David Myers’ culinary empire in flux

These are the last days of Sona, the elegant restaurant on La Cienega Boulevard that has been a fixture of Los Angeles’ fine-dining scene for nearly eight years. On Saturday, after the final mignardises go out to the last diners, the restaurant will shutter — at least for now.

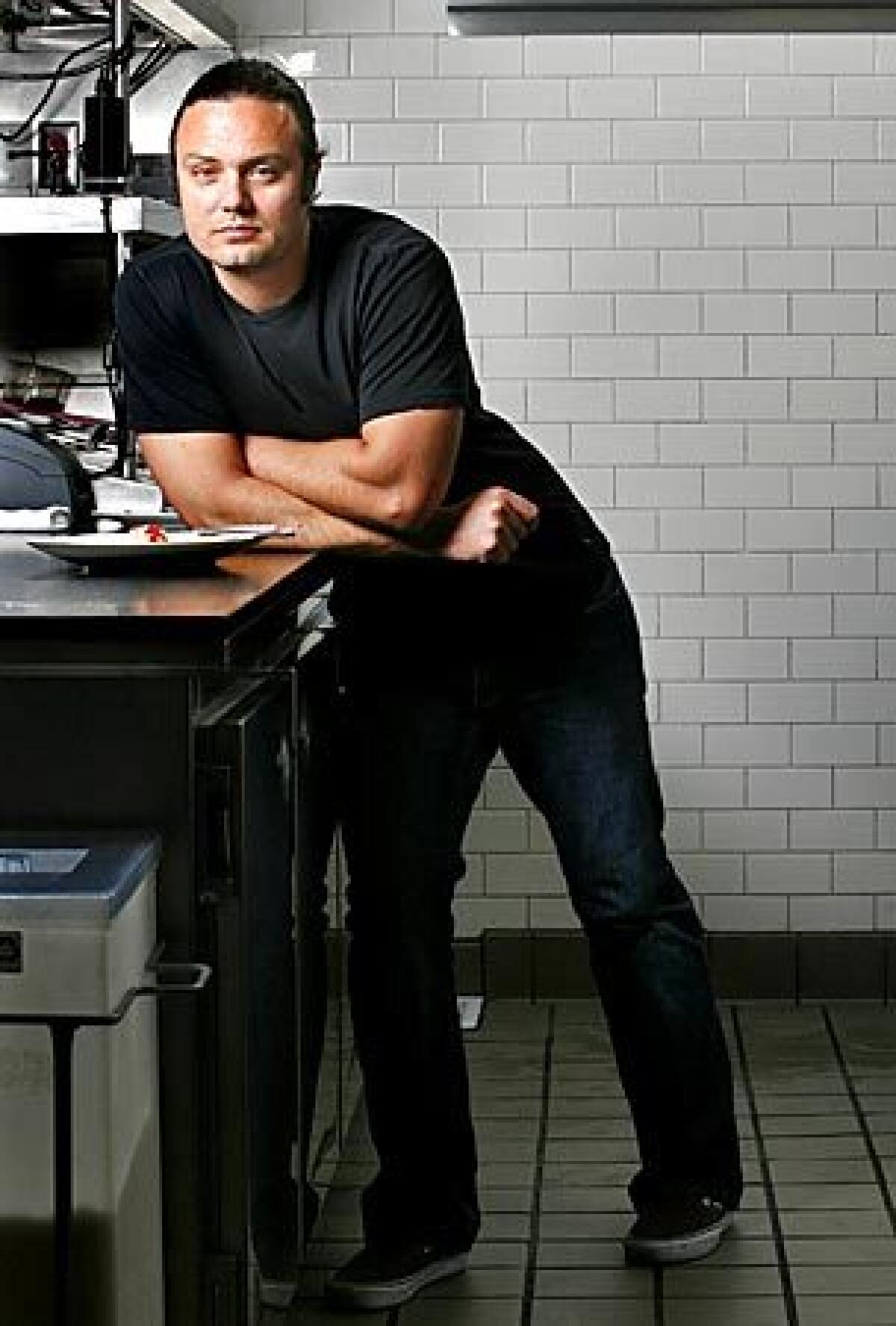

A little more than a year ago, David Myers, Sona’s ambitious, photogenic chef-owner, was at the helm of an empire. It included not only his flagship Michelin one-star restaurant but also modern brasserie Comme Ça, a small chain of Boule pastry shops, a commercial baking operation and Italian restaurant Pizzeria Ortica, with more on the way.

