A clean energy breakthrough could be buried deep beneath rural Utah

- Share via

DELTA, Utah — If you know anything about solar and wind farms, you know they’re good at generating electricity when the sun is shining or the wind is blowing, and not so good at other times.

Batteries can pick up the slack for a few hours. But they’re less useful when the sun and wind disappear for days at a time — a problem the Germans call “dunkelflaute,” meaning “dark doldrums.”

Those long stretches of still, cloudy days are one of the main obstacles standing in the way of renewable energy fully replacing fossil fuels.

For Los Angeles, salt may be a solution.

One hundred miles south of Salt Lake City, a giant mound of salt reaches thousands of feet down into the Earth. It’s thick, relatively pure and buried deep, making it one of the best resources of its kind in the American West.

Two companies want to tap the salt dome for compressed air energy storage, an old but rarely used technology that can store large amounts of power.

It would work like a giant battery. Hollow caverns carved out of the salt — each more than 1,000 feet from top to bottom and several hundred feet wide — would be pumped full of air at high pressure, using energy generated by solar panels or wind turbines during times when the power isn’t needed. Like storing wind (or sun) in a bottle.

When the power is eventually needed, the tightly packed air would be released from the caverns, turning turbines on the way out to generate electricity.

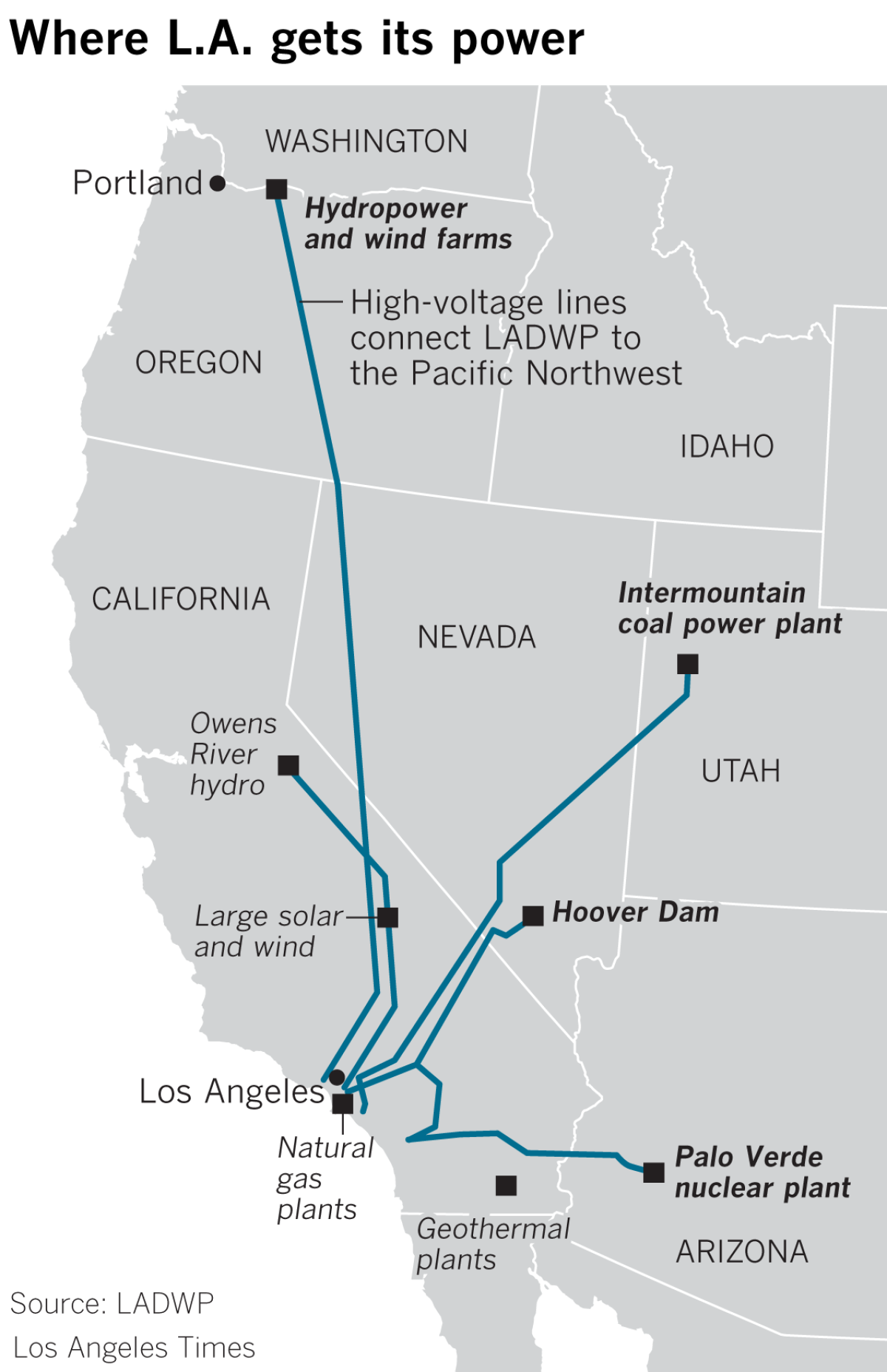

The electricity would be ferried to Southern California through a 488-mile transmission line, built in the 1980s to transmit energy from Intermountain Power Plant, which is now the last coal-fired generating station serving California. The coal plant is scheduled to shut down in 2025.

L.A. will build a gas-fired power plant in Utah, even as Mayor Eric Garcetti touts a “Green New Deal” to fight climate change.

The salt dome’s proximity to Intermountain — they’re literally across the street from each other — is a lucky coincidence.

“It’s extraordinarily rare to have geology, transmission and a coal plant all sitting right next to each other,” said Jeff Meyer, president of Range Energy Storage Systems. “You ought to take advantage of this, because all the stars have lined up.”

