An unlikely witness provides one last hope for soldier in murder case

- Share via

Second Of Two Parts — At the Dillard’s counter in Oklahoma City, Vicki Behenna was buying a beachy canvas purse for summer when her oldest son called from Iraq.

“Mom.”

“Hey Mike, how are you doing?” she asked. She was relieved to hear his voice, but quickly sensed the strain in it.

FOR THE RECORD:

A killing in Iraq: An article in Monday’s Section A about the trial of Army 1st Lt. Michael Behenna, who shot an unarmed Iraqi, misstated the age of bloodstain expert Herbert MacDonell as 88. He is 81. —

When the connection failed, she kept the phone in her hand, waiting. In the last few weeks, she had been desperately worried about him.

Michael Behenna, 25, was an Army lieutenant leading an infantry platoon on his first tour in Iraq. He had just been home to Oklahoma for a three-week leave. He was distant and withdrawn, tormented by a roadside bomb that killed two of his soldiers.

His family tried to get Michael out to reengage in his old world. They went horseback riding in the Arbuckle Mountains, hosted game nights of Scattergories and Pictionary. None of it could get him out of the storm in his mind.

In the mall during that visit, his younger brother Brett asked him a question about his platoon. Michael didn’t say anything. His lips tightened and his eyes teared up. Brett had never seen him cry. He quickly put his arm around Michael’s shoulder and pulled him in close so other shoppers couldn’t see him. Michael struggled to say something but couldn’t. He fumbled to get sunglasses out of his pocket. His mom and girlfriend rushed over, and they walked to Vicki’s car, where he wept inside alone.

Now Vicki’s phone rang again, and she rushed into the open mall to hear him better. Children’s laughter from the play area resounded from the floor below. She could barely make out his words -- something about him being removed from his base, an investigation.

“An investigation on what?” Vicki asked.

He told her it was about the death of an Iraqi. “If they just know what happened out there it will be OK,” he said.

Vicki Behenna was a 20-year federal prosecutor. As a mother, she wanted to hear every detail. But the attorney in her knew that he had to stop talking. If he made some terrible admission, there was no legal privilege protecting her from being called to testify.

“Don’t tell me anything,” she said.

For the next few weeks, in June 2008, Vicki and her husband, Scott, an FBI intelligence analyst, could barely eat or talk. They couldn’t ask questions or get facts.

Vicki needed to see for herself how Michael was doing. She knew he needed counseling. He had tamped so much down. If only he could come home.

A dread took root like a tumor in her gut, a fear of what he might do to himself. She wouldn’t form the words to give it currency. But it was there, swelling, finding resonance in the heavy hopelessness of his voice.

She asked if he was still working out at the gym.

“The person I worked out with is no longer here,” he said. “I can’t go back there.”

His weight-lifting partner, Adam Kohlhaas, had been killed in the attack.

“Are you sleeping, Michael?”

“No. I’m not.”

On July 31, 2008, Behenna was charged with premeditated murder, assault and making a false official statement in the killing of an Iraqi detainee named Ali Mansur Mohamed. A conviction on the charges would carry an automatic life sentence.

