Infrasonic Sound presses forward with cutting vinyl masters

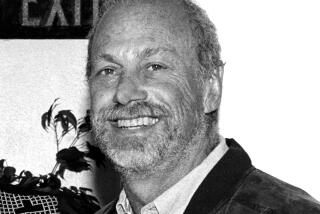

The scariest day of Pete Lyman’s life was the morning the movers came for his 1978 Scully LS-76 vinyl-cutting lathe. It’s one of two rare machines at Lyman’s company, Infrasonic Sound, which cut the final mastered versions of vinyl records for acts like Radiohead, Ben Harper, Best Coast and No Age. The machine, which looks like a vintage Bond villain torture device, is susceptible to breakdowns in careless hands.

When the team of piano movers began to schlep it up the stairs to Infrasonic’s new Echo Park offices in April, Lyman had to look away.

“I just couldn’t watch,” he said. “One guy had a strap tied to his neck as they pulled it up. But they said not to worry, they’d done way bigger jobs than this.”

Amid the ongoing revival of vinyl records — a small rebuttal to the slow death of physical album sales — the esoteric craft of mastering and cutting vinyl lacquers is becoming ever more essential.

American sales of vinyl records grew 36% in 2011, for a SoundScan total of 3.9 million albums. Lyman says that vinyl makes up 60% of Infrasonic’s mastering jobs, and that his vinyl work has grown 230% over the last five years — 40% in the last year alone.

Lyman got his start in production while playing in punk bands and producing for friends, and he co-founded Infrasonic in 2004. An early break came when No Age booked him to help on a series of EPs that led to their deal with Sub Pop, and Lyman worked on each of their subsequent records.

“It was the first time I understood that mastering can make songs that sound good and raw, sound great,” said Dean Spunt, No Age’s singer-drummer and owner of the vinyl-heavy label Post Present Medium.

After years of mastering and producing simultaneously, Lyman eventually realized that mastering was less stressful and just as fulfilling for him.

“I appreciate being the last person in the chain, when most of the fighting and bad stuff about making a record is out of the way,” he said.

The mastering is a last chance to perfect the volume and sound of a master recording that’s later pressed out as a vinyl record or digital album (the process is different for each format). Infrasonic handles both for major-label and indie clients alike.

But facilities like Infrasonic that also can cut the master lacquer discs for duplication are rarer — only about a half-dozen exist in Southern California, one of America’s hubs for record-making. Almost all the machinery needed to do so is decades old (Infrasonic’s other lathe, a Neumann AM-32, dates back to 1956) and the repair techs who know these units are quite literally dying off.

Infrasonic’s move into a prominent 4,000-square-foot Sunset Boulevard location expands its capacity for both processes. As the vinyl format returns as a necessary part of a band’s commercial output, Infrasonic wants to demystify this crucial step in making records.

“We want to educate people about what vinyl’s supposed to sound like,” Lyman said. “You can’t skimp on this last part of the process. It’s your art.”

Infrasonic has a full-service recording studio in another facility (Beck and the Mars Volta have recorded and mastered there), and the mastering shop’s three full-time engineers — including Jeff Ehrenberg and Grammy winner John Greenham — have full slates of digital mastering work as well.

But the shop’s growing specialty is mastering and cutting 7-, 10- and 12-inch vinyl records. Though they often tackle digital and vinyl mastering for the same release, mastering vinyl is a distinct task from digital mastering, as vinyl has limitations at certain sound frequencies that require specific tweaks to a recording.

Small but growing sales figures undersell the available work for a shop like Infrasonic — even a 7-inch single that sells 10 copies needs a lacquer to press it, and Infrasonic’s setup can also cut lacquers from recordings mastered at other studios. Lyman has participated in panels on vinyl-cutting and mastering at industry events at South by Southwest and the Grammy Museum.

As the medium’s potential grows, however, the sheer age, rarity and complexity of the machinery needed to produce LPs is an ongoing obstacle. It can cost tens of thousands of dollars to buy and properly set up a professional-grade cutting lathe, and many replacement parts are discontinued and need to be fabricated from scratch or bought at a premium. Lyman jokes about taking out a life insurance policy on Infrasonic’s shamanistic repairman, the Culver City-based Len Horowitz.

Many respected independent mastering engineers, like Dave Cooley’s Elysian Masters, work in Southern California. But of the half-dozen lacquer-cutting shops here, including Golden Mastering in Ventura and Erika Records in Buena Park, Infrasonic’s size, scope and the new office’s proximity to the L.A. music business leave it well-positioned to lead in this necessary corner of the vinyl revival.

As recorded music grows more ephemeral and digital, and artists are capable of producing and mixing in home studios, the hair-pulling aspects of mastering and cutting quality vinyl are a reminder that an LP is an artifact. It takes a kind of alchemy to forge it from sound waves and raw plastic.

“I sold my house and moved into an actual closet, like in someone’s bedroom, to build my first studio,” Lyman said. “In a way, my whole life revolves around vinyl records. I still remember playing in punk bands and pressing my first 7-inch. It was the coolest thing.”

ALSO:

Metal label Century Media reverses anti-Spotify stance

Early recordings by Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee discovered

‘Dark Knight’s’ Hans Zimmer writes ‘Aurora’ to benefit Colorado victims

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.