Commentary: Eastbay catalog memories: It’s where a generation went to look at sneakers — and dream

- Share via

“It was my bible as a kid,” P.J. Tucker, the NBA’s savior of soles, the lord of laces, the king of kicks, told me early last month when I asked him about Eastbay, once a go-to resource for young athletes. Tucker wasn’t always able to put the finest fashion on his feet. Before earning the unofficial title of the NBA’s sneaker king, Tucker was just a kid with an empty wallet, a free subscription to a “magazine” and a dream.

“I could talk about Eastbay all day,” said Tucker, now a sneaker evangelist and forward for the Houston Rockets.

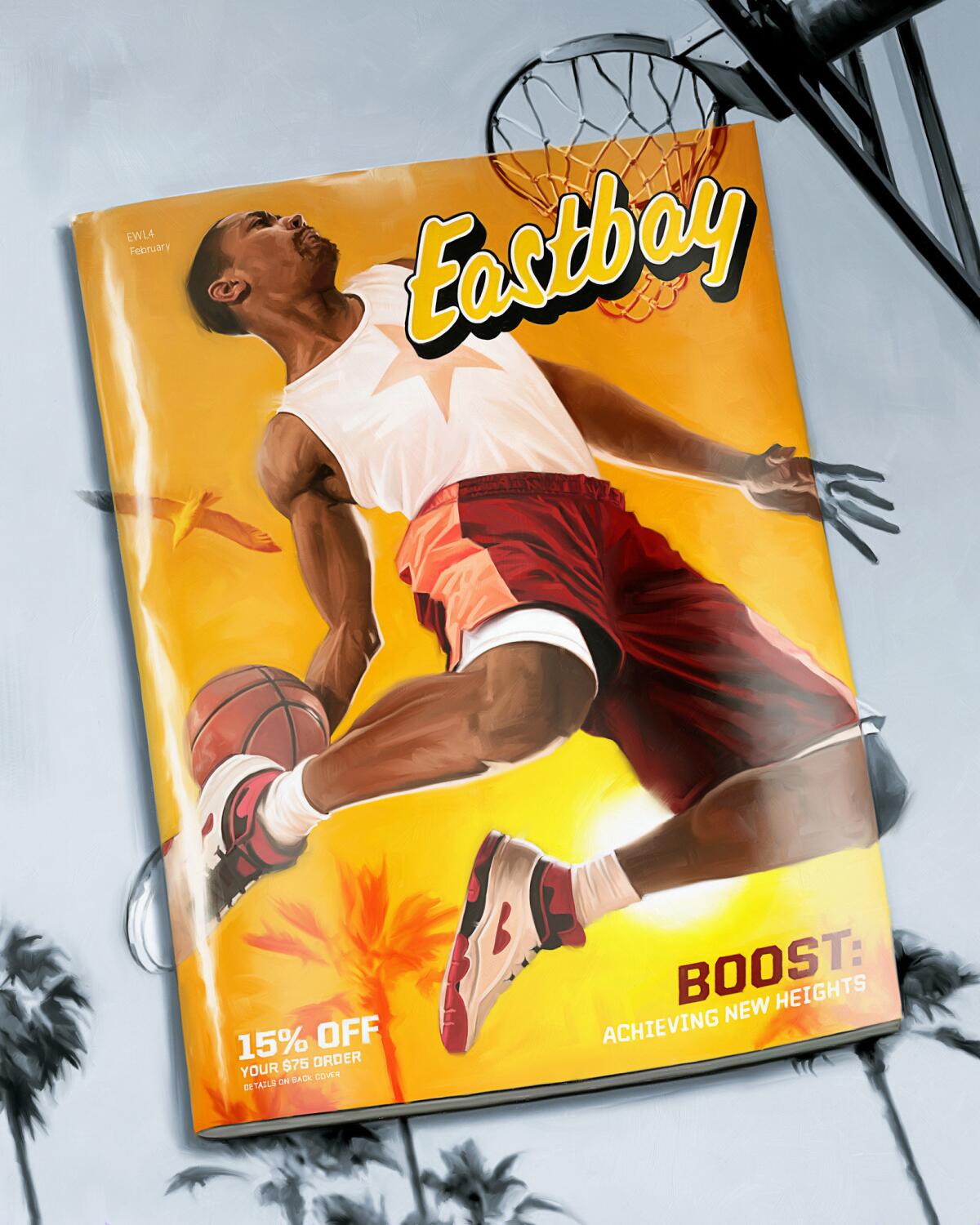

Direct-mail retailer Eastbay, which sells athletic footwear, gear and apparel, was founded in 1980 by a pair of high school coaches in Wisconsin before it grew into a national mail-order sporting goods behemoth. Eastbay also introduced its “magazine” — a catalog — decades ago. I remember its pages were littered with basketball shoes, track-and-field equipment, baseball gloves and football helmets. It was all there.

