Butterfly on a bomb range: How scientists have made the Endangered Species Act work

- Share via

Fort Bragg, N.C. — In the unlikely setting of the world’s most populated military installation, the Endangered Species Act is hard at work.

Here, as a 400-pound explosive resounds in the distance, a tiny St. Francis’ satyr butterfly flits among the splotchy leaves, ready to lay as many as 100 eggs. At one point, this brown and frankly dull-looking butterfly could be found in only one place on Earth: Ft. Bragg’s artillery range.

Now, thanks in great measure to the 46-year-old federal law, the butterflies live in eight more places on other parts of the Army base. And if all goes well, biologists will have just seeded habitat No. 10.

Experts estimate there are maybe 3,000 St. Francis’ satyrs, making them one of the rarest butterfly species on Earth. There are never going to be enough for them to get off the endangered list, but they’re not about to go extinct either.

In some ways, the tiny insect is an ideal example of the more than 1,600 U.S. species that have been protected by the Endangered Species Act — alive, but not exactly doing that well.

To some conservationists, just having these creatures around means the 46-year-old law has done its job. More than 99.2% of the species protected by the act survive, according to an analysis by the Associated Press. Only 11 species were declared extinct, and experts say all but a couple of them had pretty much died out by the time they were listed.

On the other hand, only 39 U.S. species — about 2% of the overall number— have recovered enough to be taken off the endangered list. That roster includes such well-known successes as bald eagles, peregrine falcons and American alligators.

Most of the species on the endangered list are getting worse, and only 8% are getting better, according to a 2016 study by Jake Li, director for biodiversity at the Environmental Policy Innovation Center in Washington.

“Species will remain in the Endangered Species Act hospital indefinitely. And I don’t think that’s a failure of the Endangered Species Act itself,” Li said.

::

The Endangered Species Act “is the safety net of last resort,” said Gary Frazer, assistant director of ecological services at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which administers the law. “We list species after all other vehicles of protection have failed.”

The legislation was passed with overwhelming support in Congress — the House voted 355 to 4 in favor and Senate approval was unanimous — and President Nixon signed it on Dec. 28, 1973.

The law was designed to prevent species from going extinct and to protect their habitat. It instructed two federal agencies — the Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service — to draw up a list of species that were either endangered or threatened with extinction.

Under the law, it is illegal to “harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture or collect” endangered animals, or to eliminate their habitats. At first, only animals were protected, but plants are now covered as well.

The law caused all sorts of environmental showdowns in the 1970s and 1980s — notably the fight over the construction of the Tellico Dam in Tennessee, which threatened the tiny snail darter fish. In the end, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the fish, but Congress exempted the dam from the law.

Now, the act is in contention once again. In September, the Trump administration changed the endangered species process in ways that some say weaken the law. One change would allow costs to industry to be taken into account when deciding how to protect species, critics say.

::

