The storyteller’s refuge

Novelist T.C. Boyle isn’t about to take the end of the world sitting down, especially not today. Just back from a monthlong book tour for “Drop City,” his novel of counterculture meltdown, he knows there’s no time to waste. The battle’s gone personal, and it’s not about developers versus tree huggers or hippies versus homesteaders.

This time it’s all about termites -- he points to a small cone of black granules on the window ledge above the back stairway -- and this living museum he calls his home.

Swarming insects don’t have anything on him. After all, he’s already faced down mildew, rot and a leaky roof -- everything you’d expect in a house that’s nearly 100 years old -- but here the stakes are always high, especially if you’re the custodian of a Frank Lloyd Wright design, and it happens to be the first he drew for the Golden State.

That Boyle, spinner of subversive tales about marijuana farming, illegal aliens and eco-terrorism, lives in a Wright house may come as a surprise. A tall lanky shape, dressed in black with red Converse high tops, who’s as apt to carry on about drugs and free love as he is about global warming and declining sperm counts, he might seem more at home in a rambling shed buried deep in Topanga Canyon or the penthouse suite of an Ian Schrager hotel.

But sit with him on the back deck -- one of his favorite places -- where you might catch him one summer evening barbecuing a mixed grill, and you’ll find a man at ease with his surroundings. From here you can look into the cathedral-like space of the living room or out into the brilliant green canopy of trees that surround the home.

“It’s quite wonderful here,” he’ll tell you, as if you need to be told. “It’s two stories up from the ground, and it’s like you’re floating in the trees. The overhang protects you from the sun, yet as the sun goes west, it can warm the area. It’s a magic sort of place.”

So who is this man, sometimes known as Tom Boyle or T. Coraghessan Boyle, who wears this home, this monument of aestheticism, so well around his shoulders? Like an animal trainer, he’s been putting the Four Horsemen through their paces since he stepped upon the literary stage in 1979, and now nearly 25 years and 14 books later, he’s got a bestseller on his hands in “Drop City.” But outside his novels, he is, for sure, a carefully cultivated mystery.

Look at the author photos on his books -- silver ear clip, carefully coiffed Vandyke and apricot frizz -- and you’ll be met with a formidable gaze and a beady eye. Strike up a conversation, however, and you’ll be surprised by his friendliness. This is a man who can be expansive and guarded all at once -- not quite a recluse but close to one.

You’re reminded of this as he walks you around the house, pulling out one key to open the guesthouse and another the cellar. Clearly he craves his privacy. So don’t expect us to tell you where he lives. Let’s just say it’s a well-heeled Southern California neighborhood, known for Gatsby-like estates (mostly Spanish Colonials), gated entrances and a surplus of high-end SUVs and exotic sports cars.

He’d also prefer you not see a photograph of the house from the street. So let’s put it in words: There’s a redwood fence, a brick path, a neatly trimmed lawn and a line of windows with delicate wood muntins shaded by deep, cantilevered eaves. Nor does he want you to wander through the private rooms of his home, and that’s just fine.

Perhaps you’ll find these restrictions a little frustrating, especially if you want to know more about the writer of such killer first lines as “I was living with a woman who suddenly began to stink” or “There was no exchange of body fluids on the first date, and that suited both of us fine” and such provocatively titled stories as “Rupert Beersley and the Beggar Master of Sivani-Hoota,” “She Wasn’t Soft” and “Killing Babies.”