But with the announced closing of Sona, only Comme Ça and Pizzeria Ortica will remain, and those only with new chefs and new management after a round of firings and departures.

Apparently, there have been some cracks in the House of Myers. In September, Myers’ Swiss partners pulled out of the business, and Sona filed for Chapter 11 protection from creditors. A settlement with a lender forced the sale of assets, including much of the restaurant’s million-dollar wine inventory. And in March, Myers announced that Sona, where a fashionable crowd could indulge in nine-course tasting menus and plenty of Bordeaux, would close its doors.

Few have had the outsize aspirations of the 36-year-old chef from Cincinnati who worked for luminaries such as Charlie Trotter in Chicago and Daniel Boulud in New York before landing in Los Angeles. He has youthful looks, wavy brown hair and a penchant for surfing, and proved to be a promising chef with a gift for making splashy promises.

He maintains that he will reopen Sona in a new location in 2011. A second Comme Ça is slated for the Cosmopolitan of Las Vegas hotel, which is still under construction. He also has his sights set on Tokyo. “We have a new opportunity,” he said. “Companies evolve, restaurants evolve.”

Though the recession of the last couple of years has left many restaurateurs in financial straits, Myers denies that Sona’s closure is related to the economy. So what happened?

Business issues

The problems that caught up with Sona offer a glimpse into a restaurant business that increasingly requires a chef to be more than a creative cook with big ideas.

“David Myers is a great creative person … and we really appreciated that to the very end,” said Otto Schmid, who helped form Sona’s former managing company, FoodArt Ventures Inc., with his son Basil Schmid and Myers. “But his way of managing companies, managing people and accepting cost controls needs some further development.”

But the implosion of Sona is probably far more complicated. “David, Basil and Otto all bought into their own press releases,” said Michael Morris, FoodArt’s former president of construction and development. Morris claims in a lawsuit against FoodArt, filed in L.A. Superior Court, that he is owed more than $300,000 for construction-related expenses. Neither Otto nor Basil Schmid nor Myers were available to comment.

When Sona opened in 2002, the restaurant was considered groundbreaking. He and his then-wife, pastry chef Michelle Myers, were a culinary “it” couple. They’d met “over gnocchi,” as the story goes, while he was a sous chef and she a pastry chef at Joachim Splichal’s restaurant Patina.

Together, they wowed the critics with their food. “As other young chefs turn out easy-to-cook, easy-to-please American comfort food, David and Michelle Myers are taking chances,” Times restaurant critic S. Irene Virbila wrote in her review. “When their intricate, cerebral cuisine works, eating at Sona is one of the most exciting dining experiences in the city.”

Food & Wine magazine gave Myers a coveted “Best New Chef” award for 2003, dubbing him “one of the most talented young chefs in America.”

In 2004, Michelle opened Boule across the street from Sona, replete with pristine chocolates, pâtes de fruits, macarons and blue-green packaging that evoked the brand stature of Tiffany.

In the last few years, Myers expanded at a head-turning pace. Even after he filed for divorce from Michelle in 2007 and she was noticeably absent from the day-to-day operations, he moved Boule into a bigger space in October that year and called it Boule Atelier, with the addition of a bread baker from Japan determined “to change American bread culture.”

Comme Ça opened the same month, again to rave reviews and big crowds. A smaller Boule store opened in Beverly Hills that December. The following spring, he announced another Comme Ça near South Coast Plaza, though that never materialized. But in January 2009, Pizzeria Ortica debuted in Costa Mesa.

Midas touch

Each opening seemed to prove Myers had tapped into some kind of dining gestalt. Los Angeles had never seen a bakery like Boule, which was more Rue Saint-Honoré than La Cienega Boulevard. Comme Ça was the first of a wave of bistro-inspired restaurants that washed over L.A. And its notable cocktail program was at the forefront of the arrival of the “cocktail revolution.”

