Boiling Point: Tech companies clam up about AI’s climate costs

Welcome to Boiling Point. I’m Hayley Smith, a reporter on The Times’ climate team filling in for my colleague Sammy Roth.

Artificial intelligence technology is guzzling water and energy in California and around the globe, yet most tech companies have not been forthcoming about the actual environmental costs of their applications, my colleague Melody Petersen reports.

That’s a huge problem, as their energy and water consumption will undoubtedly strain supplies and drive up demand for climate-warming oil, gas and coal — all while leaving users in the dark about their true contributions.

By some estimates, ChatGPT uses about 16 ounces of water for as little as 10 queries, while AI-generated answers from Google use up to 8.9 watt-hours of electricity per request, Petersen reported. But when she pressed for details, both companies clammed up.

Google, which has already acknowledged that its investments in AI could keep it from reaching its net zero goals, didn’t respond to her request for comment. Earlier this year, the company rolled out Google AI Overview, a feature that provides short AI-generated answers in response to searches, which users currently can’t opt out of.

OpenAI, the company that created ChatGPT, declined to answer Petersen’s specific questions but said it was “constantly working to improve efficiencies.”

In light of all that secrecy, I thought I might try to go straight to the source: I asked ChatGPT about its own environmental impact. I expected an answer along the lines of what Hal 9000 says after it turns to the dark side in 2001: A Space Odyssey: “I’m sorry Dave — I’m afraid I can’t do that.”

But its response was surprisingly helpful. The tool noted that “the environmental impact of ChatGPT, like other large-scale AI models, encompasses several factors related to its development, operation, and data center infrastructure.”

It went on to tell me that the largest amount of water and energy used by AI models occurs during the training phase, which can burn through substantial megawatt-hours of energy and hundreds of thousands of liters of water per hour.

Running a search is less demanding but still contributes to the overall cost, the robot said, adding that “the impact per query is likely quite small, but it’s part of a broader environmental footprint associated with running large-scale AI systems.”

When asked for specifics, ChatGPT said the exact amount of water used for a single query “isn’t straightforward to calculate directly,” and that it depends on the efficiency of the data center’s cooling systems, among other factors. It gave a similar answer for the amount of energy per query, but cited a study that estimated a single search can use about 0.3 to 0.6 kilowatt-hours of energy.

I posed similar questions to Google, asking it, “What is the environmental footprint of Google’s AI Overview search?” and, “How much energy and water does Google’s AI Overview use?” Ironically, it didn’t provide AI Overview answers to either of those questions.

However, a July report showed the company’s carbon emissions have increased 48% since 2019 and 13% since last year, Petersen wrote.

What’s more, ChatGPT tried to reassure me that it is hard at work on a solution — and that many tech companies are investing in renewable energy sources, hardware upgrades and carbon offset projects to balance out their emissions.

“In summary, while ChatGPT and similar models do have an environmental impact, ongoing efforts in technology and sustainability are aimed at reducing this footprint,” it said. “The tech industry is actively working on improving efficiency and increasing the use of renewable energy to lessen the overall impact.”

Whatever you say, Hal.

Now here’s a look at more climate coverage in California and around the West.

TOP STORIES

California’s aging Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant is drawing renewed criticism from experts who say the facility is too costly — and too dangerous — to continue operating. The plant carries a roughly 1 in 25,000 chance of suffering a catastrophe before its scheduled decommissioning in just five years, in part because of its proximity to nearby earthquake fault lines. My colleague Noah Haggerty has the latest.

On the heels of California’s hottest month ever, a new study published in the medical journal JAMA confirms that heat-related mortality is on the rise in the United States. The study, which analyzed death certificate data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, found that high temperatures have contributed to the deaths of more than 21,500 Americans since 1999 — with a notable uptick in the last seven years. State and federal officials said they are taking action to address the rising threat, but heat continues to be the deadliest of all climate hazards in the U.S. Here’s my story.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

