Knocking on doors, climbing through fences: How L.A. County’s health investigators are out trying to stop syphilis

Roberto Rocha has been yelled at and called names. Men have threatened to shoot him. He’s visited jails, knocked on doors and approached strangers across L.A. County — all in search of syphilis. (August 30, 2017) (Sign up for our free video newslett

Roberto Rocha has been yelled at and called names. Men have threatened to shoot him. He’s visited jails, knocked on doors and approached strangers across L.A. County — all in search of syphilis.

The centuries-old disease referenced in Shakespeare plays is making a comeback, and Rocha is trying to stop it, one infected Angeleno at a time. Though its initial symptoms are mild, syphilis can lead to paralysis, blindness and miscarriages if left untreated.

Every day, Rocha and dozens of other L.A. County public health workers get in their cars to search for people who might have been exposed to

But the leads Rocha gets on partners can be vague at best: He hangs out at a doughnut shop in the afternoon. He lives somewhere in a three-story apartment building across from a liquor store.

Rocha once parked near a freeway bridge where he’d been told he would find a patient’s former partner, armed only with his nickname and a description of his tattoos. Rocha climbed through a hole in a chain-link fence.

“There were six people living under the bridge in a crevice, and I went in there asking for the person,” he said. “He happened to be laying there in the corner and I talked to him…. You see a little bit of everything with this job.”

For years, work such as Rocha’s has prevented infections and even saved lives. Even though their main focus is STDs, public health workers may refer patients to rehab, help them get out of abusive relationships or find them doctors for other ailments.

But with syphilis rates in the United States the highest they’ve been in decades, experts are taking a second look at what’s causing the new cases and also whether work like such as Rocha’s can actually halt the rapid spread of the disease.

‘They call you the worst of things’

Rocha, 42, wanted to work in public health when he graduated from UC Irvine in 2000. He started out in a lab but didn’t like being cooped up. He took a job with the L.A. County Department of Public Health the following year.

Rocha calls patients recently diagnosed with syphilis or

Many don’t want to talk to him. They shout.

Rocha leaves a letter with his contact information in their frontyards, or slips it under the doorway. He returns later. Rocha, who was recently promoted to a supervisor role, teaches his underlings this persistence.

“They slam doors on you, they yell at you, they call you the worst of things,” he said. “They’ll call you later on.”

When Rocha does hear from them, he has to quickly get personal. He needs to know the symptoms of the infection — where was the sore and when did the patient notice it — so he can determine if they transmitted it to anyone else. Then he asks them who else they’ve recently had sex with.

Syphilis rates are soaring

When Rocha started working at the department, syphilis seemed to be on its way out. Case numbers were so low that the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention launched a nationwide campaign in 1999 to eradicate the disease.

