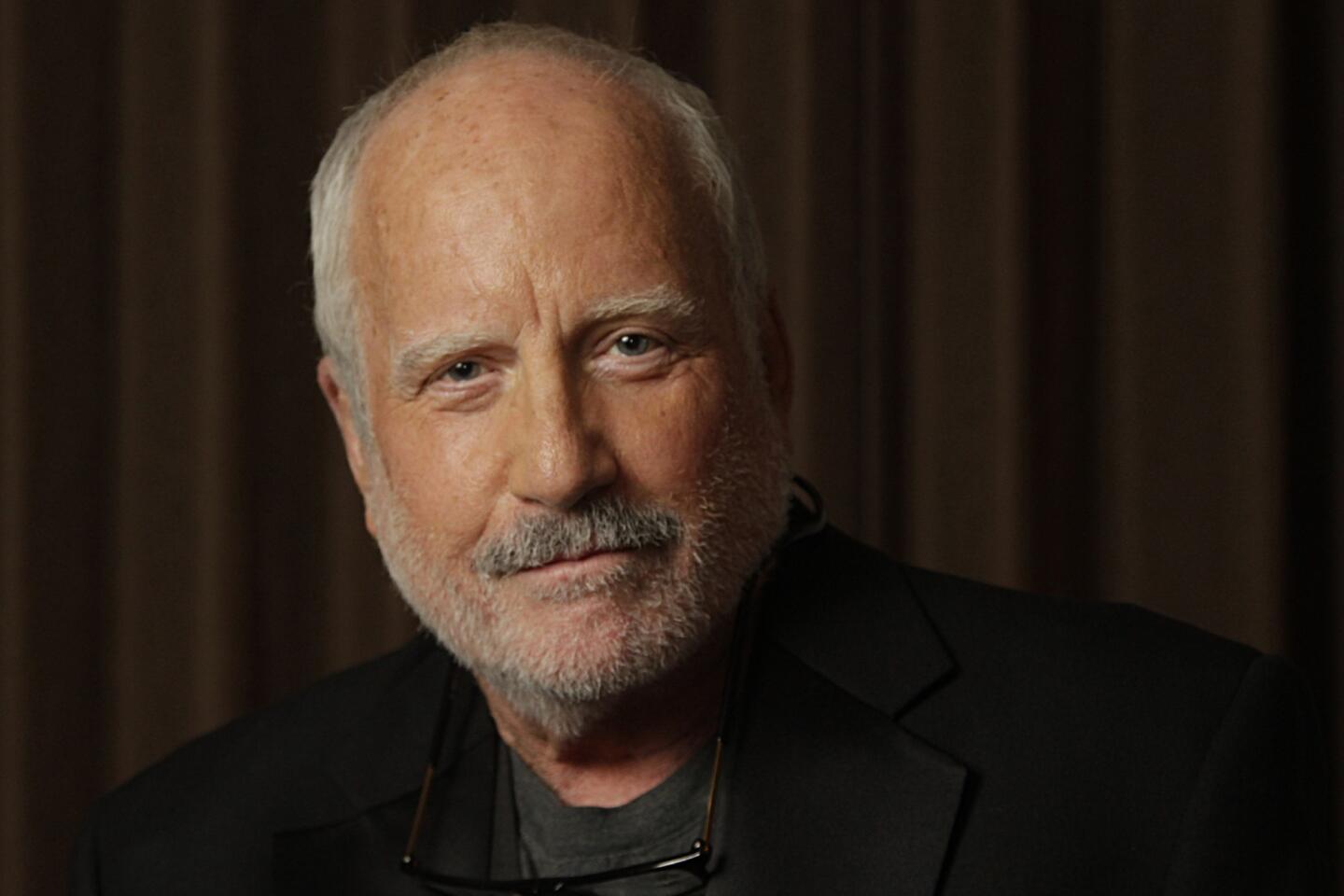

Richard Dreyfuss: A lesson in civics, and civility

Richard Dreyfuss has a lot on his mind. And he’s more than willing to share.

Among his talking points: the beleaguered state of civics education and filmmaking today — most roles in new films are “stupid,” he believes — studying at Oxford, directing John Gielgud and auditioning for Jack Nicholson’s 1971 drama “Drive, He Said.” He has a story about that one.

“I had gone out for one of the parts in ‘Drive’ and didn’t get it, and I was all grumpy,” said the 65-year-old Dreyfuss, who appeared trim and sprightly during a recent breakfast at a Brentwood hotel. “Then I went to see it. I see my character strip naked, go into a lab and take out scorpions, spiders and snakes and let them free. And then he runs full naked toward the camera.”

Dreyfuss’ blue eyes twinkled. “I said, I am so happy I didn’t do it.”

PHOTOS: Billion-dollar movie club

Of course, Dreyfuss went on to do many other movies, many of them legendary, including “American Graffiti,” in 1973, “Jaws” in 1975, “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” in 1977, “The Goodbye Girl” also in 1977 — which won him a lead actor Oscar — and 1995’s “Mr. Holland’s Opus,” which earned him a second Oscar nomination.