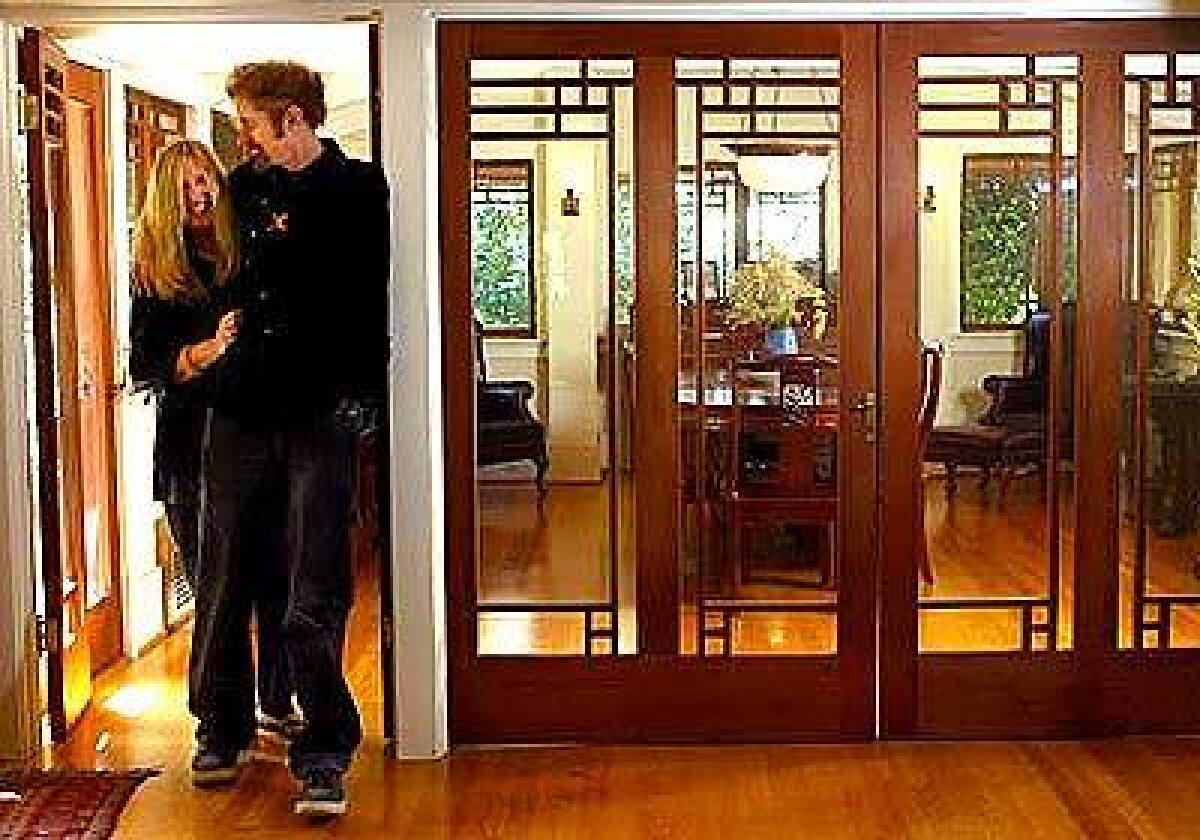

It only means you’re left to draw your own conclusions. Did his wife -- his college sweetheart no less -- Karen, for instance, with the beautiful blond hair who greets you at the door, inspire “My Widow,” the tale of a recluse who lives under a leaky roof surrounded by cats and the detritus of her life? Was the Hungarian puli, the little black dog with the dreadlocks who gnaws at your ankle (just be glad the other one’s upstairs), model for the dog-woman in “Dogology”? And is it Boyle himself -- his parents, his childhood -- who plays into “When I Woke Up this Morning Everything I Had Was Gone,” a surprisingly sad story of dissolution and poverty that appeared last month in the New Yorker?

While some questions must go unanswered -- you don’t get to be as popular as he is without drawing unwanted attention -- he is willing to talk to you about his relationship with the house.

It all began with a phone call 10 years ago this July. Like anyone who’s looked too long for the perfect house, he was about to give up. They’d been searching for almost a year, and the more they looked, the more their 1940s ranch-style home in Woodland Hills didn’t look so bad. Boyle had purchased the lot behind them -- to keep another home from being built there -- and he’d planted it with naturals, but suburbia had changed. “I wanted to leave L.A.,” he explains, “because of the population pressure. I think that in Woodland Hills alone the population had tripled. I just wasn’t enjoying it.”

Then came the phone call. Summer was almost over, a new semester about to begin at USC, where Boyle is a tenured professor, and all he wanted to do was get away. The High Sierra beckoned, and he had the idea for a new novel he was thinking of calling “The Tortilla Curtain.”

But Karen was on the line in tears. She anticipated him saying no and didn’t want to lose this chance. Frank Lloyd Wright designed it, she said, but Boyle was unimpressed, though conciliatory. He agreed to take a look. The home had been on the market for two years and originally was listed for more than $2 million, but then the recession hit and, as real estate agents will tell you, this isn’t exactly a home for Ozzie and Harriet.

First, there’s the floor plan. Laid out on a cruciform pattern with the fireplace at the center -- the living room flanked by the dining room and parlor -- there are no interior walls. Upstairs, the shape is slightly condensed; the bedrooms and baths are small, and there’s hardly any closet space. (Wright disdained rooms where you closed your eyes to sleep or stored things you didn’t need.)

Second, there is a certain tension -- a purposeful discomfort -- built into the design. To begin with, you can’t see the front door, and when you get there, you’re standing beneath an overhang that -- with a 6-foot, 5-inch clearance -- is more of a cave than an entry. Then you step inside, and the space is no better. Wright breaks the tension gloriously with an adjacent two-story ceiling, but for some people that might not be enough. And if you’re looking for a grand staircase, a garage or a family room per se, forget it.

So the price dropped to less than half the original asking price, and as Boyle was about to be paid for the movie rights to his novel “The Road to Wellville,” the timing was just right. By noon, they’d opened a 30-day escrow.

Sitting in the living room with its tall eastern-facing windows, looking out into the trees and, opposite, 15 of his books lined up on a clutterless fireplace mantel, you might find it difficult to imagine Boyle living anywhere else. The clean lines, the open spaces -- accented by low wood-framed Stickley and other Craftsman sofas and chairs, mica lamps and blue and red Oriental-style throw rugs -- suit him well, and while he describes restoring the home before they moved in as a fistfight between Karen and himself (“we use lightweight gloves”), he’s quick to credit her impeccable taste. She’s more modest, believing their greatest luck was finding a home that had been lived in by only three previous owners, most of whom were too old to embark on any extensive remodeling program.

