California is now paying for people to test their drugs for fentanyl

As the death toll from the nation’s opioid crisis swells, California officials have launched an experiment: paying for people to test their drugs for fentanyl.

Fentanyl, an opioid that is up to 50 times stronger than heroin, is responsible for a growing number of overdose deaths each year. Typically manufactured as a white powder, it can be mixed into other drugs such as heroin and cocaine without the user knowing, but with extreme consequences.

“Fentanyl can kill you at first use — that’s why there’s incredible urgency,” said Dr. Kelly Pfeifer, who studies the opioid epidemic at the California Health Care Foundation.

Experts are unsure why fentanyl is showing up in so many drugs, and it appears to be happening more often. Reported deaths from fentanyl in California tripled between 2016 and last year.

Amid the fentanyl epidemic, test strips that detect the opioid are growing more popular not only in California but nationwide, with New York state and several overdose prevention programs across the country already using them.

But experts warn that they’re an imperfect solution. The tests haven’t been approved by federal regulators, and some experts have concerns about the accuracy of the results. Some public officials are reluctant to offer them.

Dr. Daniel Ciccarone, a UC San Francisco professor who studies heroin use, said the tests’ popularity, despite limited evidence of how well they work, underscores the severity of the opioid epidemic and the emerging problems with fentanyl.

“The crisis that is fentanyl is rapidly evolving and increasingly deadly, and it hasn’t turned around,” Ciccarone said. “I just see desperation.”

In May last year, the California public health department began paying for needle exchanges to distribute the strips to drug users.

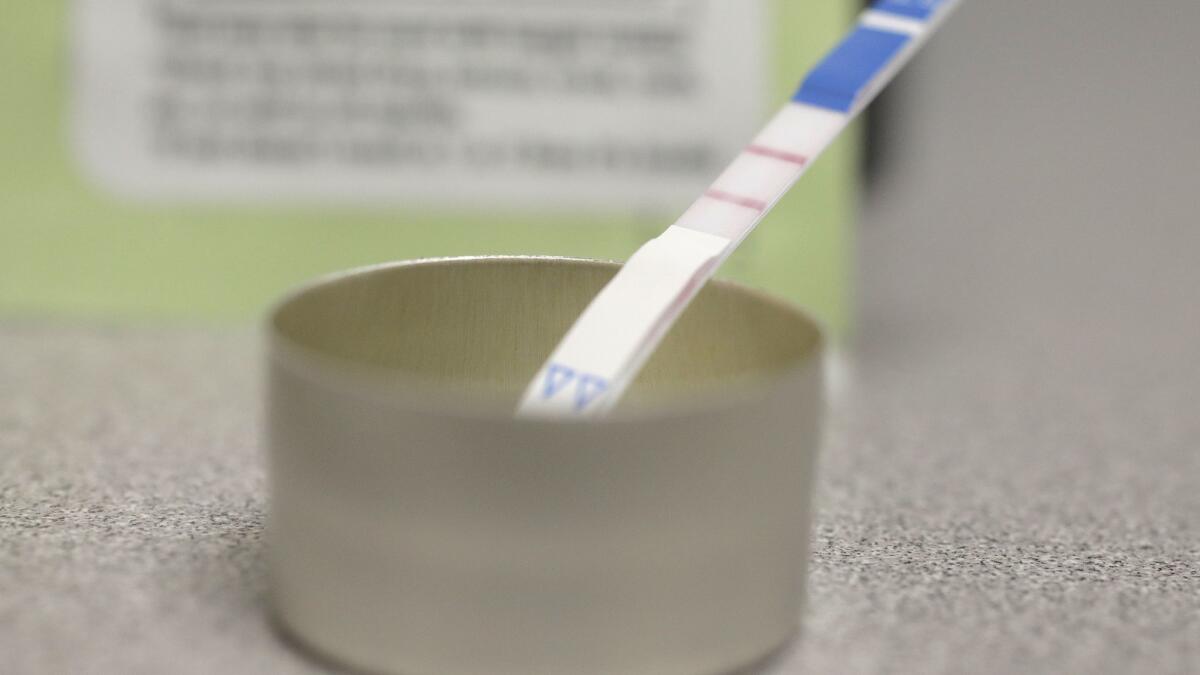

The tests, which are manufactured by a Canadian company and cost $1 each, function similarly to a pregnancy test. Users mix a little bit of a drug with water and then dip the strip in for several seconds. Five minutes later, they’ll see their result.