It’s not all rosy: Compressed air storage technology requires the burning of natural gas, a planet-warming fossil fuel.

The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, which hopes to tap the salt dome for energy storage, also plans to build a gas-fired power plant at Intermountain to help replace the coal facility. Clean energy advocates say the gas plant is unnecessary and incompatible with Mayor Eric Garcetti’s agenda to fight climate change.

A new, old type of energy storage

Compressed air energy storage has been used for decades, but only at two facilities in Germany and Alabama, built before solar and wind started creating challenges for power grid operators.

“This is a pretty simple concept,” said Bobby Bailie, director of business development for energy storage at the German industrial firm Siemens. “You’re pushing air into a cavern, storing that energy. And at times when you need it, you pull it back out.”

High-quality salt domes are relatively rare in the American West, although they’re common along the Gulf Coast, where many are used to store oil.

The Utah salt dome was discovered in the 1970s by drillers looking for oil and gas. It’s roughly three miles wide and a mile from top to bottom. It starts about 2,500 feet below the ground and stretches down to 7,500 feet — an ideal depth for pressurized caverns.

Two companies hope to tap the salt for energy storage.

One is Magnum Development, which is backed by the Houston-based private equity fund Haddington Ventures. Magnum has already built several hollow caverns in the salt dome by drilling wells, pumping in water to dissolve the salt, and pumping out the resulting brine. The caverns are used to store butane and propane.

The other company is Range Energy Storage Systems. It’s a partnership between North Carolina-based electricity giant Duke Energy, Sammons Enterprises of Dallas and American Transmission Co., whose headquarters is in Wisconsin.

Magnum and Range both submitted proposals to Southern California Public Power Authority, a consortium of public power agencies whose members include Los Angeles and 10 other cities. SCPPA officials are currently negotiating with one of the companies, although they won’t say which one.