Boyle calls this his treehouse, and were you to open all the windows, the breeze would blow straight through, the indoors and outdoors suddenly indiscriminate. When describing the experience of living here, he speaks easily about the pleasures of listening and watching rain pour like waterfalls off the roof during a storm, or about spending the night outdoors sheltered beneath the expansive sleeping porches, or about fixing dinner, listening to NPR, as the sun sets, filling the rooms with a dusky glow.

The temptation may be to rarify this home, but it is, he reminds you, a completely functional space, where he and Karen raised their three children, Kerrie, Milo and Spencer who, from the color 8-by-10s atop the upright piano in the dining room, seem just like the kids next door.

Wright often bragged that he could shake houses out of his sleeve, and given the history of this house, you might have believed him. Designed in 1909 and built in 1910 as the summer residence for a wealthy Central Valley farming family, the home was a commission that he took during a particularly creative and troubled period in his life. He was in his mid-40s, exhausted, disappointed in his marriage and in love with another woman. He was ready to make a break, but he needed money.

Whether he finished the drawings himself or left them to his staff is an unanswered question. More to the point, however, is that he soon abandoned his wife, their six children and his practice and sailed to Europe with Mamah Cheney, the wife of a client. It was a trajectory that would lead to divorce, scandal and much worse. On Aug. 15, 1914, while Wright was away in Chicago, a worker at Taliesin, Wright’s famed country home, inexplicably set fire to the house, then murdered Cheney and six guests.

It is an often forgotten chapter in Wright’s rather epic life, which seems perfectly tailored for Boyle, whose ongoing preoccupation with untold American stories (John Harvey Kellogg, and Stanley McCormick, scion of Cyrus) is now focused upon mid-20th century sexologist Alfred Kinsey. Perhaps it is no coincidence that Boyle keeps a picture of Wright on a crowded bulletin board in his office, a small aerie adjacent a sleeping porch. Their lives are more intertwined than it may seem.

Both men had tumultuous childhoods: Wright, abandoned by his father when he was a teenager, and Boyle, raised by two alcoholic parents until he blasted out of a life of drugs, booze and petty crime into the world of books. Throughout his life, Wright was a lightning rod for controversy, and Boyle’s world -- for all the apocalyptic doom, for all the cultures that careen and collide, for all the fires, floods and animal life run amok in his fiction -- has been noticeably calmer, but there is in both men’s lives a manic dedication to their craft and, in their work, a comparable degree of polemic.

Nowhere does that polemic become clearer than in their devotion to the role of nature in our lives. In remembering Cheney, Wright tried to console himself and assuage the terrible memory of her death. “Nature knows neither Past nor Future,” he wrote, “the Present is her Eternity.”

“Wright always kept his eye on nature, and so have I,” says Boyle. “My books look at people as an animal species living within the context of nature, and I suppose you could say the same of Wright.”

This context is best experienced just outside the living room, where a tangle of Victorian box and black acacia trees, scrub oaks and eucalyptus crowd the sky, leaving cotoneaster, yellow-flowering oxalis, platter-sized nasturtiums, Mexican sage, English ivy and bird of paradise to fight among themselves for available light.

Boyle calls this his jungle, and indeed, coming upon the house from this angle is like stumbling upon a Mayan temple buried deep in the Yucatán. Board-and-batten redwood zigzags monumentally across right-angled facades; dramatic roof lines cascade high overhead; and the broad expanses of windows skirt each story.

Within this jungle are Boyle’s beloved critters: the gophers, scrub jays, doves, raccoons, Monarch butterflies, possible skunks and occasional hawks and coyotes, attracted to the pond he dug and landscaped near the southern property line. It is here, working to create this jungle with its fallen trees and stone-lined paths, that Boyle wanders dreaming of plot lines, character and behavior.

Unlike most of his other commissions, Wright never visited this site before drawing the plans. The home existed in his imagination until, nearly 50 years later, he passed through Southern California on the way to Marin County, where one of his last projects, the civic center, would soon be built. He died not long thereafter, April 9, 1959, an eternity after sketching this landmark.

Boyle may deny that his house or this setting has influenced his fiction. “Ray Carver,” he’ll say, evoking the memory of the great short story writer who also was his friend, “once said that when he was successful and living in Port Angeles, looking at all that water was a distraction to him. Me? I am used to looking at a wall. Now I am able to gaze out to the trees. It’s not a long view; it’s the trees and birds, and if I look casually to my left, I can see the mountains.”

But he cryptically understates it. For a writer whose fictions so handily demolish any cherished illusions we hold about the present, the past or future, his home is more than a home. It is a place to gaze out upon the world, an island out of time to imagine, if necessary, the end of time.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.