TV review: ‘George Harrison: Living in the Material World’

- Share via

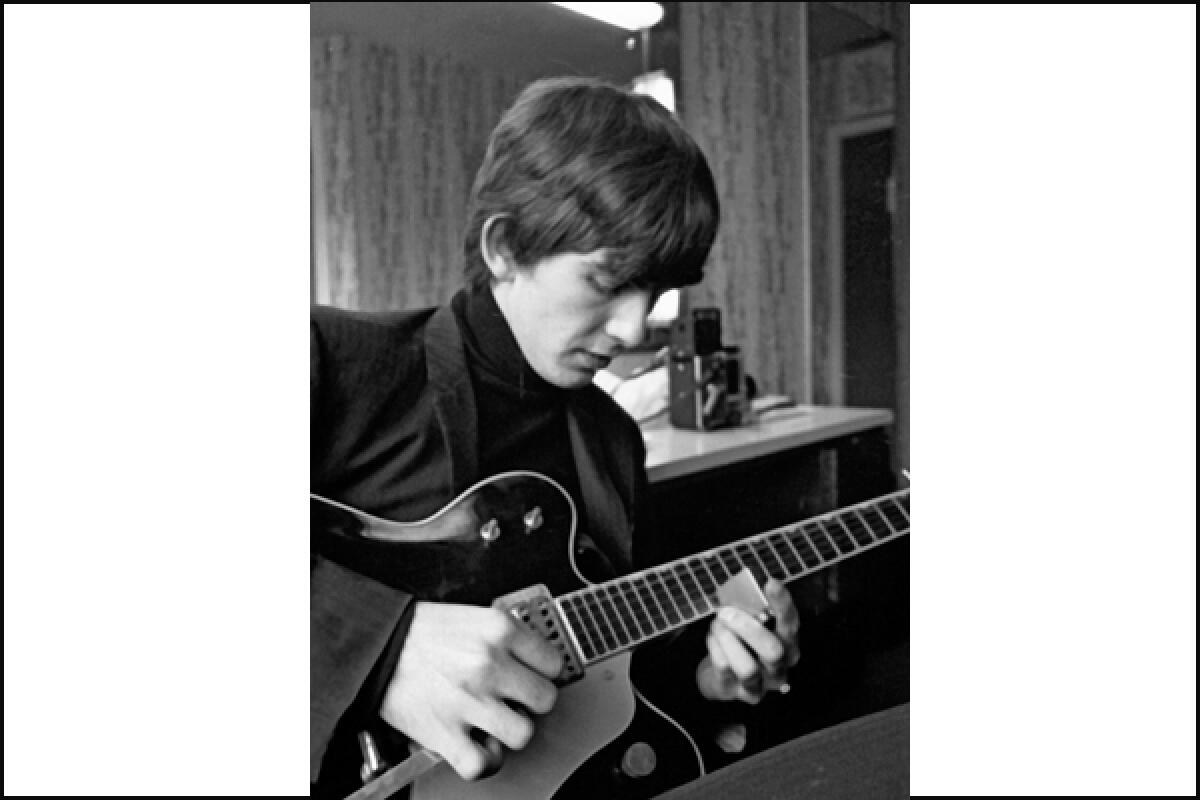

“George Harrison: Living in the Material World,” which premieres Wednesday and Thursday on HBO, is a long, lovely meditation on the Beatle sometimes called the Quiet One and the quiet one sometimes called a Beatle. Directed by Martin Scorsese at the invitation of widow Olivia Harrison, it is not especially informative in the way documentaries usually strive to be, a cataloging of causes and effects and significant facts and figures; nor has it been made as a brief for George’s unsung genius. In fact, it leaves a lot out and doesn’t always explain what it puts in. But it is not really so much a film about a career as it is about a life and not so much about a life of events as of spiritual progress — a portrait of character more than of “a character.”

Any new Beatles-related documentary is going to need to find a different way through familiar material, a way made more difficult by the group’s own enormous 1995 “Anthology” (more than 11 hours in the DVD cut). Certainly some well-trod ground is trod here again, but Scorsese generally stays off the beaten path. Coming 10 years after Harrison’s death from cancer at 58, “Living in the Material World” draws heavily on the singer’s own collection of photographs, films, recordings and documents. There are letters read by his son, Dhani (“Don’t think I’ve gone off my rocker because I haven’t,” he wrote home from India), self-portraits in a fisheye lens, a tape of his first sitar lesson with Ravi Shankar — “the first person to impress me,” among the impressive people the Beatles met, “because he didn’t try to impress me.”

Broadly speaking, it’s Scorsese’s follow-up to “No Direction Home,” his 2005 PBS film about Bob Dylan, also made to run over two nights. This may be the better work, for its depth of feeling and its relatively more forthcoming and knowable subject. Scorsese, with editor David Tedeschi (who also cut the Dylan documentary), arranges his elements musically, beginning and ending with an image of George playing peek-a-boo behind a bed of tulips, as voices speak of his death, his absence and his presence-in-absence. The rhythms of the film seem to be purposely abrupt, cutting in and out of songs and between scenes of sound and silence, pressure and release, public and private space, as if to underscore Harrison’s own dual nature, much remarked upon here. (Ringo Starr notes his “love, bag-of-beads personality and also the bag of anger.”)

We see George as the meditating Beatle, the skeptical Beatle, the movie-producing ex-Beatle, the ex-Beatle whose first wife, Patti Boyd, leaves him for Eric Clapton. (Clapton and Boyd have radically different memories of this episode.) We hear from the expected quarters (Paul McCartney, overestimating the world’s underestimation of George and Ringo; Ringo, his usual sweet self), the less expected (a pre-incarcerated Phil Spector, looking like something out of David Lynch) and the unexpected (Jackie Stewart, the race-car driver). We see him, distressingly close-up, on a 1974 solo tour, during which he sounded bad and looked worse, and learn that there were times when he did a lot of cocaine and slept with women not his wife. Having got a whiff of this, the National Enquirer declared, “Shocking new doc rips the lid off the Quiet Beatle.” But that is hardly the effect of this film — a love letter, warts and all.

The youngest of the Fab Four — a “cocky little guy,” as McCartney recalls him in their shared school days — but perhaps the oldest soul, George was only 27 when the group split up. His early death notwithstanding, he had a lot of living to do, and though it accounts only for the last third of the film, it’s where the drama subtly starts to gather. Olivia Harrison narrates, in terrifying detail, the 1999 in-home attack that left her husband with multiple knife wounds and a collapsed lung.

But light and dark alternate until the end, with light getting the last word. His last records are among his best, and life in the end came down to ukuleles and gardening, the sky and sea, and an evidently satisfying sense of his own temporality. (Scorsese’s film, which takes its name from one Harrison song, might as easily have taken it from another: “All Things Must Pass.”) Which, all this considered, is nice work if you can get it, in the immaterial material world.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.