Aquascaping: Aquarium meets terrarium in the Japanese-inspired design practice

- Share via

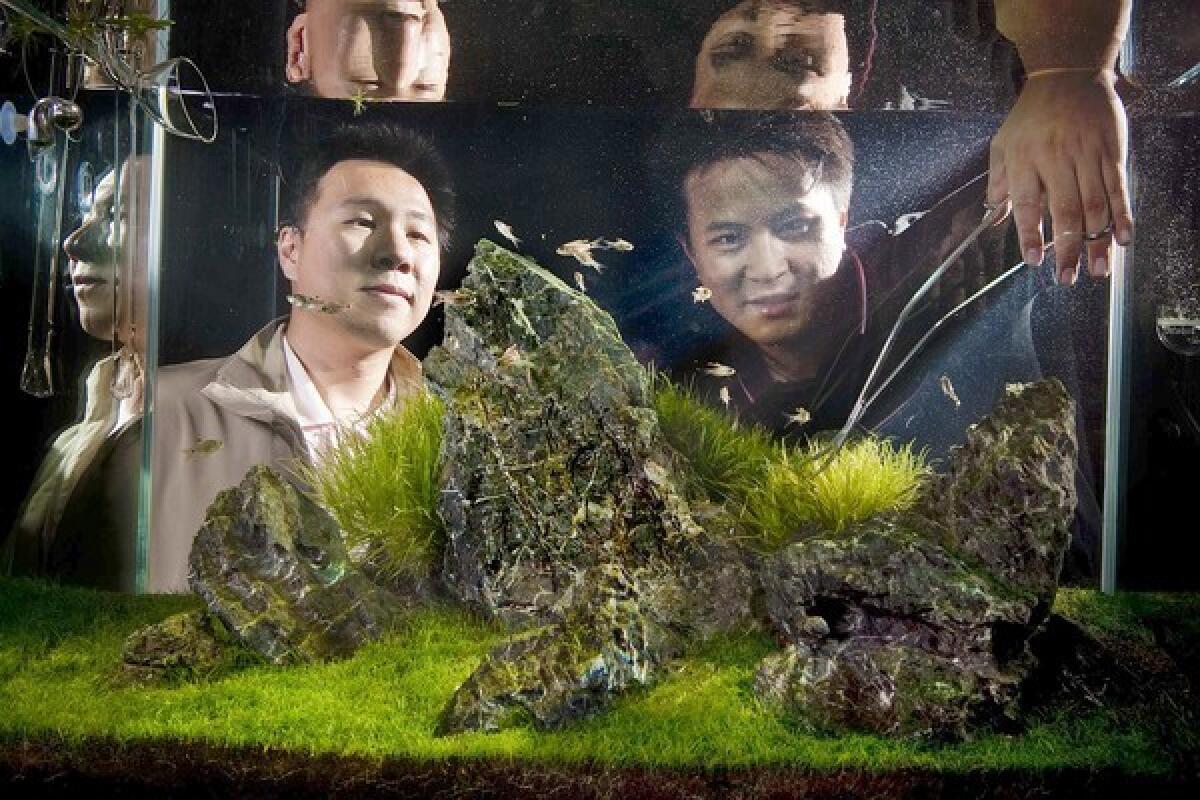

In the display tanks of Aqua Forest Aquarium, there is no neon gravel, no miniature plastic castles, no sunken treasure boxes sprinkled with glitter. Instead, owners and brothers George and Steven Lo have created natural replicas of miniature underwater worlds: a branched piece of driftwood draped with dark green moss, a lush undulating fern-filled forest, a peaceful grassy meadow and, in a tiny 5 1/2 -gallon tank, a jewel box water-filled terrarium. Small fish and shrimp dot these environments, but like a flock of birds or grazing cattle in a landscape painting, they are only supporting characters. Here, the underwater plants get the attention.

On the still-transitioning part of Fillmore Street, a few blocks away from the boutique wood-oven pizza parlor and the Marc Jacobs store, Aqua Forest Aquarium is the first shop in the United States to specialize in the style known as “nature aquarium” -- the idea that rather than simply housing a colorful collection of fish, an aquarium should reflect the beauty, visual harmony and even tension of a wild landscape. Plants are the main element, but driftwood and stones are used as well to create a more natural feel. There are other types of planted aquariums, but this design philosophy was developed in the late ‘70s by Japanese nature photographer Takashi Amano, whom George Lo describes as “like a god.”

Nature aquariums are more popular in Asia, but the trend is taking root in the U.S. The movement owes its existence to Amano, who has put out four lavish books about freshwater aquascaping. He began experimenting with aquariums in his early 20s, inspired by a boyhood playing in the Yoroi wetlands in Japan and later during trips to tropical rain forests in the Amazon, West Africa and Borneo.

