Mastodon and the therapeutic power of the concept album

- Share via

Things are about to get very loud at Amoeba Records in Hollywood, where it’s a full house of head-bangers as the band Mastodon steps onto a small stage. The quartet immediately thunders into action with “Sultan’s Curse,” an onslaught of electric guitars and muscular beats.

The walls shake and a CD boxed set falls to the floor as lead guitarist Brent Hinds steps forward in tattoos and Viking red beard to sing: “Tired and lost/ No one to trust/ Who is there to give the push?”

The driving, breathless rock song is the opening track on the band’s just-released album, “Emperor of Sand,” which debuted at No. 7 on Billboard’s Top 200 albums chart, the fastest rise of the Atlanta rock group’s career. The 11-song concept album is Mastodon’s eighth and a further evolution of the band’s fusion of metal and prog-rock interests.

Its subject is illness and doom, with the album’s title character a kind of Grim Reaper of a desert wasteland, which stands as a metaphor for the struggle to survive cancer. For Mastodon, creating the intense, layered hard rock of “Emperor of Sand” has been a means of high-decibel escape and also a way of facing personal tragedy.

The album was made in 2016 during an ongoing period of darkness and grief following a breast cancer diagnosis for the wife of singer-bassist Troy Sanders. Singer-drummer Brann Dailor’s mother had been chronically ill for years. Then guitarist Bill Kelliher’s mother died of cancer during the writing sessions in Atlanta.

“Bill’s mom passed away in the middle of it,” recalls Dailor. “We were over at Bill’s house: Do you want to take the day off? ‘No, I want to go in the basement and play.’”

After 17 years, Mastodon has earned a reputation for its music of complexity and feeling. The rock quartet’s current tour (with Eagles of Death Metal) lands Thursday at the Hollywood Palladium.

Mastodon has long provided an outlet for dealing with personal crises.

“It’s a way to channel the anger and the grief and the sadness and every other emotion. It’s also a healthy distraction for a few minutes,” says Sanders, bearded with soaring eagles embroidered to his black western shirt. “When we entered the studio [that] October, my wife was bald, four tubes coming out of her chest, on her fifth or sixth surgery. The last place I wanted to be was anywhere except for home.”

To draw lyrical inspiration from a less-urgent part of their lives, Dailor says, would be “doing the music a disservice.”

