Dealing with depression in seniors

After my mom died, I temporarily moved back in with my 81-year-old dad. My parents had been married more than 50 years; the last five had been difficult. Mom had a host of serious problems, including dementia. Taking care of her had left my father with his own health problems. I wanted to see how he’d do on his own.

Every day when I left for work, dad walked me out to the car and said, “Anything you want done today?”

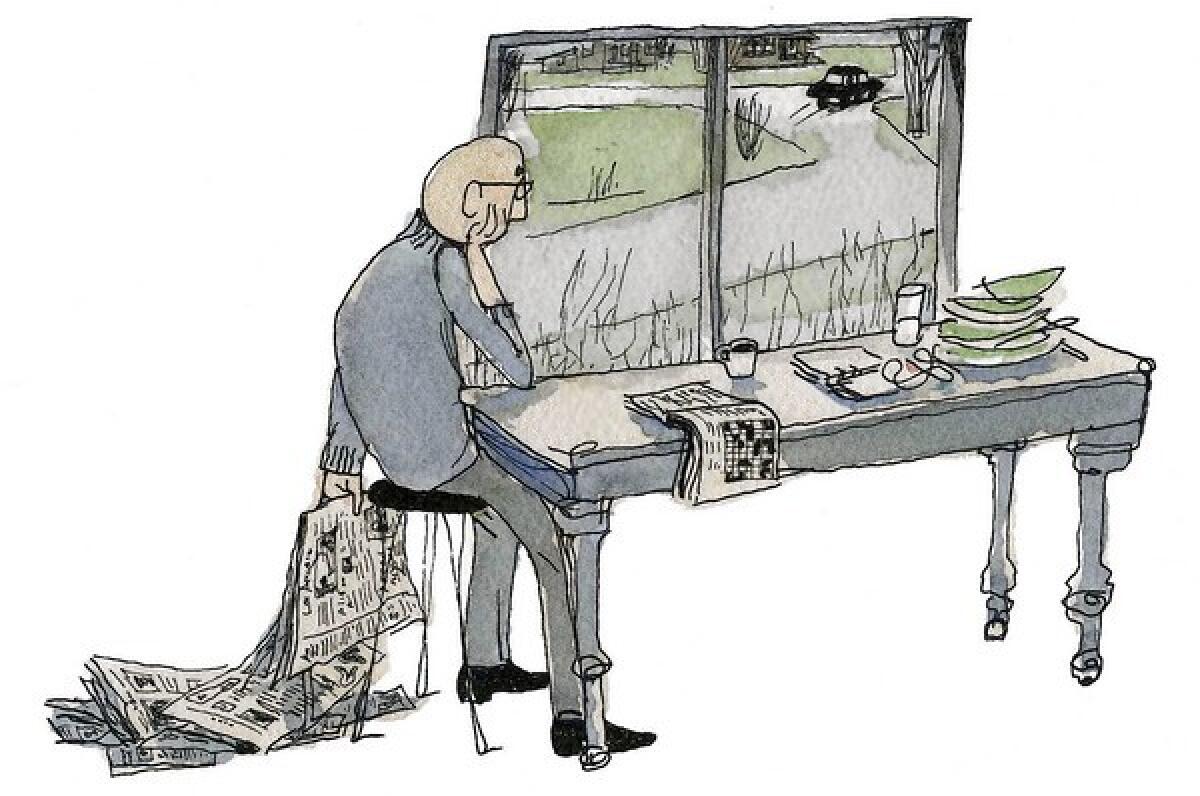

I rarely had any tasks for him. As I drove away, I could see him in my rearview mirror bleakly watching my car disappear. I’m sure the day ahead of him seemed long and empty.

In retrospect, I realize he probably was suffering from depression. But even if I’d recognized the symptoms at the time, I may have reacted the way many adult children do: I would have thought, “Of course, he’s depressed. He has a lot to be depressed about; his health is failing and mom just died.”

