From the Archives: Aerospace legend Simon Ramo looks back at the time he wasted — in meetings

- Share via

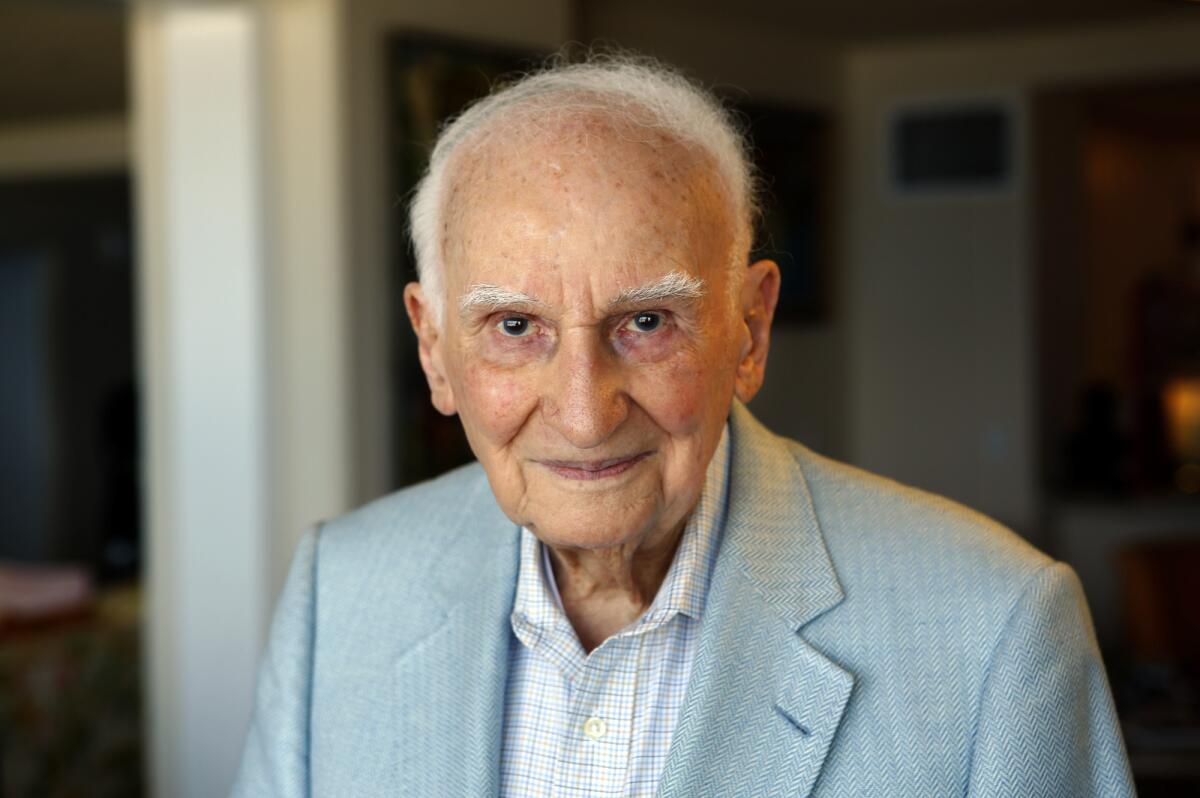

In this Los Angeles Times article from Nov. 15, 2005, Simon Ramo discusses the publication of his 15th book. Ramo died Monday at 103.

During his 69 years in the aerospace industry, Simon Ramo figures he’s attended more than 40,000 meetings -- an average of two or three per workday.

About 30,000 of those meetings could have been shorter or not held at all, he laments.

Ramo, the 92-year-old co-founder of TRW Inc., can never reclaim those thousands of “lost” hours, but he hopes he can save other managers from the same fate with his 15th book, published last month: “Meetings, Meetings, and More Meetings: Getting Things Done When People Are Involved.”

“There are all kinds of gimmicks and books published about improving productivity, but half of our time is spent in meetings,” he said in an interview. “If done better you can get the time spent in meetings down by half. Now we’re talking about a big impact on productivity.”

Half a century ago he co-founded TRW -- he was the “R” -- and then at the age of 89 brokered the sale of the company to Northrop Grumman Corp. He could easily sit on his laurels at his seven-acre estate in Beverly Hills, but 27 years after “retiring” from TRW’s board he remains hard at work.

The book is the latest effort for a very active nonagenarian who continues to be a player in the aerospace industry.

Each workday, Ramo puts on a suit and tie and drives himself to his West Hollywood office at 8:30 a.m. He spends mornings working the phones, then goes to the Four Seasons Hotel in Beverly Hills, where he’ll have lunch with key industry officials.

Lunch often finds Ramo -- constantly interrupted by “Hi Si” greetings from fellow diners -- brainstorming grandiose ideas about aerospace with a young executive. On a recent day, Gerald S. Levey, dean of UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine, dropped by to congratulate Ramo on his latest book.

Ramo remains a senior consultant to Northrop and he meets regularly with Chief Executive Ronald D. Sugar to go over strategic ideas concerning the nation’s third-biggest defense contractor.

“He is still very active and very well-connected,” Sugar said. “I talk for about five minutes and then he gives me his thoughts on subjects that I was already thinking about or should be thinking about. What is remarkable is how clearly he understands what is going on.”