He’s been busy with his educational civic activities lately, so acting has been on idle for a while. But he’s back onscreen with the new techno-thriller, “Paranoia,” which opened Friday to poor reviews and even worse box office. He plays the father of lead actor Liam Hemsworth.

Hemsworth found Dreyfuss to be “one of the most interesting people I have ever met. He would come into the makeup trailer in the morning and he would just start talking to me about a certain topic, usually something I had no idea about. He would talk nonstop — he wouldn’t even take a break.”

“Paranoia” director Robert Luketic said he and others in the cast would relax and listen to Dreyfuss expound on his past.

“It was lovely to sit around and hear him talk about his wild days, his good days, his bad days, the directors he worked with, the people he’s loved,” Luketic said.

Dreyfuss’ role in “Paranoia” is small, but he turns it into something more memorable with his trademark cockiness, humor and warmth — he’s flirtatious around his nurse, loves to crack jokes and has a genuine concern for his son.

“He would kind of improv stuff,” said Hemsworth, who, at 23, knew Dreyfuss primarily from “Jaws.” “He would talk about the scenes beforehand and give me notes. It was never intrusive. He would always surprise me, like at the end of the movie when he puts his head on my shoulder. It is one of the most touching scenes in the movie. He’s one of the most in-the-moment, instinctive actors I have worked with.”

It was nearly a decade ago that Dreyfuss “retired” from film acting to pursue his first love — theater. “I am a very nice and good and decent and selfish person — I am an actor. I did it for 45 years, and anyone who does anything for 45 years has a right to stop.”

But the theater sort of bit back. Dreyfuss was fired that year from the London production of “The Producers.”

“I had a lot of issues,” he said. “I said, I don’t know how to sing or dance and they said, we don’t care. They cared.”

So he stayed in London. “I trolled for work. I lectured. I wrote articles in the Sunday Times,” said Dreyfuss, who now lives in San Diego with his third wife.

And he became a senior advisory researcher at Oxford for four years. “I attended classes and I started writing speeches. I would fly back and forth [from Britain to the United States] and give speeches. I have spoken to some 175,000 people all over the country.”

The speeches are in support of his nonprofit Dreyfuss Initiative, which he founded in 2006 to promote the teaching of civics in American schools.

PHOTOS: Hollywood backlot moments

“You can’t get the same answer from any educator about what is the goal of public education,” said Dreyfuss, who attended Beverly Hills High School and spent a year at Cal State Northridge.

“They just don’t know,” he said. “The goal of public education is pretty simple — to make children smarter on Tuesday than they were on Monday. I say if we don’t start teaching our children better we are going to lose our manufacturing industry, our commercial businesses. Our military is unreliable because we are in the grip of a paranoia about money. We don’t want to spend money on anything, including education.”

His interest in civics and American history isn’t a recent passion. When he was young, he memorized the speeches of famed attorney Clarence Darrow. And in 1987, he did the ABC special “Funny, You Don’t Look 200: A Constitutional Vaudeville.”

PHOTOS: Hollywood backlot moments

And it was the one and only time he got to work with his idol, Gielgud.

“I picked up the phone, called him and asked if he would play a member of the House of Lords deriding the Constitution. He said, ‘Yes, dear boy.’ So I wrote it, sent it to him and flew over to London. I got to the studio Monday morning and there is John Gielgud already dressed and lit. I said ‘action’ and he did it perfectly. I asked him to do it again and he did it perfectly. I changed the camera angle and he did it perfectly. I went up to him and said could you play it — I don’t remember the actual direction I gave him — and he patted my knee and said ‘How amusing, dear boy.’ Then he did it perfectly. We were done by 11 a.m.”

Dreyfuss admitted that he made a mistake using the word “retire” when he stepped away from film and TV work. “Frankly, I don’t know how else to make a living,” Dreyfuss said. “The only way I could make any money was to come back.”

Because he was out of the limelight, when he came back to work the roles weren’t as substantial. He’s done some movies — playing Dick Cheney in Oliver Stone’s 2008 “W” — guest shots on “Weeds,” “Parenthood” and A&E’s 2012 miniseries, “Coma.” And he’s worked in a few more films since “Paranoia.”

PHOTOS: Celebrities by The Times

“It’s been difficult because most of the roles are just so stupid,” he said. “I wouldn’t recommend to a young actor anymore to become an actor because I think the film industry has changed so terribly. The tools in the director’s tool kit used to be story, dialogue, character, and after that came cinematography and editing. Now it’s special effects, editing, and we are way down at the bottom part.”

Before he goes, Dreyfuss has another story to tell — about the first time he met Gielgud, when he was very young and very full of himself.

“I was 15 and a young prince in Hollywood then,” he said. “Everyone knew I was going to make it. We all heard that John Gielgud was coming to the Huntington Hartford to do ‘The Ages of Man.’ We all decided to go and make fun of him because he was an old has-been.”

But the unexpected happened.

“The man steps out from behind the curtains and opens his mouth. I bifurcated into two people. One of those people was Richard sitting with his friends in the balcony, and the other was in complete awe that the human voice could sound like that. I went backstage and shook his hand and said thank you. He changed my life. He changed my entire life.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.