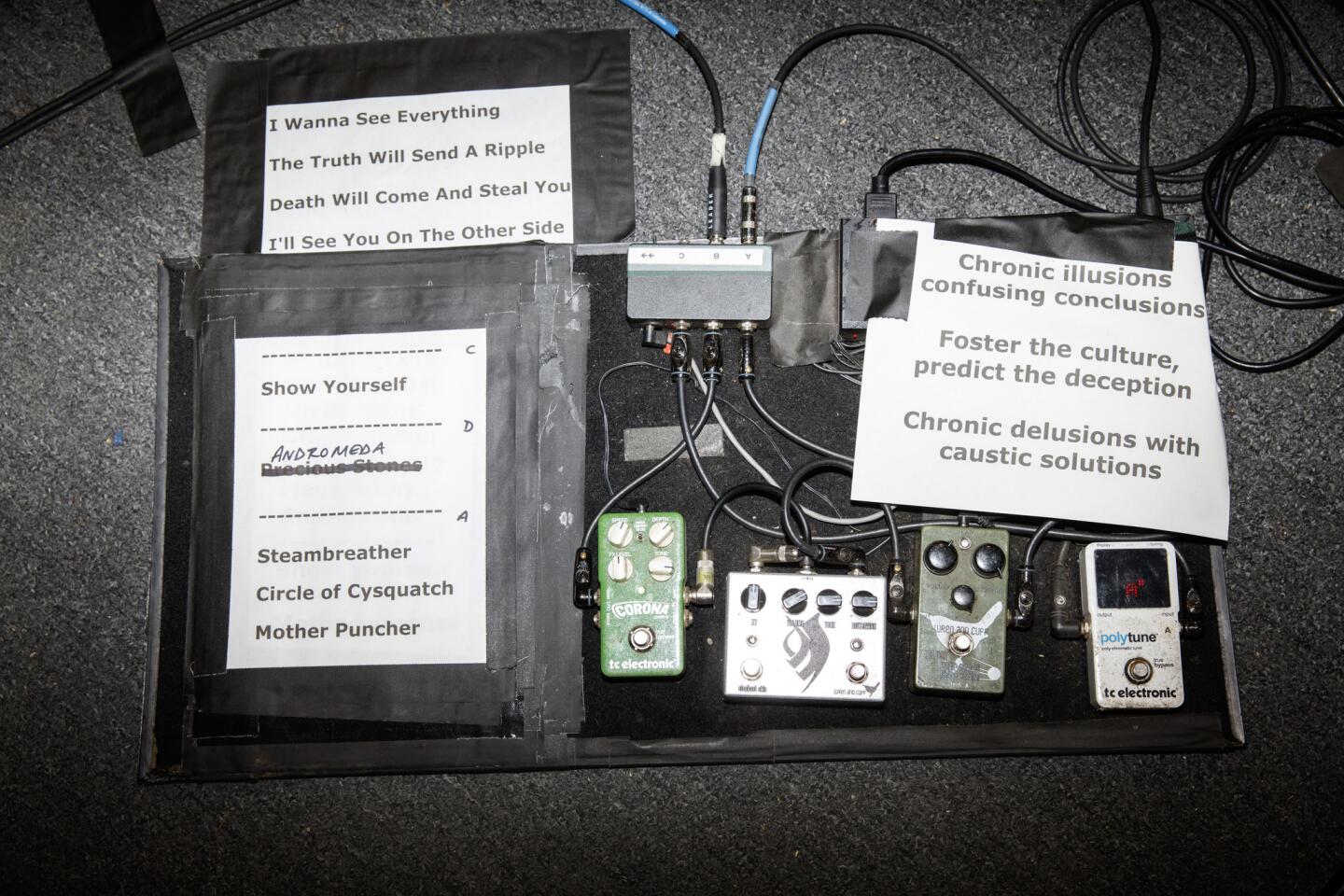

Not all the tracks were complex prog-metal eruptions with sweeping musical passages. One was “Show Yourself,” an unusually direct Mastodon song built from a straight-ahead rock riff from Kelliher. Dailor calls it “super-poppy” by Mastodon standards, while still dealing with the same themes of death and sadness.

It’s a “pleasant oasis within a dense album,” Dailor says. The song is the first single from “Emperor” and currently climbing the top-10 of Billboard’s mainstream rock chart.

Dailor’s concept for the music video was typically absurd, placing a group of bumbling Grim Reapers in a depressed work environment modeled after the 1992 movie drama “Glengarry Glen Ross.”

Elsewhere on the album, soaring musical passages offer a counterpoint to the lyrics. The track “Your Own Blood” begins with a moment of acoustic instruments before swirling into a Zeppelinesque epic.

“I think it’s a twist. We’re in control of that,” says Dailor, a winged wolf in flight on his black T-shirt. “To write these fantastical versions of these stories gives you the opportunity to flip it and create this mythology that is more soaring and triumphant. You’ve conquered it.”

Brann was first introduced to the idea of music as a setting for larger themes while hearing Mozart’s Requiem as a child. The classical piece still resonates.

“Now, when I hear those first notes of Requiem, I feel this boiling of emotion start to come to the surface,” he says. “We try to look for that for ourselves in the music we are writing together. One of the things that has kept us together as a band for this long is having those emotional moments in the practice space with each other.”

Mastodon albums began to grow deeper thematically and more personal with another concept album, 2009’s “Crack the Skye,” which dealt in part with the death of Dailor’s teenage sister. “We were like, ‘Oh, we’re that band.’ For me personally, there are some lyrics that will transport me to where I don’t really want to go, but it takes me there. You keep doing that to yourself, but I think it’s healthy.”

The new album was recorded during three weeks of sessions near their Atlanta home base at the Quarry in Kennesaw, Ga., followed by another several days of overdubs, vocals and mixing at Henson Studios in Los Angeles. Mastodon worked again with producer Brendan O’Brien, their collaborator on “Skye.”

During sessions for that earlier recording, O’Brien eased band members toward taking themselves as vocalists more seriously. Until then, Mastodon was a band of players where singing was a reluctant but necessary afterthought.

After drum tracks are recorded, the bulk of lyric writing typically falls to Dailor. After “Skye,” the band began to receive lengthy letters responding the human stories within the lyrics.

“We met a lot of people who were extremely touched by this,” says Sanders. “We started hearing from all sorts of people about how the albums helped them, and we’re like: ‘Wow, we’re helping people.’ That’s not like something we saw for us. We like that.”

For “Emperor of Sand,” the band drew not only on personal experience but a stockpile of riffs Kelliher had created while on tour. He then joined Dailor to begin developing songs for the album.

“Both of us were going through sick mothers and illness in the families,” Kelliher says. “I’ve got thousands of riffs in my head. When I can get some of them out of my head, it’s like a demon being exorcised.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.