A conversation with Ramo always has a specific purpose, acquaintances say. There is little small talk, even with longtime friends, and Ramo rarely deviates from a particular subject on his mind.

“Most of the time, he gets together with me ... when he thinks I ought to know something or I ought to meet someone,” Levey said.

Most of the time, he gets together with me ... when he thinks I ought to know something or I ought to meet someone.

— Gerald S. Levey, dean of UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine

Ramo, who made his mark during the Cold War as the chief architect of America’s intercontinental ballistic missile system, remains an avid student of international affairs.

In recent months he has been reading up on China, mainly because he feels the U.S. geopolitical focus will shift to the Pacific, as China’s influence in the region grows both economically and militarily. The move will entail a buildup of nontraditional Navy ships, he said, declining to elaborate. Northrop is the nation’s largest military shipbuilder.

He also foresees a major change in the Pentagon’s approach to dealing with terrorism and nuclear proliferation, but feels that the military has done a poor job of spelling out its needs. That uncertainty will pose a big problem for the defense industry, he says.

Planning for the nation’s defense is “more puzzling and more difficult than I have ever seen,” Ramo said, adding that the situation also would create new opportunities for “creative and imaginative” defense companies.

Ramo’s influence extends to decision makers in education, research and culture, Sugar said. Ramo has regular conversations with R. James Woolsey, a former CIA director and now a vice president of consulting firm Booz Allen Hamilton Inc.; Steven Sample, president of USC; and John E. Bryson, chairman of Edison International.

The native of Salt Lake City was an aspiring concert violinist when he heard legendary violinist Jascha Heifetz. At that moment, Ramo decided not “to be a concert violinist.” Ramo and Heifetz became friends years later and even played a duet together once at a dinner party.

Ramo changed his focus to science, earning a doctoral degree in electrical engineering from Caltech in 1936 at age 23. That year he began working on military-related programs for General Electric Co., where he also helped develop the electron microscope.

After World War II, Ramo moved to Hughes Aircraft Co., then Howard Hughes’ airplane company in Culver City, to launch a division devoted to military electronics.

Ramo went to work for Hughes because he knew that one of the richest men at the time spent little time overseeing the company. When he did show up, Ramo recalled, Hughes would “toss off” detailed directions, for example, about what kind of seat covers to buy for company-owned Chevrolets.

“He was a nut,” Ramo said.

Ramo left in 1953 and formed what became the predecessor to TRW after the Defense Department grew wary about contracting sensitive military work to the eccentric Hughes. That same year, the Eisenhower administration bypassed big defense contractors and asked Ramo to lead the development of the intercontinental ballistic missile.

It was during the missile’s development that Ramo became legendary for capsulizing complex ideas into off-the-cuff witticisms.

When the United States’ first ballistic missile rose about 6 inches above the launch pad before toppling over and exploding, Ramo turned to an Air Force general and said: “Well, Benny, now that we know the thing can fly, all we have to do is improve its range a bit.”

The same kind of wry observations show up in Ramo’s latest book: “How can you help abolish unnecessary meetings? One way is not to go to them. You can’t pull that off every time, of course, because you may get fired.”

Ramo said wasteful meetings had irked him all his life. He began making mental notes about the annoyance throughout his career. The book is filled with numerous real-life examples based on actual people Ramo encountered over the years, although “the names have been altered for the usual reasons,” Ramo said.

In the book, Ramo writes about “Hawkins,” a chairman of an unnamed charity who called for so many “special meetings” whenever there was a problem that it drove Ramo to resign from the board. Or an executive at an aerospace company who kept standing in front of the projector so no one could see the presentation.

And then there were those who made ill-fated attempts at doing away with meetings, such as “Eaton,” who skipped meetings called by his boss whenever he believed them unnecessary, including his last one, which the boss had called to talk about all the meetings he was missing.

Even good-intentioned efforts fell victim to bureaucracy. When “Lawrence” held a meeting to discuss ways of abolishing certain meetings, “we got into controversies about whether this or that particular meeting was truly essential or should be eliminated. The only way to settle it was to hold more meetings,” Ramo said.

Throughout the book, Ramo provides insightful advice when meetings are unavoidable: For dozers, who can’t stay awake, “pinch your cheek and your thigh frequently.” For those who “sweat profusely, cover yourself with a very lightweight jacket. (You’ll perspire more, but fewer will notice.)”

“I never try to be humorous or funny,” Ramo said. “It just comes out that way.”

Ramo’s 15 books cover various subjects. His first volume, on electromagnetic fields, has sold more than 1 million copies since it was published in 1944 and is still used by more than 100 universities. He also penned “Tennis by Machiavelli,” a book that applies the philosopher’s treatise on the wiles and strategy of running a nation to beating an opponent on the court.

Although Ramo has given up tennis and the violin, he has no intention of stopping writing. He’s finished another book and is planning to shop it to publishers soon. And he has another book in mind after that.

“I’ve thought about them for some time, but it’s just that I had other things that had priority,” Ramo said. “I’m now free to get to them.”

ALSO

Ikea recalls 29 million dressers after 6 children are killed

Airbnb sues San Francisco — its hometown — to block new rental law

Blue Shield faces new criticism of shortchanging consumers in California

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.