Japan’s ingredient du jour: shio koji

- Share via

The latest trendy cooking ingredient in Japan is a fungus. And that fungus is spreading. Professional and home cooks in Japan are crazy for it, and it’s flying off the shelves at Japanese markets in the U.S., too.

They’re using shio koji -- a fermented mixture of koji (rice inoculated with the special -- and safe -- mold Aspergillus oryzae), shio (sea salt) and water – as a seasoning in place of salt for its powers of umami.

Japanese supermarkets carry bottled salad dressings and sauces touting shio koji as an ingredient. The popular Japan-based burger chain Mos Burger this summer introduced a limited edition shio koji burger. “Moldy Mos Burger Confirms Koji Boom,” read a Japan Times blog headline in June. Famed Tokyo ramen chef Ivan Orkin tweeted: “Shio koji burger at Mos Burger umami bomb extraordinaire!”

There are blogs, websites, cooking videos and even a cartoon character devoted to the stuff, which some have dubbed a “miracle condiment,” the “new MSG” or the “next soy sauce.” (Not bad for something that looks like beige sludge and smells like slightly sweet sweaty socks.) It marinates meat, chicken and fish; makes quick pickles; and can be added to both savory and sweet dishes.

“It’s really great for [tempura] fritters, chicken and pork chops,” says Yoko Maeda, a private chef and food stylist who recently hosted a shio koji cooking class at her home in Marina del Rey. “I bet it would be good in pancake batter.”

A. oryzae has been used for thousands of years to make miso, soy sauce and other traditional Japanese foods. The Brewing Society of Japan has dubbed it the “national fungus” for its importance in brewing sake. Its key selling point: the mold’s ability to convert proteins into enzymes, inlcuding glutamic acid -- the enzyme responsible for umami. (It also converts starches into sugar, which is vital to sake making.)

Myoho Asari, a 9th-generation koji maker from Saiki in southern Japan, has been proselytizing the benefits of shio koji, recently leading classes in New York and Los Angeles. Her family has been in the business of making koji – innoculating rice with A. oryzae spores – for more than 300 years, originally for miso and soy sauce. A few years ago she, among other koji makers, saw an opportunity to diversify by marketing salt and koji as a seasoning for cooking.

The shio koji craze tracks a broader culinary trend in all things fermented. The Nordic Food Lab, the research workshop affiliated with the restaurant Noma in Copenhagen, has experimented with koji, growing mold on steamed buckwheat and then fermenting miso made with yellow split peas.

David Chang of the Momofuku empire of restaurants in New York is a confessed fermentation geek who has been using powdered koji as a seasoning. Chang also has contributed to an article in the International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science: “Defining microbial terroir: The use of native fungi for the study of traditional fermentative processes.” That includes reports about his experiments in making koji with both A. oryzae and naturally occurring molds in his culinary test lab.

On a recent weekend at Maeda’s apartment, Asari stood in a pale blue kimono at a kitchen counter mixing up a batch of shio koji. Through a translator, Asari -- who is also a longtime Girl Scout leader, with a sunny disposition -- tells a dozen rapt students about the goldmine of enzymes in koji: Amylase transforms starches into simple sugars; protease splits proteins into amino acids; and lipase breaks down fats. These are the systems that multiply umami, she says.