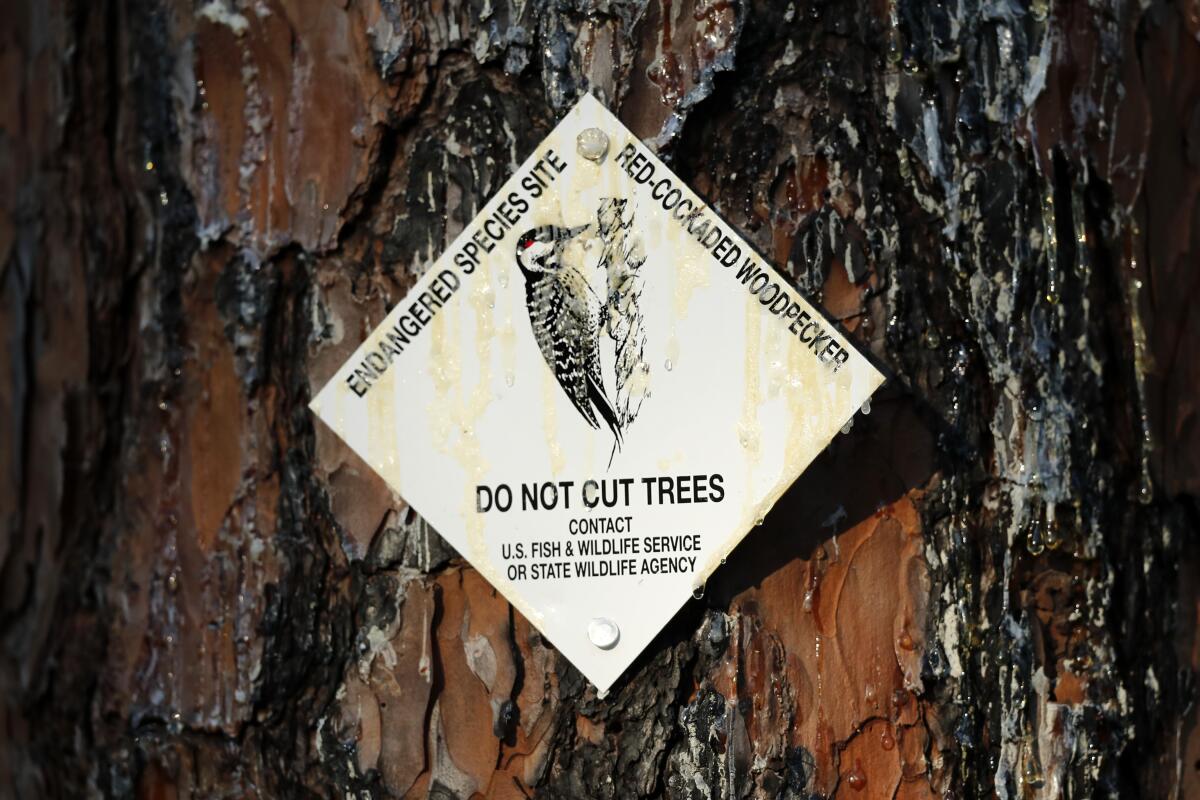

Even putting that aside, the act has its costs. Another species found at Ft. Bragg — the red-cockaded woodpecker — is a case in point.

From 1998 to 2016, the federal government spent $408 million on the red-cockaded woodpecker, making it one of the most expensive species on the endangered list. In 2016 alone, expenditures reached $25 million — more than 100 times what the government spent on the St. Francis’ satyr butterfly.

The small woodpecker is a member of the original class of 1967. It may soon fly off the endangered list or, more likely, graduate to the less-protected threatened list.

“Something is going right,” said Ft. Bragg Endangered Species Branch Chief Jackie Britcher, holding a male woodpecker in her hands as a group of biologists stood under trees with giant nets to catch, count and band the birds.

The woodpeckers live only in longleaf pines. But the trees have been disappearing across the Southeast for more than a century, due to development and suppression of fires. When naturally occurring fires were tamped down, other plants and brush crowded them out.

Unlike other woodpeckers, these birds build their nests in live trees, sometimes taking as long as a decade to drill a cavity and make a home.

In the 1980s and 1990s, efforts to save the woodpecker and their trees set off a backlash among landowners who worried about interference on their private property.

“I’ve been run off the road. I’ve been shot at,” said former Fish and Wildlife Service woodpecker official Julie Moore.

Army officials weren’t happy either: They were being told they couldn’t train in many places because of the woodpecker.

“We couldn’t maneuver. We couldn’t shoot because they were afraid the bird was going to blink out and go into extinction,” said former top Ft. Bragg planning official Mike Lynch.

By the 1980s, the red-cockaded woodpecker population was below 10,000 nationwide, said Virginia Tech woodpecker expert Jeff Walters. Biologists built boxes to serve as nests, attaching them to trees. The woodpeckers weren’t interested.

Then Walters tried something different. He put the boxes inside the trees. The birds started living in them.

Instead of prohibiting work on land the woodpecker needs, Fish and Wildlife Service officials allowed landowners to make some changes as long as they generally didn’t hurt the bird.

Such “safe harbor” agreements “effectively laid out the welcome mat for endangered species” without burdening the landowner, said former assistant Interior Secretary for Fish, Wildlife and Parks Michael Bean, who wrote the seminal 1977 textbook on endangered species law.