“When I swam in the river, I found many aquatic plants flourishing and fish swimming in schools,” he wrote in an e-mail. “Here the plants are the place for spawning, and hiding place for fish.” Underwater, he found a world where plants turned sunlight into oxygen for fish, where nature found balance. “I wanted to create a space where plants and fish to coexist in a harmony inside an aquarium tank.”

Amano’s aquascapes are so dynamic and full of movement they look as if they are going to burst out of the tank. Sometimes they do. It is not uncommon for his plants, stones and driftwood to pop right out of the top by design.

“Based on my experiences, and exploration to tropical regions, I believe my layout is getting close to the image of nature and natural habitat,” Amano said. “In a sense, the layout looks more natural than nature, I think.”

Last year George Lo placed 20th in an international competition sponsored by Amano’s aquascaping company, ADA. No fewer than 1,342 people from 51 countries submitted photographs of their aquascapes.

George Lo’s tank -- the only American entry to place in the top 30 -- was a 170-gallon scene of serenity. A delicate carpet of clover rolled across the foreground as tufts of soft grass rose gently in the background. A thoughtful arrangement of gray stone slabs anchored the green, and a school of small blue and red cardinal tetra fish floated above it all. George Lo said the iwagumi design, based on a Japanese rock garden layout, took him more than a year to perfect.

He spent weeks on the placement of the stones alone. He wanted them to look as though they had been tossed in a riverbed, resting at the most stable positions. But they were heavy and difficult to move, and if he had dropped one, it could have cracked his tank. He also had trouble making sure the clover filled out along the bottom correctly. It kept getting leggy.

“It is kind of stressful to design a tank,” he said. “They are always changing, and with these tanks you won’t know how it looks until the plants start to grow out.”

::

For some, the home aquarium may conjure images of children trying out their pet-raising training wheels or a bored bachelor over-investing in tropical fish, but the planted aquarium has been gaining a U.S. following. Karen Randall, who sits on the board of the Aquatic Gardener’s Assn., began getting serious about growing plants in her aquariums in the mid-1980s but had trouble back then finding a store that sold a variety of liveplants. Even if an aquarium owner could find underwater plants, Randall said, information on how to take care of them was limited.

The rise of the Internet, however, has changed all that. Finding fellow underwater plant enthusiasts and sharing advice became a lot easier, even on an international level.

“Europe was kind of ahead of the U.S. in terms of plant selection and how to best keep them alive,” Randall said.

By 1991, the Aquatic Gardeners Assn. put out a magazine for 300 aquascapers, who met mostly through online message boards. Since then the number of subscriptions to the quarterly publication has quadrupled to a current high of 1,200. At their last bi-annual conference in Atlanta, 150 aquascapers attended lectures on tissue grafting and watched an “iron man aquascaping challenge” in which two people were each given one tank and one hour to aquascape it.

Amano’s books have been translated into six languages, and he lectures and holds workshops throughout the world. His company creates and sells high-end aquascaping tools, making him the authority not only on how these underwater gardens are designed, but also on how they’re tended (with near-surgical precision).

His aquariums borrow ideas from Japanese flower arranging, Zen rock arrangements and the idea of wabi-sabi -- that imperfect is beautiful. “It is important the tank doesn’t look too symmetrical,” Steven Lo said. “There is a lack of dynamic tension.”

Randall, who served as a judge for this year’s ADA contest, said she looked for “a balance in the layout, that the plants make sense in terms of sizes and colors, as well as textures and shades.” And the fish matter too. They should complement the planted waterscape and avoid what Randall calls the “Noah’s Ark mentality -- two of everything.”

::

The Lo brothers, two of a handful of people in the world who have a certificate of completion for their studies with Amano, did not compete in the ADA contest this year because they’ve been too busy with Aqua Forest Aquarium. Business has been growing.

On a recent afternoon their small storefront was filled with an assortment of customers: two heavy-set men obsessing over what fern plants to buy, three middle-school kids just looking around, a mother of two buying fish for her son’s tank.

“It wasn’t until I came here that I realized how much more you can do with an aquarium,” said David Herzenberg, a 28-year-old aquarium enthusiast who kept his girlfriend waiting two hours while he examined the plant-filled tanks at Aqua Forest. “It makes more sense to have a real ecosystem in there.”

The Lo brothers said the people at their store are a mix of foot traffic and serious aquascaping hobbyists who come specifically for their selection of plants and the Amano tools.

“The first time I walked in here I thought, ‘This is not an ordinary aquarium shop,’ ” said Kendric Lum, a resident of nearby Pacifica and a regular at Aqua Forest. “It used to be that when I think aquarium, I think fish. But I feel like you have to be a botanist to come in here.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.