Compressed air would provide the most value on an electric grid dominated by solar, wind and hydropower. Although lithium-ion batteries can store a few hours’ worth of energy — making them ideal for keeping the lights on at night, after the sun goes down — they’re far too expensive for banking large amounts of electricity for those rare occasions, typically during winter, when the sun and wind go into hiding for several days, grid experts say.

And that’s not likely to change, even as lithium-ion technology keeps getting cheaper.

“You’re never going to build enough batteries to get yourself through a week of low wind and sun, because you’re using those batteries once a year, but you’re paying full price for them,” said Matthias Fripp, an electrical engineering professor at the University of Hawaii. “They’re going to cost 365 times as much as those batteries you use every day.”

Hydrogen and heartache

Magnum co-founder Rob Webster says the Utah salt dome can probably fit around 100 caverns, meaning it could be used by utilities across the West.

“This is very much a regional play,” Webster said. “It can really accelerate the transition to 100% renewables.”

Still, the technology has downsides.

For one thing, compressed air is limited by geography, meaning it probably won’t play a leading role in cleaning up the power grid nationally. Other energy-banking technologies could provide much larger amounts of long-duration storage if they achieve commercial viability.

Compressed air systems also require the burning of natural gas — a fossil fuel — to heat the air as it leaves a storage cavern, because its temperature would otherwise drop significantly as it expands.

Siemens’ Bailie, who has worked for both Magnum and Range, estimated a compressed air project in Utah would use about half the natural gas as a modern gas-fired power plant with the same capacity. But any natural gas could be a problem in the long run, since California law requires 100% of the state’s electricity to come from climate-friendly sources by 2045.

Officials at the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power have “a little heartache” about the natural gas burned for compressed air storage, said Paul Schultz, the utility’s director of external energy resources. But they hope to eventually replace gas with hydrogen, a clean-burning fuel that can be produced by using renewable electricity to split water into its constituent elements, hydrogen and oxygen.

“The pathway to remove natural gas and use hydrogen is probably still 15, 20 years away,” Schultz said. “We’re just waiting for the technology.”

In a best-case scenario, hydrogen could be stored in some of the salt caverns at Intermountain and used to fuel not only compressed air energy storage turbines, but also turbines at the gas-fired power plant Los Angeles plans to build at the site.

In a worst-case scenario, renewable hydrogen could remain prohibitively expensive, or be hindered by technical or safety constraints — and Los Angeles could be forced to stop running the $865-million gas plant in 2045, even as Angelenos are saddled with the vast majority of the facility’s costs.

Wind, sun and wires

Salt and gas are just part of the story at Intermountain. Los Angeles officials say the infrastructure built decades ago for coal power could be repurposed as the center of a renewable energy hub, with solar and wind power charging the underground batteries at the salt dome.

The key is the 488-mile power line running from Utah to Southern California, known as the Southern Transmission System.

Energy companies are itching to build solar farms near Intermountain and send the electricity to California by way of the power line, which will have plenty of unused capacity once the coal plant shuts down. Several solar developers have proposed projects in the area, including L.A.-based 8minutenergy, the German conglomerate BayWa, South Korea’s Hanwha Q Cells and EDF Renewable Energy, a San Diego-based subsidiary of the French electric utility EDF.

Those projects could help sustain the economy of Utah’s Millard County after the coal generators shut down, said Ryan Evans, president of the Utah Solar Energy Assn. Solar farms employ only a few people each once construction is finished. But the tax revenues could be significant.