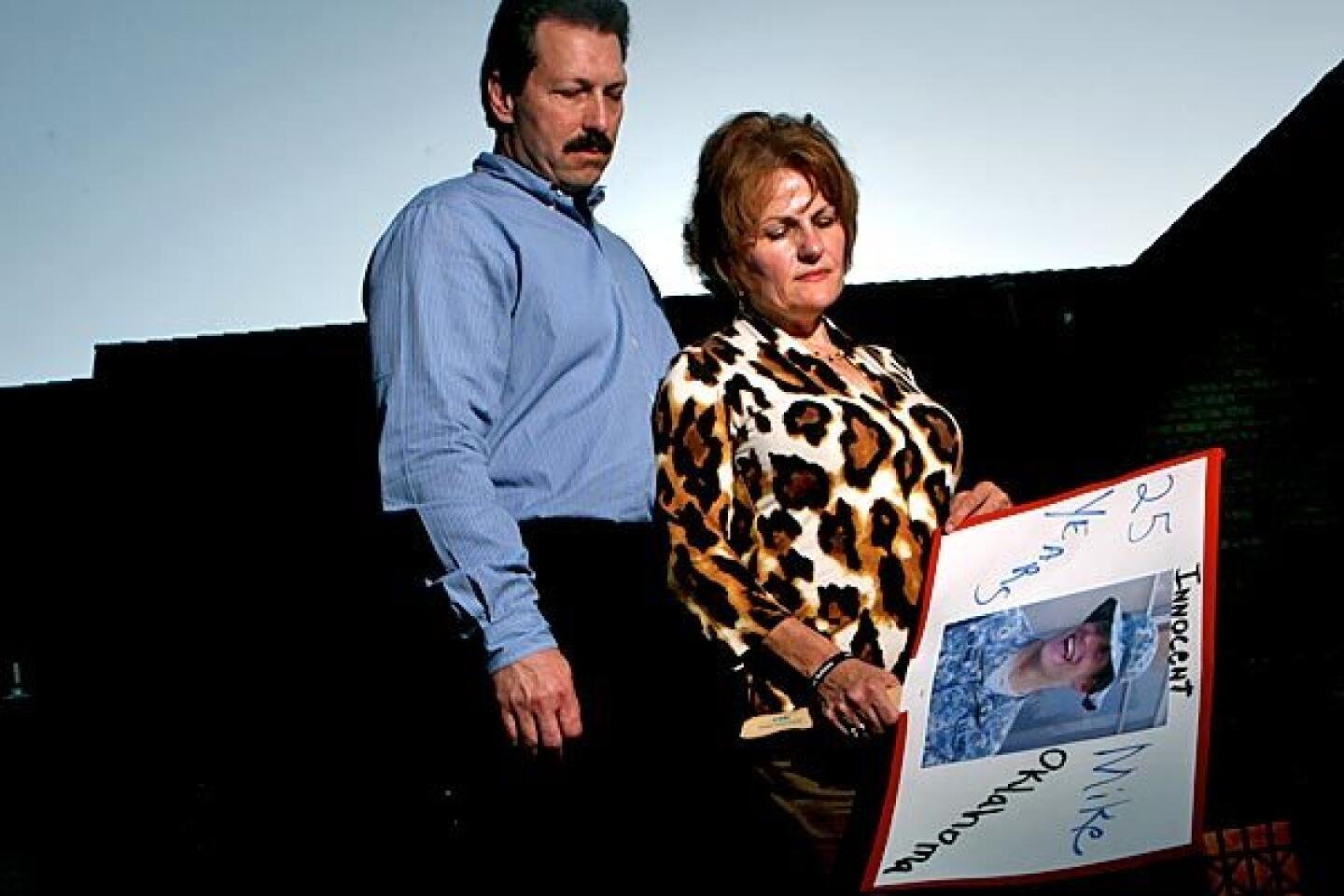

Television news crews pulled up outside the Behenna home in Edmond. Scott and Vicki were well known in local law enforcement circles: Scott, a 25-year veteran of the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation, had been shot in the head during a shootout with a fugitive in 1987. Vicki was part of the seven-person team that prosecuted Timothy McVeigh.

The Behennas holed up inside, praying, trying just to breathe. They still didn’t know what happened.

In bed at night, Vicki’s mind lashed about in the vacuum. Was it really Michael? Maybe it was someone else. Maybe it was self-defense. Maybe it was an accident. He wouldn’t just kill someone in cold blood.

She knew her son. But she knew how disturbed he was too.

She always cycled back to that dread.

The Behennas talked to dozens of attorneys and hired Jack Zimmerman, a former Marine Corps trial judge and Vietnam vet with two Bronze Stars.

After an Article 32 hearing, the military equivalent of a grand jury proceeding, details emerged in the news. The dead man was an unarmed detainee. His body was found in a culvert, naked, shot in the chest and head, partially burned.

Vicki’s inner-mother tried to stifle the inner-prosecutor. She clung to what he had said: “If they just know what happened out there.”

She trusted him. But those scant words looked awfully rickety under the weight of the allegations. Why did he take him out in the desert in handcuffs? she thought. Why did he strip him? Why did they burn the body?

Vicki called Zimmerman, wondering if they should try for a plea deal. He assured her that Michael had a plausible defense.

Michael returned to Ft. Campbell, Ky., in November, and the Behennas could at least breathe again. When Michael’s major put him on the team coordinating security for an upcoming visit by President Bush, they took this as a hopeful sign. Would the Army command put someone they thought was a murderer on the president’s security detail?