In between restaurant and bakery openings, Myers starred in a TV show on the Fine Living Network titled “Shopping With Chefs” and appeared on Food Network’s “Iron Chef America.”

Armed with his publicist, he has a knack for parlaying bad news into announcements for new projects. When Myers suddenly closed the Boule pastry shops early last year, he simultaneously announced that he was moving his baking operation into a commercial space in Culver City and that he would open retail shop Comme Ci Bakery to meet the “incredible demand for our breads.” He also said he would be opening Boule in Tokyo.

“Boule never made money and finally had to be closed to stop the bleeding,” said Otto Schmid, who was chairman of FoodArt, the umbrella company for all the businesses.

The commercial bakery was short-lived, and neither Comme Ci Bakery nor Boule in Tokyo ever opened.

By the end of September 2009, Sona LLC had filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection and FoodArt had exited. Filings reveal that Sona was losing as much as $33,568 a month in summer 2009 and that liabilities were $3.6 million as of the end of August. A $1-million loan was foreclosed on by lender GemCap and led to a sale of the restaurant’s collateral, including wine and equipment.

When asked why FoodArt withdrew from the business, Myers said: “I don’t know. My previous partners wanted to exit the fine-dining business. They were from a different country.”

According to the bankruptcy filings, a finance director hired by FoodArt in March 2009 implemented “financial and operational processes and procedures that were nonexistent” before he arrived.

Sona also never made money, says Otto Schmid. “It was a business, it didn’t work, that’s it,” he said.

Myers wouldn’t respond to questions about the restaurant’s financials.

When FoodArt and Myers split in September, the chef formed David Myers Group with investor Walter Schild, founder of Los Angeles marketing agency Genex. Myers wouldn’t say whether he still owns part of the business and Schild didn’t return a call for comment.

Staff purge

A slew of firings came on the heels of the transition to David Myers Group. It was a somewhat surprising sweep from someone whose staff-bonding efforts, including boot camp-style workouts at the beach, were once featured in Gourmet and People magazines. Managers, a sommelier and the executive chef at Comme Ça say they were summarily replaced. Some former employees say they were told that they “did not fit the concept.” Myers declined to comment.

Comme Ça executive chef Michael David, who had helped open Sona and the Melrose brasserie, says he was fired in December because he and Myers didn’t agree on his role in the new company. “I had hopes and expectations. The way that I had seen my future involved a certain type of growth, expansion,” David said. “But that opportunity didn’t exist.”

Last month, executive chef Steve Samson departed Myers’ Italian restaurant in Costa Mesa to work toward opening his own restaurant. The Pizzeria Ortica website lists Samson as chef-partner, “but it didn’t work out that way,” he said. He added that his leaving had nothing to do with Myers.

Myers has enlisted outside help. Allie Ko, a partner of La Cachette Bistro in Santa Monica, was brought on as a consultant for David Myers Group. Ko says she doesn’t have a consulting business but was helping Myers as a friend.

Even if his plans don’t always pan out, Myers is emphatic about opening more restaurants, at the same pace as ever. Besides the planned opening of Comme Ça in Las Vegas, he’s counting on more Pizzeria Orticas. “We’re incredibly focused on opening Pizzeria Ortica in L.A.,” he said. “We’re looking seriously at a couple spaces right now.”

And Myers has plans to push into Tokyo, where he says he will be opening a pastry shop and a “Sona-esque” cafe in September at Mitsukoshi department store in the Ginza shopping district. “It’s been a dream of mine to do something in Japan,” Myers said. A representative of Mitsukoshi in Tokyo confirmed a fall opening of a restaurant from Myers in a new annex of the store.

As for Sona, Myers says he already has a location but won’t say where it is. He did say that New York-based Adam Tihany would design the space and that chef de cuisine Kuniko Yagi and pastry chef Ramon Perez would return to their posts.

“There’s a certain time when it’s time to move on,” Myers said. “We’re leaving on a high note.”

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.