Milos Forman, Ivan Passer and their 73-year friendship: Childhood, escaping Czechoslovakia and conquering Hollywood

- Share via

So paralyzing was Milos Forman’s depression, Ivan Passer remembers, “he went to bed, refused to talk to anybody, would not pick up the phone. Would talk only to me. I would bring him food. And after three days, he stopped talking to me too.”

The two filmmakers were newly expatriated from Czechoslovakia and living in New York’s West Village. Milos, who’d lost both parents to Hitler’s death camps, had been prone to dark episodes since childhood. This one was complicated by a contract difficulty that left him owing Paramount $140,000 — an unfathomable sum in 1970 to the future director of “Amadeus” and “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

“I said, ‘Milos, this is not normal. We know each other since childhood. You have to go to a psychiatrist,’” Ivan said recently. “And Milos looked at me and said, ‘I’m not going to a psychiatrist. You should go to a psychiatrist.’

“I’m not quite sure why he said that, even today, but I thought, this is not such a bad idea.” So he went — as Milos Forman. “I would go and tell him what I thought Milos would. And he gave me pills, which I gave to Milos,” along with the doctor’s advice.

“How did you know I would say that?” Milos demanded at one point.

Said Ivan, “Milos, we’ve known each other a few Fridays.”

Within weeks, Milos was feeling better.

That they made it to America at all is a story worthy of a movie, among many tales Ivan tells from an uncommon and abiding friendship of two celebrated directors, one that spanned 73 years.

::

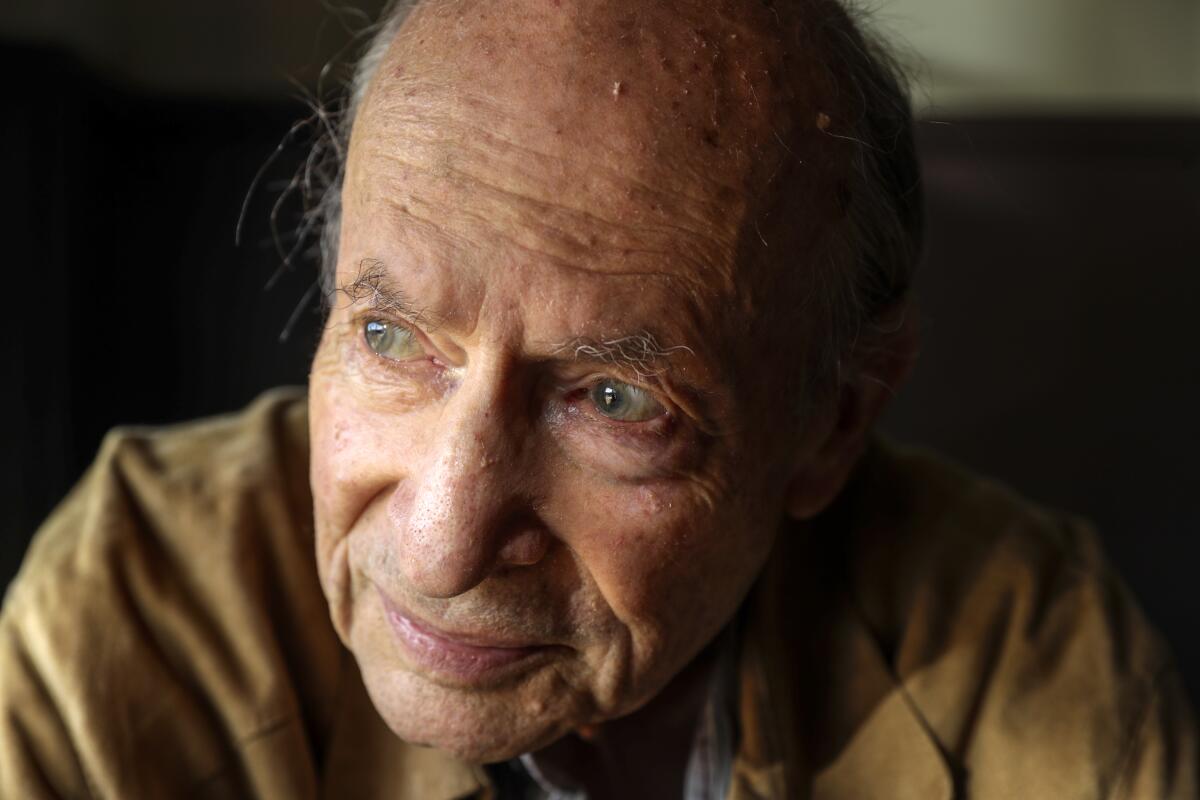

Settling in at a favorite window-side table at Hugo’s, near his longtime West Hollywood apartment, Ivan (EE-vahn) is unspooling detailed, discursive and hilarious narratives, which sound fresh though often told. At 86, the admired director of “Cutter’s Way” and the Robert Duvall epic “Stalin” is fit and animated, his benevolent face belying a razor wit.