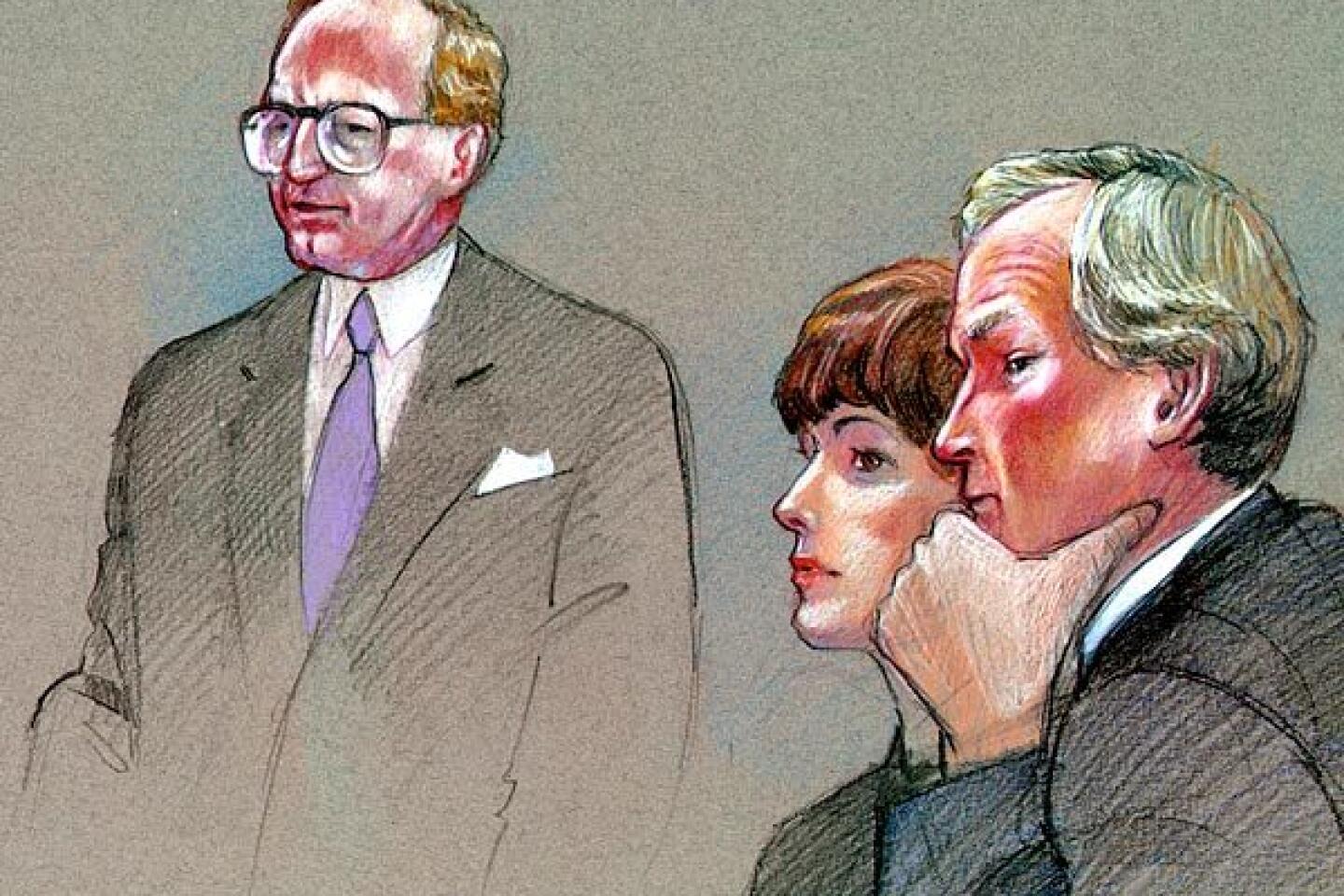

On Feb. 23, 2009, Capt. Erwin Roberts made the prosecution’s opening statement before a panel of seven officers. The court-martial would follow rules similar to those for federal criminal trials.

Roberts described a cold, straightforward execution.

“The evidence will show that on 16 May 2008, the accused took the victim out into the desert in Iraq, stripped him naked, interrogated him while he had his Glock pistol pointed at him, shot him in the head, shot him in the chest, killing him at that time,” he said.