Increasingly, health professionals are recognizing that depression among older adults is a serious problem that needs to be treated. They’re also recognizing that adult children are often oblivious.

“Younger people, including younger medical personnel, often don’t notice it,” says psychologist Bob G. Knight, associate dean at the Andrus Gerontology Center at USC. “When they do, it doesn’t surprise them. They think: ‘They ought to be depressed, they’re old.’ So instead of helping the person deal with it, they ignore it.”

But depression isn’t normal at any age, experts say. Most older people are satisfied with their lives, even when confronted with health problems or the loss of friends or a spouse. They grieve, but they bounce back.

Those who don’t — the ones who continue to feel sad for weeks or months — often suffer from depression. They account for as many as one-fifth of the population of older adults in the United States. Untreated, the disease can lead to alcoholism, prescription drug abuse and illness. It’s partially blamed for the fact that seniors have the highest suicide rate of any age group in the U.S., experts say.

Experts say the following are signs that a person might be depressed. Some of these symptoms also could indicate serious illness and should be checked by a doctor. A general practitioner is a good place to start.

•Feelings of emptiness, worthlessness or feeling unloved.

•Lack of interest in doing things the person once enjoyed.

•Feeling nervous, restless, irritable.

•Feeling like life doesn’t seem worth living.

•Eating or sleeping more or less than usual.

•Feeling tired and sluggish.

•Complaining of headaches or stomachaches.

Despite the prevalence of the problem, few people get the help they need.

“Depression is under-diagnosed and under-treated,” says Dr. Laura Mosqueda, head of UC Irvine’s geriatrics program. Doctors tend to focus on physical complaints, and patients don’t help; they’re often reluctant to talk about their feelings or to ask for help.

When dealing with her older patients, Mosqueda tries to avoid using the term depression — or any others that might indicate a mental problem. People in their 70s, 80s and 90s are intimidated by those words, she says.

“I’ll say to them, ‘This low mood is something we can help you with.’ And I often talk to them about coping and tell them they might feel a whole lot better if they get help.”

Adult children can use the same tack when trying to help their parents.

“Have a dialogue with them,” says Joseph A. Weber, coordinator of the Gerontology Academic Program at Cal State Fullerton. “Ask how they’re feeling, how their mood is, what’s going on with their lives.”

And pay attention to other indications in the home that something might be wrong. Check the refrigerator and pantry to see whether they’re stocked. Is the house dirty when it once was clean? Are they neglecting the lawn or other chores that they once liked to do? Are they neglecting their own hygiene?

Weber says another clue is their isolation. “If you find they’ve become reluctant to go out, that’s a problem. They may say something like, ‘All I feel like doing today is reading the paper.’”

Antidepressant medications can ease the symptoms of depression, but some studies show that therapy works just as well, and without the safety concerns medication can pose.

Weber suggests children work with parents to find solutions. Set up regular visits, shopping trips, opportunities to see grandchildren, visits to the library or cinema.

“Everyone needs something to look forward to,” Weber says.

At the same time, don’t exacerbate the problem by becoming too pushy.

“A lot of older adults struggle with accepting help; they don’t want to be a burden to their children,” says UC Irvine neuropsychologist Mina Oak. “Remember that your parent is not a child and doesn’t want to be treated like one.” Children need to avoid sending a message that, “You can’t take care of yourself anymore, so I’m going to take care of things for you,” Oak says.

The best way to find a solution is to do it together. At the same time, try to find new ways to nurture the relationship, she says. And remember to appreciate and value parental advice.

“No one wants to feel like a burden,” says Oak. “They want to feel like they’re contributing and are involved.”

My dad eventually worked his way through his bout of depression. He started attending art classes and joined a senior club, where he went dancing a couple of times a week. But it took almost a year for him to start enjoying life again. I’m sure it would have helped if I’d recognized the problem and encouraged him to talk to his doctor about it.

With treatment and support from those who love them, people can feel better, doctors say. No one has to live with depression.

Comments: home@latimes.com

McClure’s column on caring for and staying connected with aging parents appears monthly.