How Mike Shinoda found life after the death of Linkin Park’s Chester Bennington

- Share via

Mike Shinoda’s wife used to joke that his tear ducts were broken.

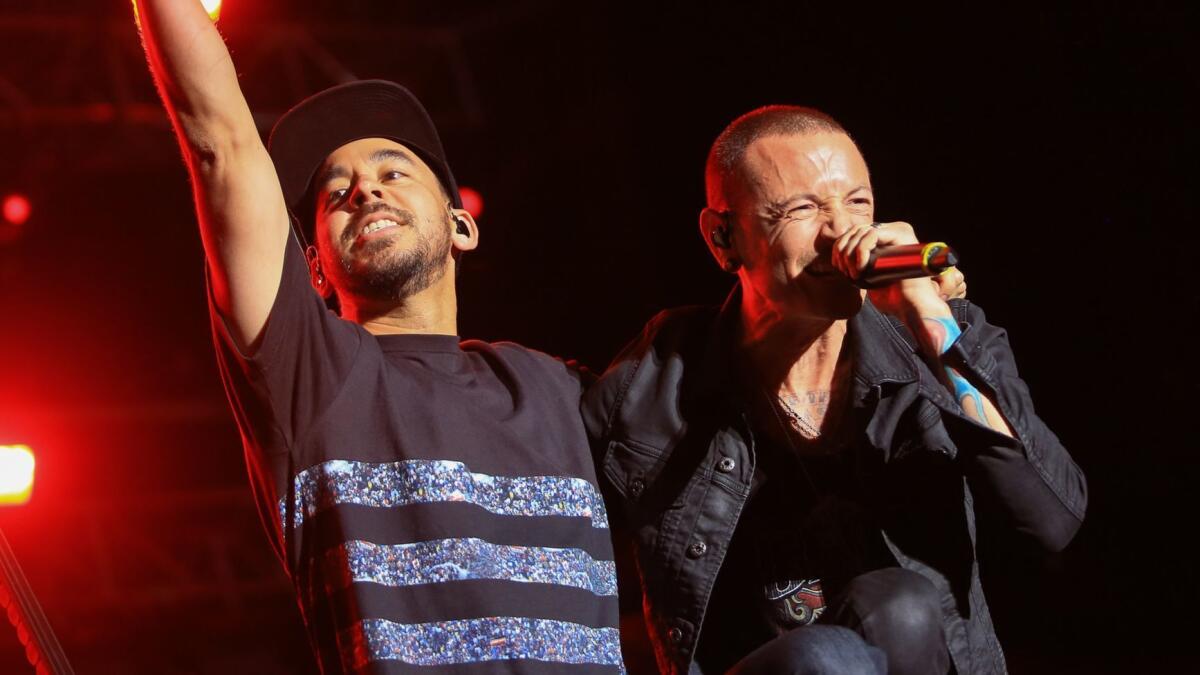

As the painstaking sonic mastermind of Linkin Park, this Southern California native spent years creating carefully detailed tracks — dense with serrated guitars and throbbing hip-hop beats — that showcased the signature wail of the group’s talented but troubled frontman, Chester Bennington.

Shinoda did more than program and produce; he rapped too, and with plenty of aggression to match the band’s forceful attack. Even at his most intense, though, Shinoda as a vocalist always put across something of an intellectual quality — outraged but not agonized.

“By nature I’m very analytical,” he acknowledged on a recent afternoon. “So even if I’m going to talk about something that’s really emotional, I’ll communicate it in a way that’s organized.

“Maybe it’s because I’m half Japanese and was raised with that Japanese approach to things,” he added, then laughed quietly. “I’m sure there’s a Japanese word for it that I’m forgetting.”

With his new solo album, “Post Traumatic,” Shinoda is revealing a different side of himself — although, as that title suggests, not necessarily by choice.

Due June 15 from Warner Bros. Records, “Post Traumatic” chronicles the bruising aftermath of Bennington’s death in July of 2017. The singer, who was 41, was found having hanged himself in his home in Palos Verdes Estates just a week before Linkin Park was set to begin a North American tour.

Shinoda’s songs address the tragedy head-on. The rawness of his grief can be startling, as in the album’s opener, “Place to Start,” in which he describes “feeling like every next step’s hopeless” in a voice just above a whisper. In “Nothing Makes Sense Anymore” he’s “a shadow in the dark trying to put it back together as I watch it fall apart.”

Then there’s “Over Again,” a mournful hip-hop cut that vividly recounts Shinoda’s complicated thinking about a tribute concert Linkin Park played in Bennington’s memory last October at the Hollywood Bowl — the band’s only public performance, at least so far, without its beloved frontman.

“I think about not doing it the same way as before,” Shinoda raps, his anxiety clearly audible, “And it makes me want to puke my … guts out on the floor.” There’s nothing cerebral about the lyric, which includes an unprintable expletive; it’s purely the sound of a man coming to terms with his vulnerability.