He said this was an act of simple vengeance: Behenna thought Mansur had played a role in the attack that killed his two soldiers and wounded two others. When he detained him, he beat him with his Kevlar helmet before handing him over to intelligence specialists for interrogation. Ten days later, when the order came down from higher command to release Mansur, Behenna was infuriated. He took him out, killed him and then ordered a sergeant to burn the body.

Zimmerman wouldn’t dispute some of the circumstances, even that Behenna shot Mansur.

He would dispute the intent.

Zimmerman depicted a young man near his breaking point, sleepless and haunted by ghastly images, who hatched a misguided plan to scare a suspected insurgent into talking.

“He knew from a source in his area of operations that Ali [Mansur] had been identified as a terrorist,” Zimmerman said in his opening statement. “You are going to see a . . . Draft Intelligence Information Report prepared by Army intelligence sources that reported Ali was a supplier of explosives and weapons and was [in the report] that describes the Al Qaeda cell that detonated that IED [improvised explosive device] on the 21st of April.”

When Behenna arrested Mansur, he hoped he had removed a deadly adversary, Zimmerman said. Then when word came down to free Mansur, Behenna learned that Army interrogators had just asked him about an illegal gun -- not the insurgent cell.

“So, Lt. Behenna decided that he wanted one more opportunity to learn who the big fish were in this area,” Zimmerman said.

No question that Behenna disobeyed orders, the attorney said. He threatened to kill Mansur. He dragged him out into the desert, stripped him, removed his blindfold and handcuffs and pointed his gun at him.

The critical difference would come down to a single second in that dark culvert.

Who could see what happened besides Behenna and the dead man? Was this an execution, or did something cause Behenna to act in self-defense?

The government’s key witness was “Harry,” an interpreter, who accompanied him to the culvert.

“Did Lt. Behenna ask you to tell Ali Mansur anything?” asked Capt. Meghan Poirier, the lead prosecutor.

“Yes. . . . ‘What do you know? What groups do you know?’ ” Harry said. “And I told him, ‘Talk to me today because if you don’t talk, I will kill you.’ . . . First he denied and then the second time he said, ‘I will talk.’ I started to interpret to the lieutenant that Ali Mansur is going to talk.

“At that time the lieutenant shot a bullet,” he said.

“Did you see Ali Mansur make any sudden movements?” the prosecutor asked.

“No.”

“And did Ali Mansur remain seated on that rock?”

“Yes, he was sitting.”

“What happened after the first shot?”

“He was kind of falling, and then he just laid on his side. While he was making this movement came the second shot.”

On cross-examination, Zimmerman asked whether it “was standard practice to try to scare detainees into giving information.”

“Yes,” Harry said.

“You didn’t think that Lt. Behenna was going to actually kill him, you thought that was a scare tactic.”

“Yes, just scaring him.”

Zimmerman asked him what the local sheik meant when he said Mansur was a “bad person.”

“Terrorist operations, information, everything,” Harry said. “A bad person who would place explosives, he would kill, he would kidnap.”

Zimmerman turned the questioning back to the culvert.

“You didn’t see what happened before the gunshot happened?”

“No, I didn’t see exactly.”

As witnesses came and went, the picture remained blurry in spots.

Staff Sgt. Hal Warner testified that Behenna had ordered him to bring an incendiary grenade with them into the desert -- implying the killing was planned. But Harry and another witness said they didn’t hear this. Warner had been charged with murder too, but the charge had been dismissed in exchange for his testimony. The defense grilled him about the plea deal, a false declaration he had made about the killing and inconsistencies in his statements.

Still, the core fact remained: Behenna shot a naked, unarmed man in his custody.

Only he could explain how this was not an execution.

First the defense would lay groundwork. Dr. Paul Radelat, a Houston pathologist, testified that the bullet trajectories suggested Mansur was standing up with his arm raised when he was shot. Tom Bevel, a crime scene specialist and 27-year veteran of the Oklahoma City Police Department, said Behenna and Mansur were “in a confrontational body position . . . like two boxers in a boxing match.”

A psychiatrist testified that Behenna suffered from acute stress disorder after his men were killed, and that molestation he suffered as a youth predisposed him to it. This could cause him to overreact to a scare.

The pivotal role, however, would be played by the most unexpected of actors.