One line, there’s fentanyl. Two lines, there’s not.

Michael Marquesen, executive director of needle exchange Los Angeles Community Health Project, said the tests have shown that 40% of the heroin in Hollywood contains fentanyl. Dealers sometimes add fentanyl to heroin to provide a stronger high, experts say, but too much can quickly stop someone’s breathing.

“The overdose rates in Hollywood are through the roof,” Marquesen said. “They keep rising every month.”

Marquesen said that giving out the strips allows him to warn people about the dangers of fentanyl and also teach them how to use naloxone, a medication that can reverse an opioid overdose.

About half of California’s 45 needle exchanges distribute the fentanyl strips, according to state health officials. The state has so far spent about $57,000 on the tests, officials say.

But many believe the strips shouldn’t be at just needle exchanges.

Fentanyl is increasingly showing up in nonopiates, including methamphetamine, MDMA and counterfeit prescription pills. Three men who died in Los Angeles late last month are believed to have overdosed on fentanyl-laced cocaine.

Marquesen said the growing presence of fentanyl in party drugs mimics the trend that has played out in other cities.

“We’re a little bit behind everybody else, but we’re still following the same timeline,” he said. “I’m sure it’s going to show up everywhere.”

Dr. Gary Tsai, medical director of Los Angeles County’s health department’s substance abuse prevention and control division, said officials are considering offering the test strips more widely, but he worried about their accuracy.

Fentanyl was first developed as a pharmaceutical painkiller, and is still prescribed to patients. The test strips were developed to test for the medication in patients’ urine, and haven’t been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for testing drugs directly.

Tsai pointed out that the tests were made for pharmaceutical-grade fentanyl, so the kind available on the street might not be an exact match.

“I wish I could have more confidence in the fentanyl test strips,” he said.

Ciccarone, the UCSF professor, shared some concerns. He said the tests appear to detect minuscule amounts of fentanyl that a person wouldn’t be affected by. He worries that users will ultimately begin ignoring the results if they always come back positive, he said.

“It’s too darn sensitive,” he said.

Others, though, pointed to promising evidence. A recent Johns Hopkins University study found that the strips could detect when fentanyl was present in drug samples nearly 100% of the time.

“They might be a little bit on the sensitive side … but from a practical point of view it’s better to have a drug user exercising caution,” said Dr. Peter Davidson, who studies opioid overdose prevention at UC San Diego. “I don’t think that’s a huge problem.”

The study also found that 70% of drug users would modify their behavior if they knew fentanyl was in their drugs, including not taking the drug or buying it from a different dealer.

Ken Osepyan, harm reduction manager at the Pacific Pride Foundation, which runs needle exchanges in Santa Barbara County, said most users are unlikely to throw out their drugs completely, but may decide to take extra precautions. He said that 75% of heroin in the region has come back positive for fentanyl.

To avoid overdoses, Osepyan reminds users to start with just a little: “You can always do more, but you can’t do less.”

The test strips, developed by Toronto-based biotechnology company BTNX, were originally repurposed by a clinic in Vancouver a few years ago. But sales in the United States have been skyrocketing in the last year, said company CEO and founder Iqbal Sunderani.

Already, Sunderani has sold 205,000 test strips to American customers in 2018, with the state of California as his biggest customer and with continued interest from all corners, he said.

“It’s quite heartbreaking when you hear the stories,” he said. “We have people calling when they’ve lost children.”

However, Sunderani sells only to governments and harm reduction programs, not to individuals. Though he’s encouraged by early evidence showing the tests work directly on drugs, he’s still worried about the possibility of someone getting a false negative and then overdosing.

“The tests are designed for urine and not for substance,” he said. “You don’t want to give people a false sense of security.”

soumya.karlamangla@latimes.com

Twitter: @skarlamangla