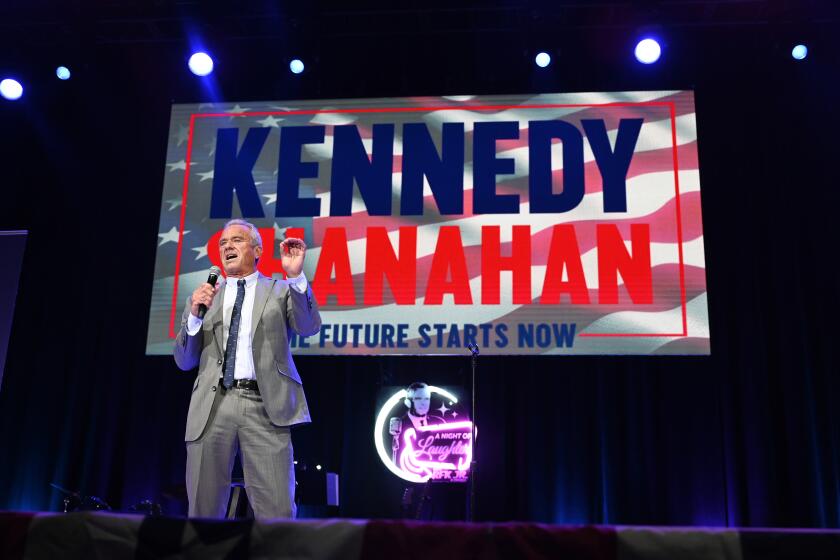

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. came from green roots — spending decades as an environmental lawyer and founding a global organization that fought for clean water. That’s why his withdrawal from the 2024 presidential election and subsequent support of former President Trump has left some environmentalists and long-time colleagues disappointed and dismayed, Melody Petersen reports. Trump, who has called climate change a “hoax,” worked to overturn numerous environmental rules during his administration.

State lawmakers are vowing to do more to enforce outdoor heat protection laws in the wake of an investigation by the Los Angeles Times and Capital & Main. The investigation found that field inspections by the California Division of Occupational Safety and Health, or Cal/OSHA, dropped by nearly 30% between 2017 and 2023, even as global temperatures continued to rise. Legislators told investigative reporter Robert J. Lopez they were “disappointed” and “infuriated” by the findings, and said they will push for new rules to protect employees.

AROUND THE WEST

Crews are making progress on a massive $92-million wildlife crossing over the 101 Freeway in Los Angeles, which will provide crucial habitat connections and safe passage for the region’s threatened mountain lions and other species. But the project has at least one other benefit: It has inspired officials to replicate it across California. My colleague Lila Seidman wrote about the launch of a new initiative called California Wildlife Reconnected that will leverage public and private resources to implement a statewide plan for wildlife connectivity.

Conditions have gone from bad to worse for residents of Rancho Palos Verdes, who continue to face unprecedented challenges from relentless land movement in the area. Exploratory drilling in the Palos Verdes Peninsula city has confirmed that the landslide is stemming from a deeper slip plane than previously thought, which has only exacerbated the sense of urgency for residents dealing with dangerous cracks, shifting floors, gas shutoffs and other existential threats to their homes, my colleague Grace Toohey reports.

Long-awaited plans to upgrade and repair an aging, federal wastewater treatment plant at the U.S.-Mexico border are underway to help slow the billions of gallons of untreated sewage and industrial waste that pour into San Diego County from Tijuana each year. The U.S. International Boundary and Water Commission announced that funding has been awarded to begin the crucial repair work at the plant. However, the project could take years to complete, Tammy Murga with the San Diego Union-Tribune reports.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

Environmental groups are fuming after a major oil and gas company was exempted from a state law designed to help plug depleted and barren oil and gas wells. The merger of California Resources Corp. and Aera Energy made CRC the largest oil and gas producer in the state — yet the Department of Conservation’s Geologic Energy Management Division, ruled that the stock-transfer nature of the deal saved it from having to abide by the state’s Orphan Wells Prevention Act, my colleague Tony Briscoe reports. California is home to roughly 100,000 unplugged oil wells.

Speaking of oil, Gov. Gavin Newsom backtracked on a controversial plan to extend deadlines for oil and gas companies to monitor oil wells for leaks near homes and schools. However, his administration also eliminated from the budget bill any funding to implement the law, Julie Cart of Cal Matters reports.

The nation’s first zero-emissions passenger train rolled into San Bernardino earlier this month. The $20-million, 108-passenger train known as the Zero Emission Multiple Unit, or ZEMU, is North America’s first self-powered, zero-emission passenger train to meet Federal Railroad Administration requirements. Passengers should be able to ride the clean-energy line early next year, my colleague Andrew Campa reports.

ONE MORE THING

A summer marked by extreme weather can now claim yet another anomaly for the Golden State: snow in August.

An unusually cold weather system from the Gulf of Alaska dropped fresh powder in parts of the Sierra Nevada over the weekend and closed portions of Highway 89, the San Francisco Chronicle reported. A spokesperson for the Palisades Tahoe resort told the paper it is “exceptionally rare” for the area to see snowfall in August, which is typically one of its warmest times of year.

The Tahoe ski season ended just three months ago.

We’ll be back in your inbox Thursday. To view this newsletter in your Web browser, click here. For more climate and environment news, follow @whereishayley and @Sammy_Roth on X.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.