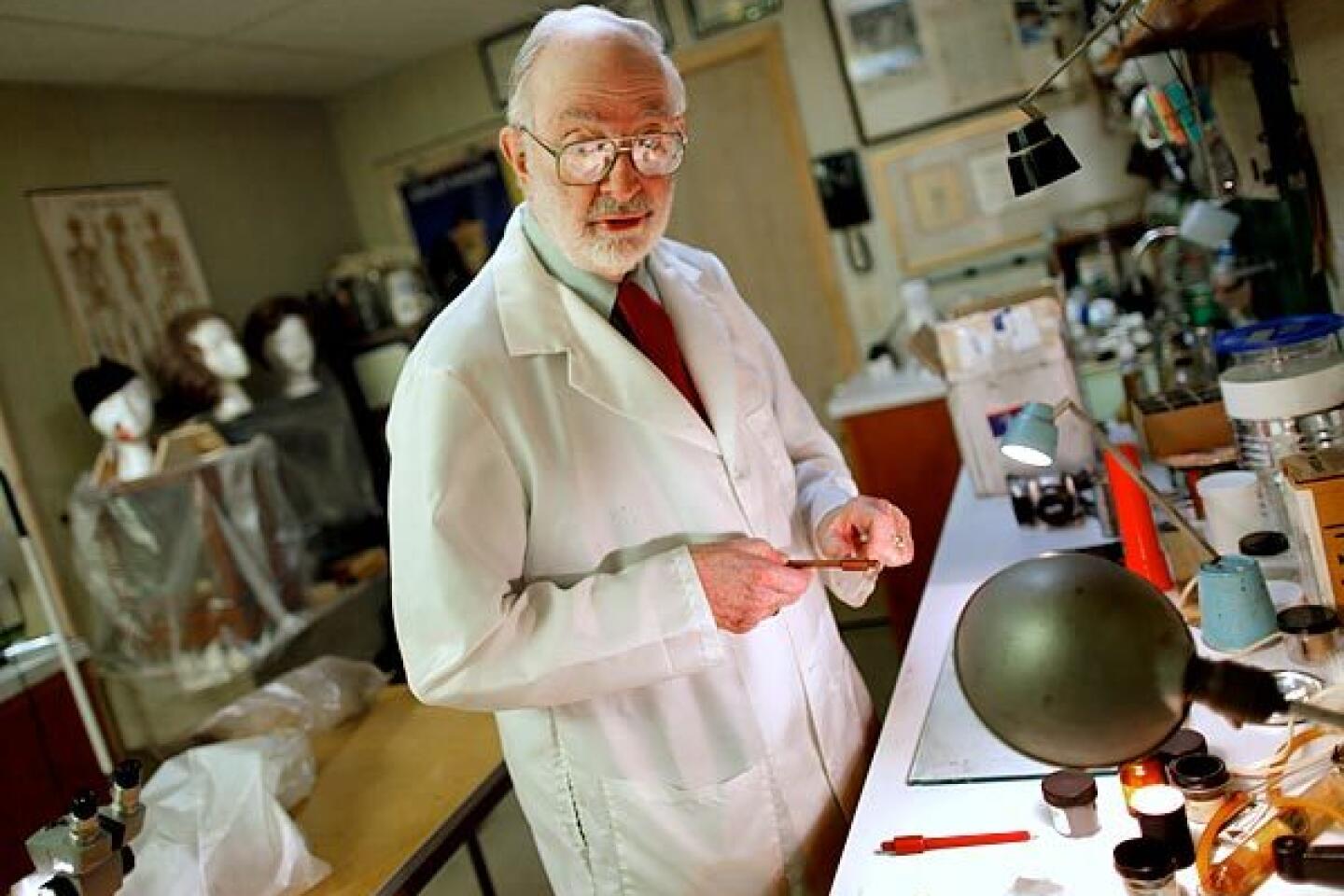

Herbert MacDonell, a pioneer in the field of bloodstain pattern analysis, was hired by the prosecution.

MacDonell, 88, listened to the testimony from the gallery and had trouble with his clients’ theory. With the two bullets traveling through Mansur’s body on horizontal paths, and the resulting bloodstain pattern, he could not see how the victim could have been seated when he was shot, with Behenna standing over him, as prosecutors contended.