In a Slavic accent still prominent, Ivan, a retired USC film professor, speaks the part of each character, building suspense and then springing a surprise, delighting in his listener’s reaction. The stories are never really about him, as if his part in these scenes was to recount them for our enjoyment.

On Ivan’s final visit to the psychiatrist, he confessed his deception. The doctor, absorbing the shock, asked, “What happened?”

“You cured him. He’s fine.”

Said the doctor: “You know, my wife loves his movies. Do you think we could meet him?” So a dinner was arranged for the couple, Milos Forman and his imposter.

Milos, meanwhile, soon received a telegram from Universal: It liked his script — the one that caused the Paramount predicament — which would become his first American movie, aptly titled, “Taking Off.”

The two friends’ arrival in New York followed a haphazard escape from Czechoslovakia a few months after the Soviet invasion of August 1968. They had figured they wouldn’t be gone long — until the absurd foreign intrusion was repelled, and sanity and liberty to their country restored.

But Ivan and Milos would never call their homeland home again. Their fellow filmmakers had to work as cabbies and postal workers.

It could easily have gone differently, says Ivan. They might’ve been blocked at the border, or stuck it out like the others. “And Milos might never have gone on to win two Academy Awards,” he says. “But destiny wanted otherwise.”

::

Asked about the first time he met Milos, Ivan’s eyes brighten and his smile is full of mischief. “I remember the first second I saw him!”

It was the early days after World War II, and 12-year-old Ivan had just arrived at boarding school, in a 13th century castle east of Prague. Suitcase in hand, he looked upon a courtyard where the boys were playing soccer.

Czechoslovakia owes its unfortunate history to its lot as a main stage for the great conflicts of the 20th century.

There ran Milos, he says, “the biggest of them all.” He charged through the pack, scattering others in his wake. “Already I knew it’s wrong,” says Ivan, laughing. “He was unsympathetic to me from the first moment, because he was plowing through all those kids.”

That was Milos: “He had to be the first in everything.”

Ivan, a year younger than the big kid, was a perennial malcontent with a defiant nonchalance. But he too enjoyed a contest. So when someone suggested a silly game — to pin the cap of your school uniform between your head and a brick wall the longest without using your hands — “I decided that Milos is not going to win this time.”

Hours later, they were the only two standing. “I don’t remember who won. All I remember is that I couldn’t move my neck [for days]. And Milos was impressed.” Soon they were jousting at billiards, ping-pong, tennis, swimming. “And we became friends.”

Their classmates included other precocious rebels, among them a future playwright, dissident and president of the future democratic Czechoslovakia, Vaclav Havel. Like most, Ivan and Milos had landed there by way of wartime miseries.

The Gestapo seized his stepfather when Milos was 8 — the only father he ever knew — and later his mother, both labeled anti-Nazi conspiracists. She perished at Auschwitz, he at Buchenwald.

Ivan too was 8 when the Germans came for his father, a Resistance activist deemed to have racial flaws; they sent him to a labor camp. Ivan’s mother, who’d joined a band of Slovak separatists in the mountains, was hounded to the edge of starvation. Ivan was cast adrift, often roaming the countryside with his hunting dog and found Russian army rifle.

Milos’ and Ivan’s experience under Nazi and, later, Stalinist rule inculcated a fire of moral insurrection — neither ever joined the Communist Party.

“To me,” said Czech American writer Jan Novak, their longtime friend and collaborator, “they are the true aristocracy.”

After boarding school, their paths diverged — Milos embarking on a theater career, Ivan again rambling the country, this time as a carny. But they soon met again, as students at the prestigious Prague Film Academy.

::

“How in this bloody country can you make a good movie?”

Milos’ question, put to fellow academy students one day in the 1950s, ignited a film revolution — the Czech New Wave.