However, it was the sneakers, the Air Jordans, the Filas, the Reebok Pumps and the Adidas Superstars that had people like Tucker — and me — obsessed over Eastbay’s content.

Now calls to the company’s switchboard in Wausau, Wis., quickly get forwarded to automated answering in New York; some small-town charm lost in a list of corporate acquisitions and name changes.

Eastbay went public in 1995. Two years later, it sold to Woolworth Corp. for $146 million, which evolved into a company that also houses stores such as Foot Locker and Champs Sports under its umbrella.

All of that meant nothing to people like Tucker — and me — who eagerly waited for the seasonal catalog to arrive in the mail.

There on the pages, you’d see the newest shoes for every sport. You’d get technical details about materials, about new innovations. Every shoe was weighed to the 10th of an ounce. Specificity was everywhere — shoes for each track-and-field event could be purchased pages from the sneakers Michael Jordan, Charles Barkley and Kobe Bryant had on their feet.

“Mind you, I had no money to buy shoes, but I would just study Eastbay,” Tucker said. “I would look at it like it was a school textbook.”

My routine went this way: I’d grab the Eastbay out of the mail and head right to the couch, plopping down on my stomach with the catalog in front of me. For weeks I’d have my eyes on it, trying to figure out ways to persuade my parents that I needed the Nike Air Diamond Turf or the Converse Aero Jam or the Air Jordan 11s.

“You’d wait for it to come in the mail and spend days showing me all the shoes and clothes that you wanted,” my mother, Barb, recalled when I asked her a couple of weeks ago. “It was your wish list.”

It’s an experience, I learned, that I shared with players throughout the NBA, players from all kinds of backgrounds.

Some, like Tucker, never made a single order — the catalog itself was product enough. Others studied it so closely that they used it to win arguments with friends.

Lakers forward Lance Stephenson, a former Brooklyn streetball legend, studied the Eastbay texts just as Tucker did, marking up his favorite pairs in pen even if he knew he’d never get his hands on them. Now a nine-year veteran who has earned more than $30 million, designer shoes and limited releases spill out of Stephenson’s locker.

“I would circle all the shoes I liked but I never got them,” Stephenson said. “I was a sneakerhead; I always liked sneakers. When that book would come out and you could see all the sneakers before they even come out, it was like you were seeing [the future].

“My friends who didn’t get the book,” he said, “I used to tell them which sneakers were going to come out, and they’d be like, ‘You’re lying.’ And then I’d go and cut out the pictures and show them.”

Go into an NBA locker room, say “Eastbay” and get ready for the stories, like the one from Austin Rivers, who remembers trying to get his hand on the catalog before his brothers.

“Nobody was allowed to get the same shoes. So whoever got the magazine first could pick the best sneaker, and everybody else in the family would be hot,” he said. “We couldn’t copy each other.”

Other players like Brooklyn’s Spencer Dinwiddie would ask for Eastbay gift cards for birthdays and Christmas.

And players from a previous generation, guys including TNT broadcaster Chris Webber, would dig through the catalog’s pages, the only place where you’d see shoes in colors that would match your team’s uniform.

“It was the internet before the internet,” Webber said.

The catalog is still available today, but there’s no need for it. Every pair of shoes, every pair of equipment can be found and purchased with a quick internet search and credit card.

Now you don’t have to flip through the extra-thin pages, studying shoes you didn’t need for sports you didn’t play. That time can now be spent checking out players’ posts on Instagram.

In trying to figure out more about the Eastbay catalog that so many NBA players and I loved, I called Foot Locker’s corporate offices. I left voicemails. I wrote emails.

Whatever happened to the founders? How many people still get the catalog? How many at its peak?

They would’ve been good questions to get answered, but no one responded. So I settled for talking with people who loved the Eastbay catalog as much as I did, who spent hours of their childhood wishing their feet could be the same as Jordan’s or Bryant’s or Barkley’s.

My mom told me that we ordered some stuff from the catalog. I don’t remember. I just remember looking and wanting and wishing.

Maybe that’s what matters most.