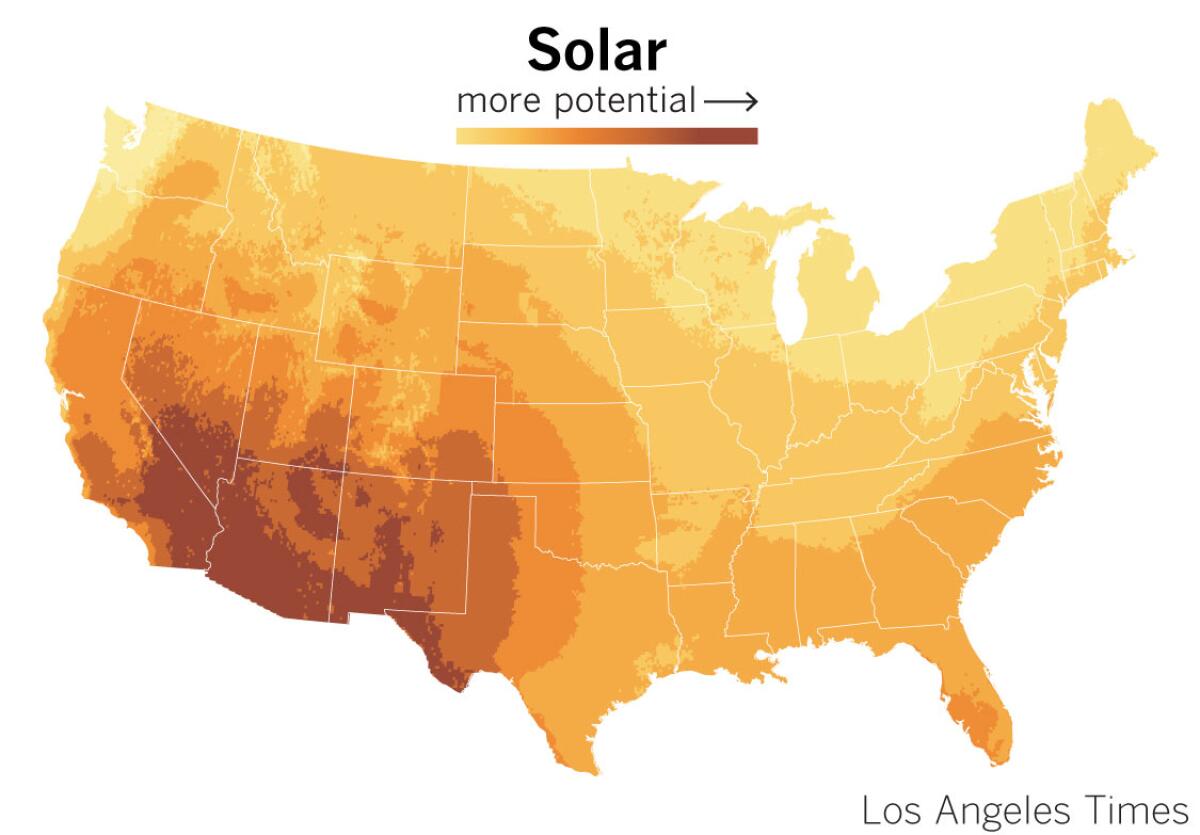

“We have these wide open lands that get tons of sun exposure but don’t have other uses,” Evans said.