Guiding principles were drawn up, and the movies to come introduced Czechoslovak film to much of the world, while obliterating the country’s moribund “socialist realist” cinema. By the ’60s the slow thaw of de-Stalinization in Moscow had moderated the Czech government’s worst excesses, but a severe brand of communism survived.

“We were all united, one way or another, with desire to expose the regime on the screen,” says Ivan with pride. “And we got away with it because the regime was melting.”

Influenced by cinema verite and Italian neorealism — but most of all, by what Milos called “the stupidity of the films made at the time” — the New Wave movies depicted real Czechs in stories infused with the peculiar Czech brand of absurdist humor — while deftly ridiculing authority. In the Czech iteration, Milos had said, verite meant that “lies must be challenged.”

In 1968, the movement was ascendant: Jiri Menzel’s “Closely Watched Trains” won the Oscar for best foreign language film, the second Czech winner in three years.

Milos, at 36, was the New Wave’s leading light and already an international name. His “Loves of a Blonde” was as original a work as any from Truffaut or Antonioni, and funnier. It was a commercial and festival smash, and a 1967 Oscar nominee.

Ivan had a hand in all his friend’s Czech films, as co-writer, assistant director or both. It was Ivan who introduced him to Miroslav “Mirek” Ondricek, cinematographer on Milos’ 1963 debut, “Audition,” and most of the films throughout his career.

Ivan’s own debut feature, “Intimate Lighting” of 1965, was a warm and melancholic masterpiece of economy. It is today regarded among the greatest Czech films ever made.

Throughout the period, new films were routinely delayed, altered or suppressed by government censors. The Ministry of Light Industry initially objected to “Loves of a Blonde” because it portrayed a town of female factory laborers as something less than a workers’ paradise.

Then came “The Firemen’s Ball” in 1967. Co-written by the regular Forman team of Milos, Ivan and Jaroslav “Jarda” Papousek, it is a hilarious allegory on the corrupt bungling of Politburo groupthink. When President Antonin Novotny screened it, he reportedly “climbed the walls.”

In an absurdity faithful to the film’s theme, its fate was complicated by official conclusions that it was insulting to firefighters. Milos, Ivan and Jarda had to tour the country addressing fire brigades to assure them they meant no injury.

The film wasn’t permitted in Czech theaters until July 1968, the height of the period of liberalization called the Prague Spring. But three weeks later, it was shut down: Russian tanks had arrived in Prague. Within weeks, 137 Czech protesters had been killed and hundreds wounded.

::

On the night their country was invaded by allies, Ivan was in London and Milos in Paris planning films. Both men were married and separated; Ivan with a 9-year-old son, Milos with twin boys just turning 4.

Milos sent for his wife and the twins, but she longed for home, and they quickly returned. For Ivan, it would be 13 years before he managed to ferry out Ivan Jr.

When Ivan and Milos returned to Czechoslovakia that fall, the situation was tense.

The great filmmaker Milos Forman never spoke about his defection. In fact, he never called it a defection.

Czech leaders associated with Prague Spring had been arrested. Even “Intimate Lighting” was banned. Despite its benign subject, it committed the cardinal crime of ignoring the communists entirely.

Fearing their passports would be seized, Milos and Ivan furtively discussed getting out. “We didn’t have to talk too much about it. We knew we are going.”

On the night of Jan. 9, 1969, acting on a rumor, Ivan drove to a military barracks outside Prague, where he confirmed that a column of Soviet tanks was on the move. He hurried back to Prague and got on the phone. “Milos said, ‘Pick me up in an hour. We’ll go.’”

With their passports, a suitcase each and a few hundred dollars between them, they drove south in Milos’ car. What they lacked were exit visas, which were mandatory and difficult to obtain, especially for two who’d made “The Firemen’s Ball” and “Intimate Lighting.”

They were bound for Paris, where they had friends in the French film world.

It was 4 in the morning when they reached the Austrian border. There were patches of snow about, and the post looked deserted. An officer emerged from his shack, a Kalashnikov over his shoulder.

Ivan tells it:

“Comrades, where are you going?”

“We are going for a weekend to Vienna,” Ivan replies. The guard asks for their passports.

“Where are your exit visas?”

“They must be in the back,” says Ivan. As he gets out and begins searching the back for the nonexistent documents, he hears a dialogue from the front.

“Are you Milos Forman, the film director?”