Meanwhile, Army officials were convinced to start setting fires to clear out the scrub. Now, about a third of the area burns every three years or so.

The result? When Britcher started, in 1983, there were fewer than 300 woodpecker families — with about three birds per nest — on Ft. Bragg, and the numbers were dropping. Now she counts 453 families on the base and 29 nearby. That’s well over the goal the Army set for itself.

At least 15,000 of the woodpeckers thrive on bases across the Southeast, where they’re best protected and counted regularly, Walters said.

The woodpecker is “an umbrella species,” biologists say. What helps woodpeckers is good for the St. Francis’ satyr butterfly and dozens of other vulnerable species.

It helps soldiers, too. They now have greatly improved training lands, Lynch noted.

He made that observation in the right field stands of the new minor league baseball stadium in Fayetteville, N.C. The community chose the name for the first-year team: the Fayetteville Woodpeckers.

People who once hated the bird have now embraced it as their own.

::

From 1998 to 2016, the federal government tallied $20.5 billion in spending on individual species on the endangered list. That’s based on an annual per-species spending report that the Fish and Wildlife Service sends to Congress, but it’s not comprehensive.

Over that period, more than $7 billion went to two species of salmon alone. (Salmon are expensive, in part, because helping them involves removing dams.) Seven species, mostly fish, ate up more than half the money expended under the act, according to the annual accounting figures.

About $3 million was spent to save the St. Francis’ satyr butterfly.

Nick Haddad, a Michigan State University biology professor and the world’s leading expert on the St. Francis’ satyr, got permission to go to the butterfly’s home, the artillery range.

He was expecting a moonscape. Instead, he said, “these are some of the most beautiful places in North Carolina, maybe the world.”

Because no one was venturing into the woods there, no one was dismantling beaver dams. No one was snuffing out fires. Aside from lingering fragments of munitions, the landscape was much like North Carolina before it was altered by humans.

The picky butterfly thrives amid the chaos. It needs a habitat that is disturbed, but only a bit. It needs a little bit of water, but not a lot. It needs fire to burn away overgrown plants, but not so much as to burn its food.

The butterfly appears only twice a year for two weeks each time. When it does, Haddad rushes to Ft. Bragg and joins a team of Army biologists to count the butterflies and improve their habitat. They install giant inflatable rubber bladders that mimic beaver dams and produce the minor floods that the butterfly needs.

Haddad and his students also tromp through the swamp and count the insects. As they take their census, they walk on thin planks placed in the water so as not to destroy the delicate leaves the butterfly feeds on.

“It couldn’t be better than this,” Haddad said, beaming as an egg-bearing butterfly takes flight. “When I see, every year, just a slight change in the right direction of the butterfly’s conservation, let me tell you, that inspires me.”

::

After years of criticism from conservatives that the endangered species program is ineffectual and too cumbersome for industry and landowners, the Trump administration has enacted 33 different reforms.

Among them: a change in the rules for species that are “threatened,” the classification just below endangered. Instead of mandating, in most cases, that they get the same protection as endangered species, the new rules allow for variations.

That is better management, said the Fish and Wildlife Service’s Frazer, adding, “It allows us to regulate really only those things that are important to conservation.”

Bean, the former Interior Department official, called the plan an “unfortunate step back, not catastrophic in its consequences.” Noah Greenwald, endangered species director of the Center for Biological Diversity, characterized the regulations as “a disaster.”

Li said the exceptions will allow species to be harmed greatly when they move from the endangered category to threatened status.

But the biggest problem, Li and others said, is that new species in trouble aren’t being added to the list. At its current pace, this will be the second consecutive year that more species come off the endangered species list than are added — an unprecedented occurrence.

Meanwhile, scientists across the globe warn of the coming extinction of a million species in the decades ahead.

Haddad is determined that the St. Francis’ satyr butterfly won’t be one of them.

Emily Dickinson called hope “the thing with feathers.” For Haddad, it’s about a thing with wings, the law that saved it and the Army officials who enforce that law.

“This is the thing that gives me hope,” Haddad said. “That’s where the Endangered Species Act had an impact.”

Borenstein writes for the Associated Press. AP data journalist Nicky Forster contributed to this report from New York.