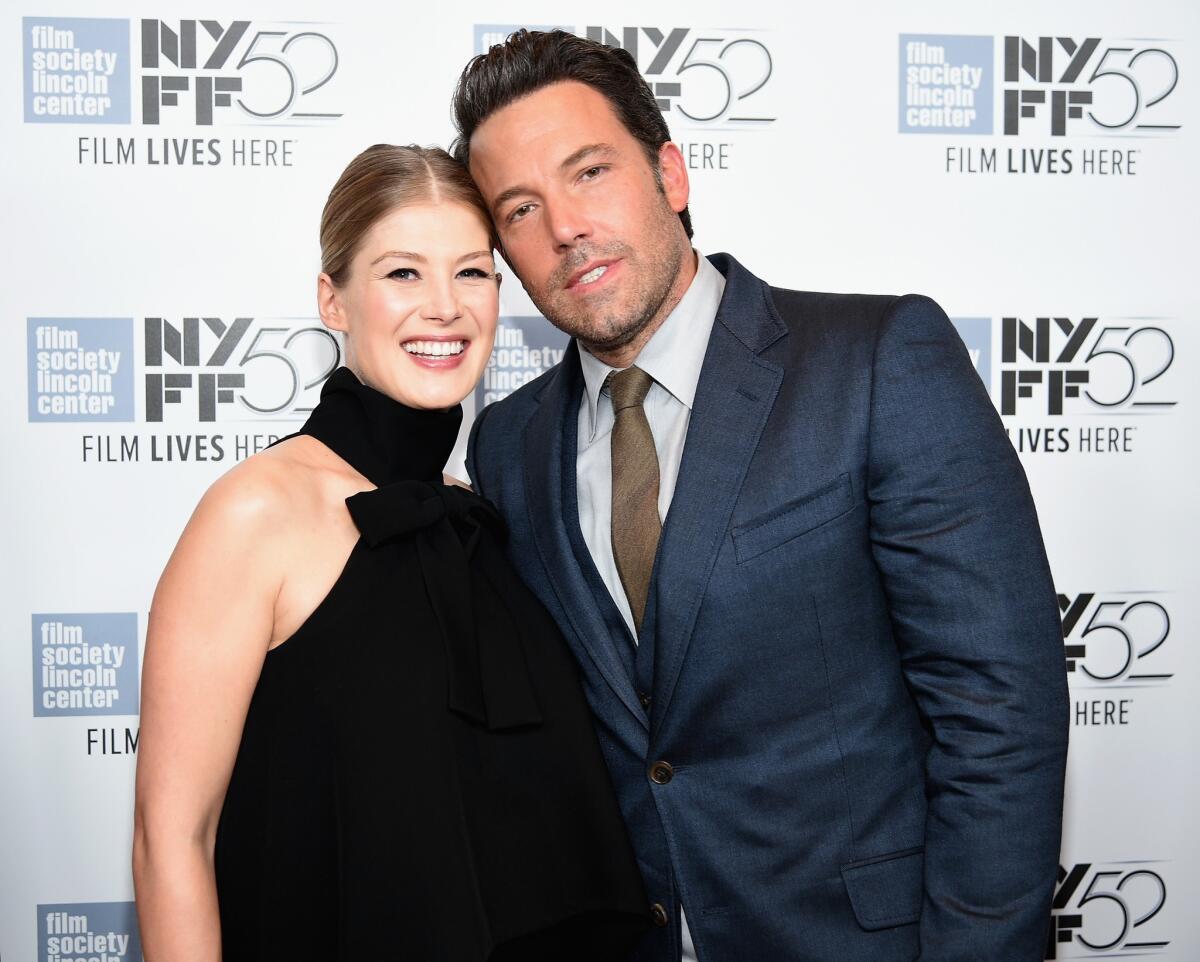

But in describing a romance that begins with shining promise and devolves so far that a husband is suspected of killing his wife, it also has marriage on its mind, underlined in several critical scenes, including one in which Nick (Ben Affleck) described the resentment he has for Amy (Rosamund Pike) and she replies, “That’s marriage.”