“Yeeeees,” answers Milos in his deep voice.

“You know, I have seen all your movies.”

At this point in the storytelling, Ivan bursts with laughter. “And Milos, I swear to God, this is exactly what he said, and when I heard it I thought I might drop dead”:

“And I bet you didn’t like any of them!”

“Are you kidding?” says the officer. “You remember in ‘Loves of a Blonde,’ the ring and it’s rolling on the floor, under the table?” He proceeds to describe other favorite scenes from Milos’ films.

After more banter, the guard leans into the window and says, “Don’t look for the exit visas.” Waving his arm, he adds, “OK, gentlemen,” and opens the red-and-white crossing gate.

In parting, the guard says goodbye to the two travelers, but instead of the common phrase, he says, “Sbohem” — God be with you — which one Czech says to another whom he knows he’ll never see again.

::

A year later, government censors banned eight new movies and stopped production on 12. Nearly all the New Wave filmmakers who stayed were unable to make movies for years. Within a decade, Vaclav Havel was in prison.

For the two filmmakers in exile, their movies were forbidden, even eradicated from the literature — as if the work never existed — until Havel became president, after the Velvet Revolution of 1989. “The Firemen’s Ball” and three other New Wave films would be “banned forever.” Ivan was condemned to prison in absentia. Milos, presumably because of his celebrity, escaped a similar fate.

But a few weeks after Ivan and Milos fled, “The Firemen’s Ball” earned another distinction. It was nominated for an Academy Award.

::

“I thought the Russians are going to apologize to us and go back home,” Ivan says. He and Milos never thought they were leaving everything behind, “so it was easier for us to leave for a year than forever.”

Fifty years later, Ivan wears the badge of defection proudly, but Milos always downplayed it. In his autobiography, “Turnaround,” co-written with Novak, he makes no mention of his flight with Ivan. Milos worked for a while under a Czech Filmexport contract, so he was careful not to antagonize authorities back home — which paid dividends when they permitted him to return to Prague to film “Amadeus,” his greatest triumph.