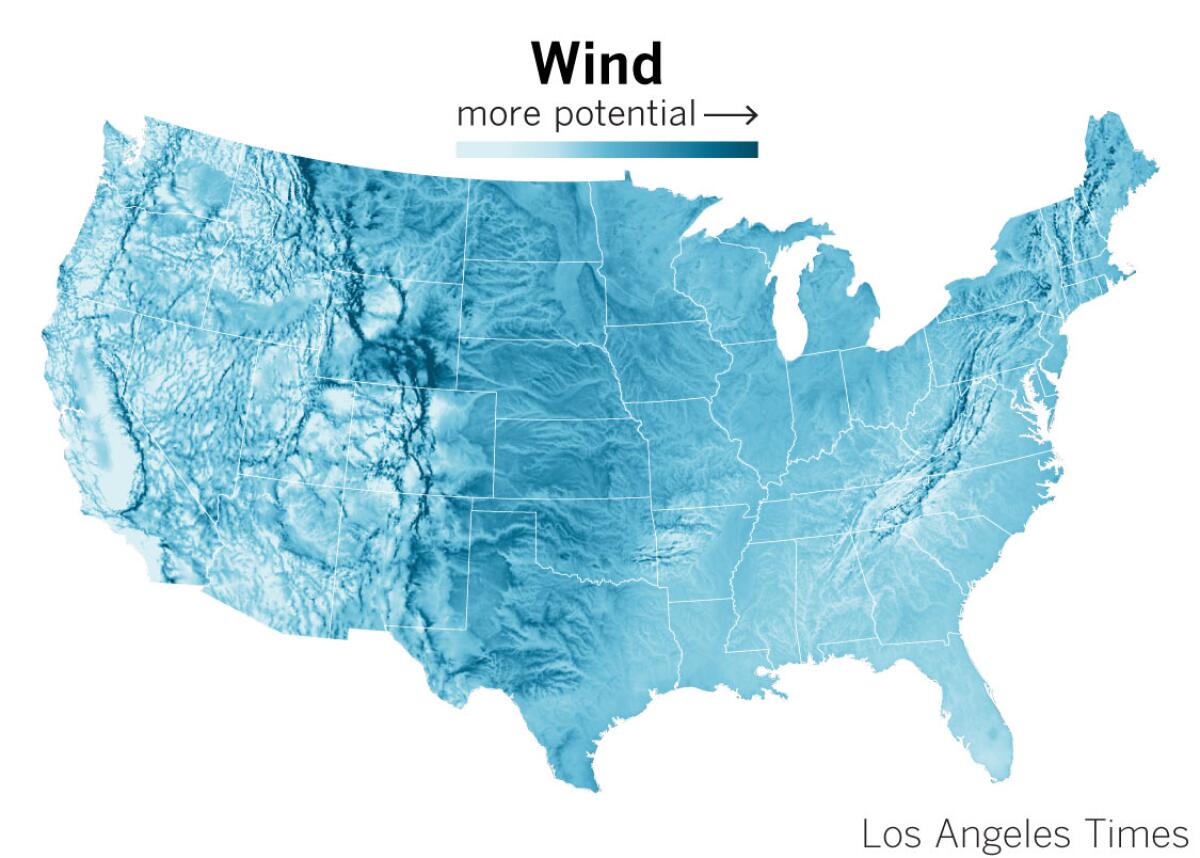

Nearby Wyoming, meanwhile, has some of the strongest winds in the continental United States. Renewable electricity generated by those powerful gusts could also make its way to Southern California via the Intermountain transmission line.

The conservative billionaire Philip Anschutz is already angling to make that happen.

Anschutz, who owns Staples Center and the Coachella Valley Music & Arts Festival, has spent more than $200 million permitting and beginning to build the country’s largest wind farm in Wyoming, along with a 730-mile power line to get the electricity to California. His company has held discussions with L.A. about routing their power line through Intermountain, and sending some of the wind energy to California through the existing 488-mile system.

Anschutz Corp. executive Bill Miller described the Southern Transmission System as an “incredibly valuable and viable asset” — especially in an era when environmental regulations and public opposition have made it difficult and expensive to build long-distance wires.

“It cannot be left stranded when they get rid of that coal plant,” Miller said.

Keeping the band together

Compressed air isn’t the only technology that might balance the variability of those solar and wind farms.

Grid managers could supplement sun and wind with resources that generate climate-friendly electricity around the clock, such as geothermal or nuclear power, or gas plants outfitted with carbon-capture technology. California could also work with other states to share more renewable energy across state lines, because it’s almost always sunny or windy somewhere in the West.

All those options face their own economic, technological or political hurdles. None of them will halt climate change on its own.

Neither will compressed air energy storage. But Los Angeles officials hope it’s part of the solution — and so do the Utah cities that partnered with L.A. to build the Intermountain coal plant.

“The fact that this is turning into an energy hub for next-generation energy technologies is very exciting for the Utah partners,” said John Ward, a spokesman for Utah’s Intermountain Power Agency. “They wanted to do whatever they could to keep the band together.”