MacDonell also noticed that the single bullet recovered from the scene had been pancaked flat, as if it had hit a wall head-on.

MacDonell would later say he told prosecutors there was one logical explanation: Mansur, standing up, with his arm out, was shot first through the chest. As he fell, the second bullet hit his head as it passed down in front of the gun. MacDonell demonstrated on a paralegal, pointing his finger as a gun, and having him drop. “Bang. Bang.” The bullets would cut horizontally through Mansur and hit the culvert wall.

The question then was: Why would Mansur have been standing up with his arm out?

The next day MacDonell watched as Behenna took the stand. Scott and Vicki barely noticed the old man to their left.

Behenna was asked what he had planned to do with Mansur. “My intent on May 16 was to question Ali myself,” he said. “I knew he had information about the April 21 attack. I knew he knew who the cell leaders were. . . .”

Behenna said he grabbed Harry and took Mansur aside at the base. “I told him, ‘If I don’t get that information today, you will die today.’ ”

“Did you intend to kill him that day?” Zimmerman asked.

“No, sir.”

“Why did you have Harry tell him that?”

“To scare him.”

The Behennas studied his tone, his hands, his eyes -- like nervous parents at the school play of a child whose life depended on the performance.

They thought he was doing well, confident and clear.

MacDonell was more dubious. He knew that Behenna shot the man, after all. But he reserved judgment. Up to this point, no one but Behenna’s attorneys had heard his version of what happened in the culvert.

Zimmerman asked him why he cut Mansur’s clothes off.

“To humiliate Ali,” Behenna said. “A bad decision, yes. But I know in the Arab culture if another man is naked in front of another man, it’s humiliating. . . .” Behenna said he had Mansur’s civilian clothes in his cargo pocket and planned to give them to him once he gave information. He would point out the distant light of a highway checkpoint to guide him home.

Mansur was saying, “I don’t know,” in Arabic to his questions. Then he said something else. Behenna said he turned his head to the left to hear Harry’s translation.

“As I had my head turned toward the left, I hear a sound of a piece of broken concrete hitting concrete over my left shoulder,” he said. “Immediately, I turned toward my -- to my right . . . . Ali is getting up with his hands out toward my weapon. I stepped to the left and fired two shots.”

“Why did you step to the left?”

“To create distance from Ali.”

MacDonell was stunned. This made perfect sense to him and could explain why Mansur would have been standing with his arm out. “Maybe this guy’s telling the truth,” he thought. He tapped the shoulder of another prosecution consultant and whispered, “That’s exactly what I told you yesterday.”

MacDonell was to fly home to upstate New York that evening, after the prosecutors opted not to call him to the stand. On the way out, he told Zimmerman, “It’s too bad I am not testifying. I would have made a great witness for you.”

The next morning, Zimmerman told the Army lawyers about this cryptic remark and asked if they had anything to divulge. A key part of American jurisprudence, the Brady doctrine, calls for prosecutors to turn over evidence favorable to the defendant.

They said no.

That afternoon, MacDonell e-mailed the lead prosecutor.

“On Thursday afternoon when I heard Lt. Michael Behenna testify as to the circumstances of how the two shots were fired I could not believe how close it was to the scenario I had described to you on Wednesday. I am sure that had I testified I would have wanted to give my reenactment so the jury could have had the option of considering how well the defendant’s story fit the physical facts. This, of course, would not have been helpful to the prosecution case. However, I feel that it is quite important as possible exculpatory evidence so I hope that, in the interest of justice, you informed Mr. Zimmerman of my findings. It certainly appears like Brady material to me.”

The prosecutor would not get the e-mail until that evening. Meanwhile, the panel deliberated for less than 3 1/2 hours before coming to a verdict. The judge, Col. Theodore Dixon, asked a major on the panel to read the verdict aloud.

The flat tone and dry language gave the moment an air of routine bureaucracy.

“Of Charge 1 and its specifications: not guilty.” He beat the false declaration charge.

Then came the premeditated murder charge.

“Not guilty.”

“But guilty of the lesser-included offense of unpremeditated murder, in violation of Article 118, Uniform Code of Military Justice.”

This hit like a kiss and a stab in the neck. Behenna just stared. The maximum penalty was life in prison.

His parents and friends and aunts and uncles sifted out of the courtroom, red-faced, some sobbing.