“It seems to me it’s about intimacy, really, the wonderful thing about intimacy and treachery of intimacy,” Pike said of the film on Friday.

Added Affleck: “The book asked really hard questions about marriage and relationships … and sometimes you find ugly things when you ask hard questions.” He added that he thought the book offered “Gillian’s dark take on marriage” and the film “David’s subversive take on Gillian’s dark take on marriage.”

Fincher and his cast unveiled the much-anticipated piece at a double whammy at the New York Film Festival on Friday evening, first at a combined press screening/press conference that saw the director, Flynn and many of his actors face the media for the first time, then at a glitterfest that followed during the opening night ceremony of Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall, where the film made its world premiere ahead of its commercial release next Friday.

The movie went over well at both screenings. “Gone Girl” opens with Nick the morning Amy goes missing (time in the present is marked by an on-screen count of “days gone”) and follows Nick as he moves from victim to suspect and through more than a few permutations beyond. The actor plays the post-disappearance period wiht apt stoicism, while flashbacks show he and Pike first during early romantic times and then in the struggles that followed. As it unspooled over its 2 1/2 hour running time, Fincher’s characteristically twisted, at times heightened, treatment elicited discussion, tension and even some laughter. (Neil Patrick Harris’ poker-faced creep was responsible for a chunk of the latter.)

But though unexpected supporting characters turn up throughout — e.g., Tyler Perry as a delicate mix of sharpie and confidante — it’s the to and fro between two main characters that dominates. Flynn said that in writing the script she was aware of the genre rabbit hole the story could go down, and worked “not to turn it into a whodunit but to keep the weird nuances and relationships intact.”

Or as Fincher, careful at the press conference in analyzing his own work, put it, it’s about what happens when someone says “I can’t get it up to be with you anymore.”

Studio Fox has high hopes for the film -- commercially, certainly, given the book’s popularity, but also on the award circuit. Fincher came close to the podium with two other films in recent years -- the 2008 release “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button” garnered more Oscar nominations than any film that year, while his 2010 picture “The Social Network” was a frontrunner for much of the season. Both films also scored Fincher directing nominations but no wins. (A few years ago his English-language version of “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo” broke his Oscar directing nomination streak, which gives him, and perhaps some voters, an added reason to propel this one along.)

The awards conversation is often sustained by a film’s water-cooler quotient, and “Gone Girl” offers a high degree of same. In its story of the vulture-y tabloids and the lemming-like public they (dis)serve, “Gone Girl” puts on the table plenty of questions about modern media; with characters meant to evoke a Nancy Grace-like scandal anchor, Fincher doesn’t shy away from the book’s media-circus aspects; at the presser he called out the “narrow bandwidth” of outlets trading in “tragic vampirism.” The film will generate plenty of punditizing on questions of celebrity and media spectacle, what with the subject already heavy in the air culturally, with similarly themed seasonal releases such as “Nightcrawler” and with “Gone Girl’s” own evocation of past films on the subject, particularly “To Die For,” which this film recalls in more ways than one.

On that last score, it’s worth noting that the film could also well generate a discussion about what position, if any, it takes on its female characters, especially its lead one. (If you know the book, you understand this; if not, suffice to say simple victim does not exactly suffice as a character description.)

There were already flashes of the discussion Friday night, amid some Tweets suggesting that the film could kick off a debate about misogyny. And while those who would argue that would seem to me to be missing the complexity of “Gone Girl,” a viewer’s gender could yet play a role in how characters are perceived. Affleck said he’s noticed after some early interviews that his Nick is something of a Rorschach test — “most women journalists are like, what’s it like playing a [jerk]. Most of the men just go, ‘Yeah,’” he said, with an approving note in his voice.

Pike similarly did not shy away from the film’s gender politics. “What I’m really interested is she couldn’t be a man. As much as people don’t want to hear that, the way her mind works is [particularly] female.” With big buzz and an equally large campaign, that question will soon be weighed by a wide audience, perhaps even a date one, men and women appropriately hashing out how a film handles relations between the two.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.