“This is really a different record for Mike,” said Chino Moreno of Deftones, a longtime friend who appears on “Post Traumatic,” which emphasizes electronics over guitars and features additional cameos by Machine Gun Kelly and Blackbear. Moreno said he was “blown away” in particular by the immediacy of “Over Again.”

“My man wrote a verse before he went to that show and then wrote the second verse after he got back from the show,” he said. “It’s just this visceral reaction in real time.”

Shinoda needed to take a minute before he could be so immediate.

“Eleven months ago I was a mess,” he said of the days after Bennington died. “I mean, I wasn’t leaving my house.” Seated on a sofa at his label’s offices in Burbank, Shinoda, 41, was characteristically methodical in his recollection of a moment that “just felt like chaos,” as he put it.

“I couldn’t hold on to the idea of what I wanted, even with simple things, for long enough to do anything about it,” he said.

After a week or so, he went out to lunch with his wife, Anna. “I was, like, ‘This is nice,’” he remembered. “And on the way back to the car we got trapped by two paparazzi. They were so gross, snapping pictures and asking me about Chester. I got home and was, like, ‘That’s exactly why I didn’t leave. I’m not going out again.’”

Ensconced at his home, where he and Anna live with their two young children, Shinoda started painting and eventually “got up the courage to play some music — just to try and calm down and put a foundation under my feet that I could trust.”

Moreno, whose Deftones bandmate Chi Cheng died in 2013, said he told Shinoda how much he’d been helped at that time by “burying [his] head in creativity.”

“You have maybe a little bit of guilt about doing it,” Moreno said. “You’re uncertain if it’s OK to be creative. But music is a comfort — it’s like a blanket for me. And I know it is for Mike too.

“We talked a lot about letting it happen and not feeling bad about it.”

As he began writing songs, Shinoda’s goal was simply to document “this truth that exists in the world that you’re feeling today and that you might not feel tomorrow.” For the first time, he wasn’t worried about the kind of beats or textures that defined Linkin Park’s music, or even the shapely melodies; he allowed himself to follow his unpredictable emotions wherever they took him.

“There were definitely times when I’d listen back and be, like, ‘I sound crazy,’” he said. “But maybe that’s because I was a little crazy.

“Last year for me was like the nuclear bomb of loss of control,” he continued. “I have a body of work, a legacy that I have a feeling of pride about, and then I felt like it was ruined.

“I had to look at that and say, ‘Well, I can’t do anything about what happened.’ All I could do is say, ‘What’s next?’”

In its finished form “Post Traumatic” has some of the polish Shinoda famously brought to Linkin Park (and to a 2005 album he released under the name Fort Minor). The bleary “About You,” for instance, demonstrates how closely Shinoda has been paying attention to recent trends in hip-hop production.

But Warner Bros. chief Tom Corson isn’t wrong when he says the album shares something with the radically naturalistic documentary style known as cinéma vérité; it puts listeners right in the room with Shinoda as he grapples with the reality of Bennington’s death.

“I’ve always listened to dark music — Depeche Mode, Public Enemy, Nine Inch Nails — but hadn’t really experienced the things that were going on in the songs,” Shinoda said. Even in Linkin Park, he was writing from a different perspective than his late bandmate was.

“I wasn’t a teenage drug addict,” said Shinoda, who grew up in Agoura Hills and studied illustration at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena. “I wasn’t running around in the streets trying to scrape together money to buy whatever the hell it was he was buying at the time.

“But now I’m in this horrible situation,” he said. “I’m a member of this club that I never asked to be a part of.”

Shinoda isn’t alone. There are Linkin Park’s other members, of course, with whom he said he remains close. Just the other day he saw bassist David Farrell, known as Phoenix, and asked if he could devise a fake job for Farrell that would allow the bassist to go on the road with him. (Shinoda has Asian and European festival dates scheduled this summer behind “Post Traumatic”; before that, he’ll perform June 14 at Amoeba Music in Hollywood.)

Asked about Linkin Park’s future — if indeed the band has a future — Shinoda sighed.

“Whenever I say anything with regards to our plans, it turns into a clickbait headline,” he said. “But my gut is that I want it to work out. I’ll be looking for ways for it to work out.”

In a sense, the club also includes Linkin Park’s devoted fans, many of whom are no doubt looking to Shinoda’s album in the hopes that it might articulate their own grief over Bennington’s death.

Shinoda said he’s aware of that responsibility. Having talked with thousands of fans over the years about their struggles with depression or addiction, he knows how seriously they take the band’s music.

His experience with Bennington, though, has changed his understanding of the role he plays.

“Look, anyone would do anything we could to help somebody,” he said. “But really it’s up to you. You have to be the one to decide to do something about it, because nobody else can be with you 24-7. And that’s one of the tougher things about this whole thing.

“There’s no human that could’ve been there like that for Chester. At the end of the day, it was his decision or not. And the same goes for the fans.

“I don’t look at this as an inspirational record,” he went on. “I’m not going to go out and save a bunch of people. My intention is just to go out there and tell my story.”

Twitter: @mikaelwood

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.