In the car on their way back to their hotel, Vicki felt a sense of calm, a feeling this was going to be all right. Maybe it was a premonition, maybe it was an absurdity.

Michael was here, touchable. The details of his story added up, she would insist, leaving no nagging questions in her mind. She knew the variables now, and she knew her vantage as a mother.

They went to Michael’s apartment and found Brett and his girlfriend crying on the floor. Michael wouldn’t come out of the bathroom. The shower was running. Scott tried to get the door open. Vicki told Brett to pull himself together.

The shower stopped, and Michael stepped out and lay down on the bed. He wouldn’t let anyone touch him. He wouldn’t talk. He stared at the ceiling with tears streaming down his temples.

They tried to tell him his life was not over.

“When you get out, we’ll have a business going,” Scott said. “You can work for us.”

Eventually, Michael talked a little, and ate some food. “I’m a felon,” he kept saying. “I can’t vote. I can’t own a gun.” Vicki slept on his couch to keep an eye on him.

That night, prosecutors forwarded MacDonell’s e-mail to Zimmerman.

In court the next morning, Zimmerman immediately asked the judge for a mistrial. He said that MacDonell’s findings could have changed the verdict, and that prosecutors should have divulged them the moment they knew of them Wednesday afternoon.

“The Brady doctrine has been a topic I’ve taught,” Zimmerman told the judge, “and in 34 years of practicing, I’ve never seen a clearer Brady violation than this.”

Capt. Roberts said MacDonell never made a firm conclusion. “He never was certain about anything,” he said. “He was always just brainstorming and it was like he was still kind of experimenting.”

The court phoned MacDonell. He reiterated what he wrote in the e-mail. But he couldn’t hear well over the phone and his testimony was confusing in regard to how definitively he had conveyed his findings to the prosecutors.

The judge told both sides to write briefs for a later hearing.

Vicki watched in disbelief. For her, MacDonell’s e-mail was nothing short of divine intervention. She whirled so furiously between anger and elation that she left to vomit in the bathroom.

Just before 5 p.m., the members announced the sentence: 25 years in Ft. Leavenworth.

“Twenty-five years?” Michael repeated. “I’ll be 50 when I get out.”

Three weeks later, Dixon denied the mistrial motion, saying MacDonell’s testimony wouldn’t have changed the verdict. He said an affidavit MacDonell signed, saying exactly what he told prosecutors and when, was not credible.

This ruling, on March 20, had the thud of finality. Vicki’s throat and chest tightened.

She and Scott tried to console Michael. He tried to console them. She wondered what she could have done differently.

Why did she encourage him to join the ROTC? Why did she say serving his country was honorable? Why couldn’t she have protected him when her father was abusing him as a child?

An officer came with handcuffs to take Michael away.

“Everybody is going to forget about this, aren’t they Mom?” Michael asked.

“As long as there is breath in me, I’ll tell your story,” Vicki said.

She walked out front to see the van take him away. She wanted to wave, but thought he’d be embarrassed -- as if he were still just a boy, on the bus to summer camp. For the first time, she broke down completely.

In June, 25 prominent Oklahoma attorneys wrote the Secretary of the Army calling the trial “a miscarriage of justice” and demanding a new one. They said “it is rank speculation to pretend that even an experienced jurist can know how the court members could react to this startling fact -- that the government’s own expert, renowned in the field of forensics, concluded the defense’s theory of the case was ‘the only logical explanation of this shooting.’ ”

Army officials have declined to comment but have said in court that they divulged everything they knew, and that MacDonell’s testimony would have been insignificant.

Vicki and Scott want the Army command to answer for the whole chain of events.

Why did they have Michael return Mansur that day, knowing that he thought this was the man behind the killing of his soldiers?

And why -- amid all the bloodshed and civilian death -- did they prosecute this case as premeditated murder?

In July, the court-martial authority reduced the sentence to 20 years. The difference is an abstraction now, as Behenna is learning to navigate the vagaries of Ft. Leavenworth.

His parents make the five-hour drive north every weekend. They hired Zimmerman for the appeal, and are getting help from a law professor at the University of Oklahoma.

Vicki thanks God for an 88-year-old man she never met. MacDonell’s last-minute e-mail has kept the future from slamming shut. Her voice catches when she speaks of him.

“If he didn’t send that e-mail we would have no hope in the world,” she says. “We would have nothing.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.