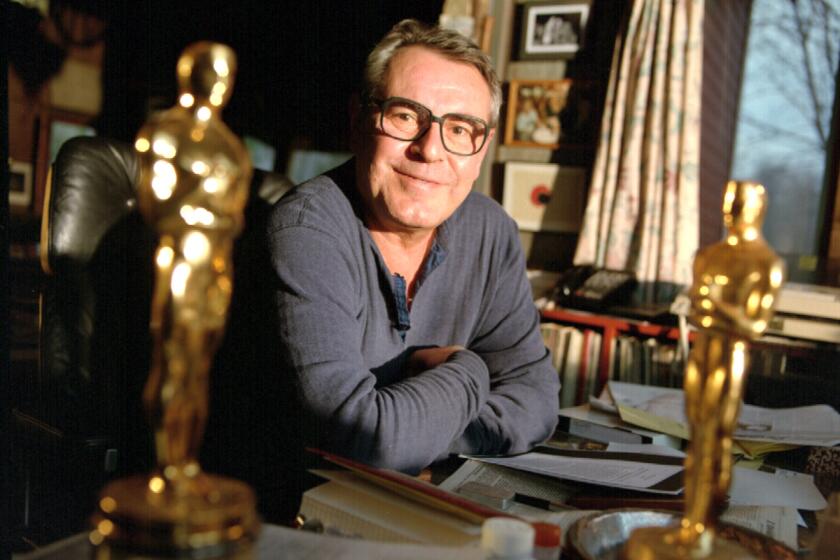

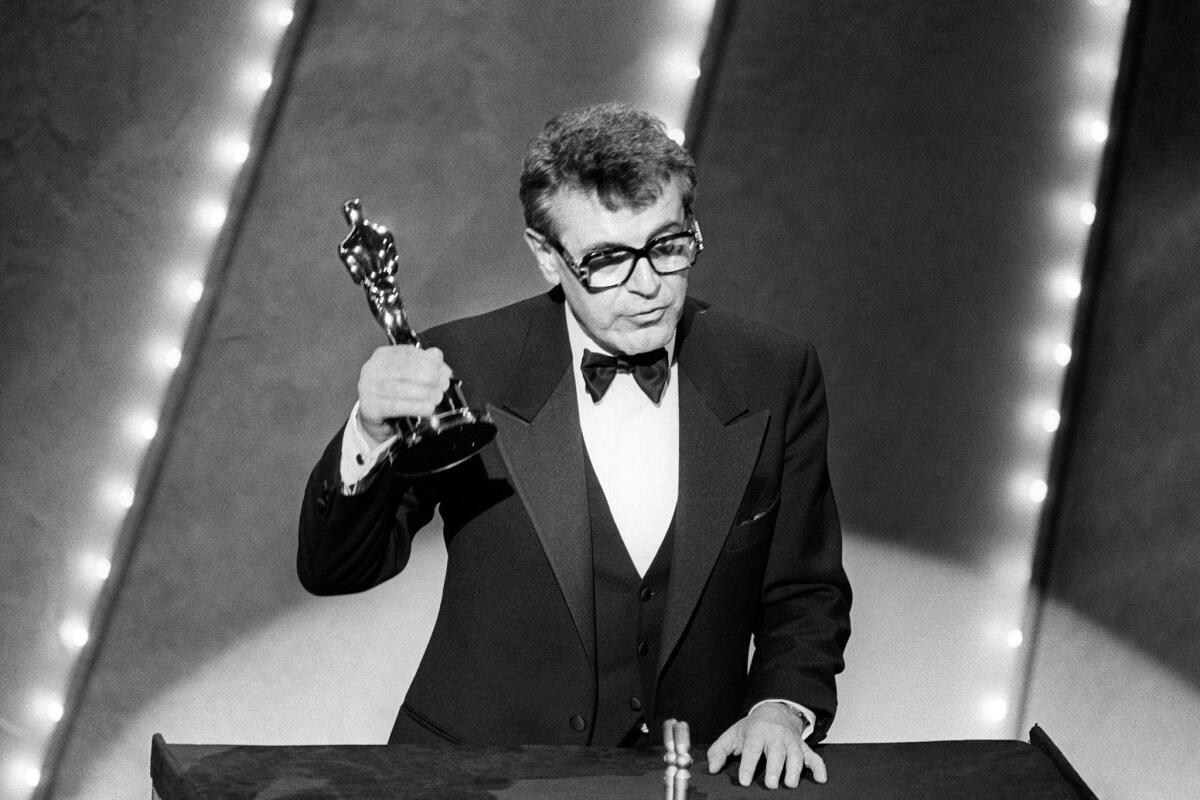

“Amadeus” won the best picture Oscar in 1985, as had “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” nine years earlier.

After Ivan moved to L.A. from New York in 1981, he and Milos visited often, and still they battled like schoolboys, in ping-pong and billiards, tennis and chess. “When the two got together, there was a lot of love between them,” said Novak.

They spoke regularly by phone, sometimes daily. “And to the end,” said Anne Passer, Ivan’s wife of nearly three decades, “they were still talking and chatting and discussing and trying to put the world right.”

::

“We got lucky,” says Ivan, who has three film projects in the works. “There is a saying: Make an effort, and universe will help. I found out that it’s very often true.”

In spring of last year, Milos and Ivan were both ailing, in hospitals on opposite coasts. Ivan emerged weeks later, marveling at a new bit of good fortune. During a procedure to treat an arrhythmia, a clot was discovered, mere inches from his heart.

Milos died near his home in Connecticut on April 13, 2018. He was 86. Tributes were held at Cannes and Karlovy Vary, the premier Czech film festival, and in Prague, where today one can visit Milos Forman Square.

Director Milos Forman was shaped by European sensibilities but his films were shrewd and intimate portraits of the yearnings, transgressions, politics, sexual fascinations, rebelliousness and complicated conformities that soothed, rattled and challenged the American spirit.

Back at Hugo’s, the conversation turns to losing his friend, and Ivan falls quiet. He starts to answer, then stops. A long silence. He tries again. But only sobs come.

The tears continue as he speaks finally, haltingly: “I realize now — how lucky I was — that I met him. How much richer life I have because of him. ...

“When he died, I realized, there is this — empty space inside of me. Which surprised me. A totally new experience. I never felt that, even when my parents died. ... Because I had this wild childhood. Mother was in the mountains, father was in a labor camp. So I was never terribly close to anybody. ...

“In a strange way, you know, I never accepted that he’s not here anymore. It was the first time I — experienced a full impact of that. It seemed to me, somebody dies, it’s like going to a train, and going away. But the finality of it, I was not too conscious of.

“I know very clearly I was very lucky.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.