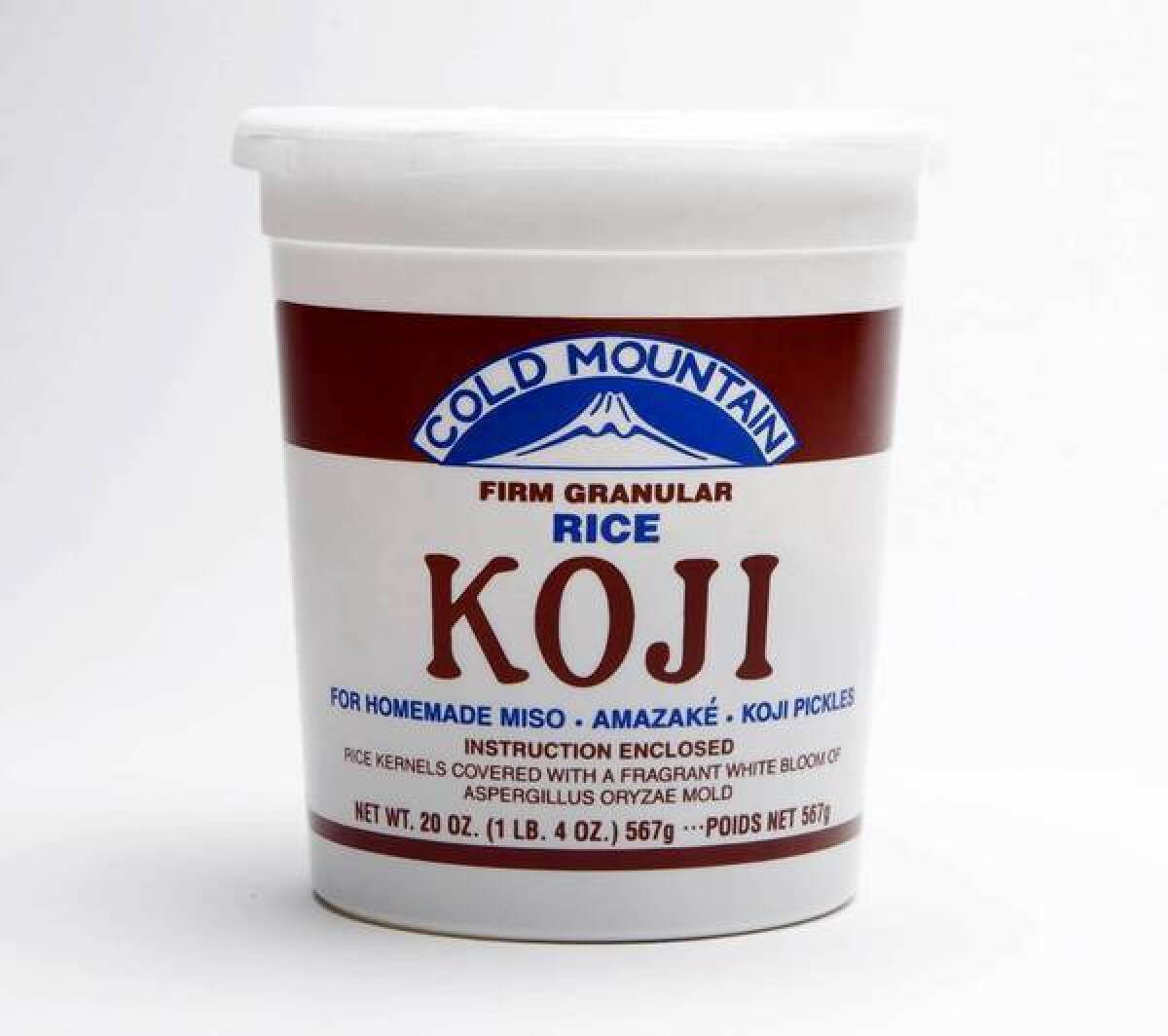

Tubes of prepared shio koji can be purchased at Japanese markets. But it’s easy to make yourself, and it’s far less expensive. The initial mixing of koji (inoculated rice sold in small tubs), sea salt and water requires a modicum of finesse but no more work than heating water and stirring. Then it’s just a matter of letting it ferment for about a week to reach full flavor, stirring it once a day. (See step by step.)

Shio koji is substituted for salt in recipes. Asari has written several cookbooks, adding shio koji to soups, salads, pasta, preserves and more; there’s shio koji meatloaf, shio koji bagna cauda, shio koji spaghetti carbonara. As a general rule of thumb, Asari recommends substituting 2 teaspoons of shio koji for 1 teaspoon salt. Or, use the golden ratio of 1:10 – that’s the weight of shio koji to total ingredient weight, so for every 100 grams of ingredients, use 10 grams of shio koji.

Start by using it simply, she suggests. Dress raw vegetables with it for a quick pickle. Make a tuna poke with it – diced sashimi-grade tuna tossed with shio koji and lemon-dressed avocado. Shio koji‘s transformative powers work pretty miraculously as a marinade for meats. Asari passes around pan-roasted chicken breasts that have been marinated with shio koji overnight, and it is umami-tastic. “This is the best chicken I’ve ever had – it’s delicious,” says one student. “And I don’t even like chicken.”

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.