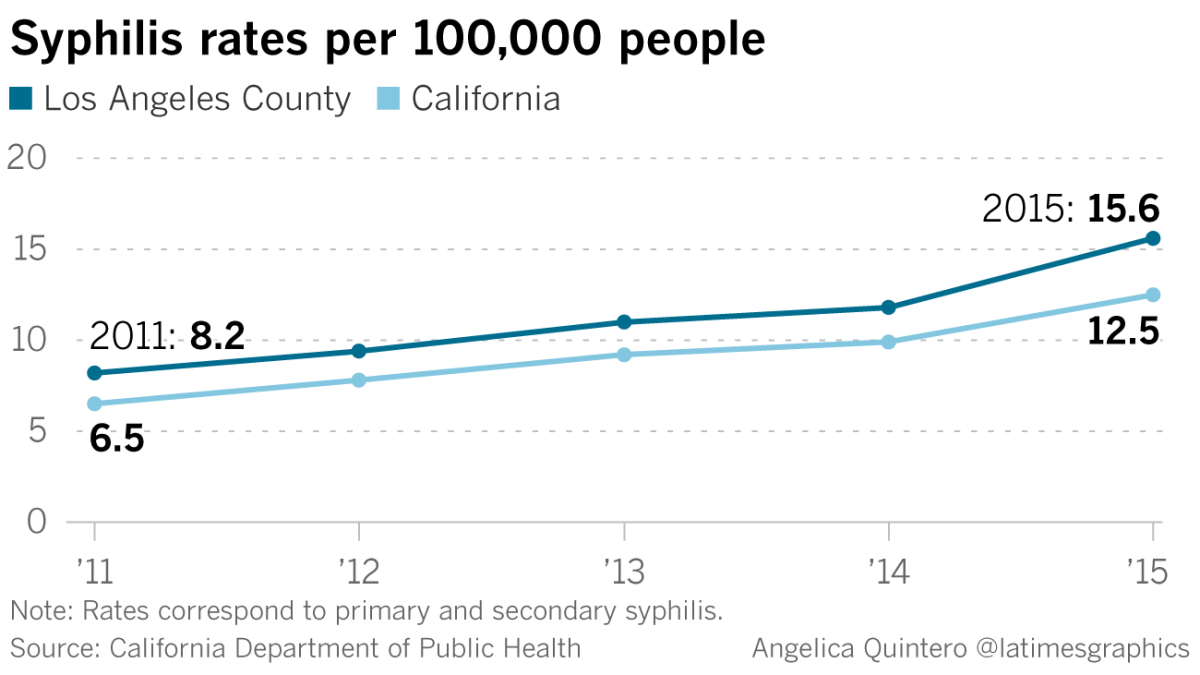

Yet syphilis rates have risen almost every year since the new millennium, picking up steam in the last few years. The number of infectious syphilis cases nationwide quadrupled in 15 years to 23,872 in 2015, according to data from the CDC.

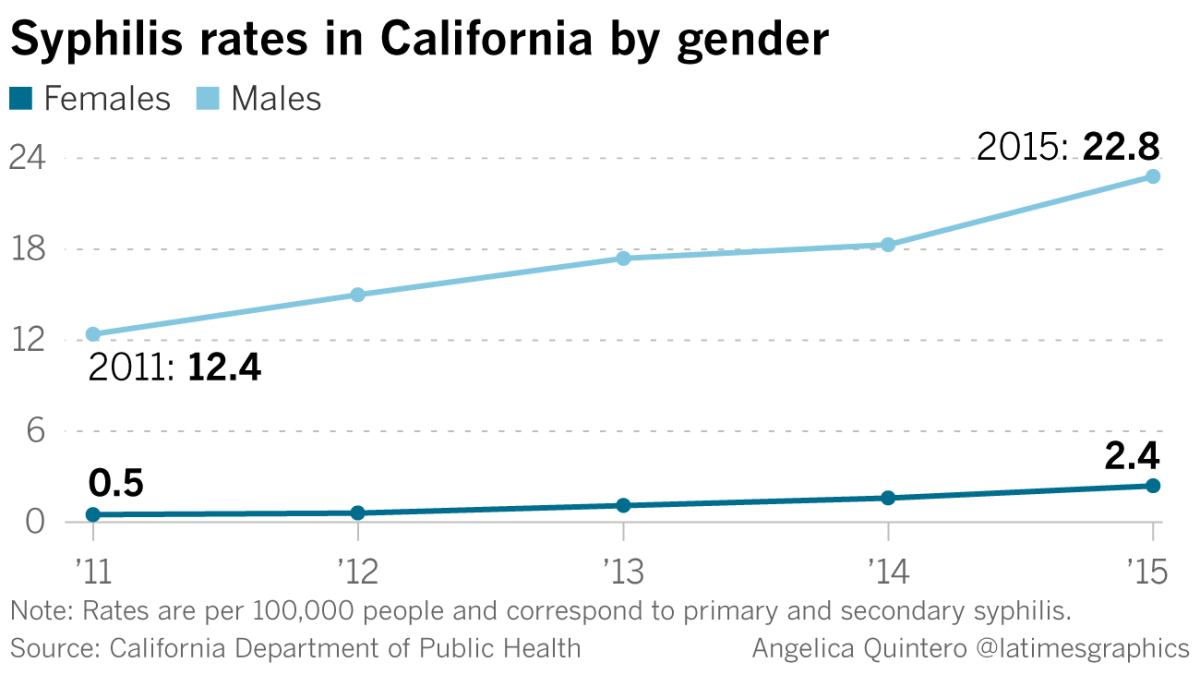

The majority of new infections for years have been in men, particularly gay and bisexual men. This summer, the L.A.-based AIDS Healthcare Foundation erected billboards in the city as well as in Oakland, Dallas and Chicago warning of a “Syphilis Tsunami.”

Doctors say people might not notice when they first contract syphilis, because the first symptom is a painless sore that goes away on its own. A rash might come later. Left untreated for years, syphilis can damage internal organs and spread to the brain.

Syphilis can be cured with a shot of penicillin, but it’s causing problems before it’s being caught. In recent years there’s been an uptick in California of ocular syphilis, a rare symptom of the disease that can cause blindness.

Syphilis can also spread from pregnant mothers to their babies and cause miscarriages, stillbirths and deafness.

In 2015, 142 babies in California were born with congenital syphilis, including 23 in L.A. County. Just three years earlier, there were only 33 babies with congenital syphilis in California and seven in the county.

“I think what’s alarming is that there’s been such a jump,” said Amy Moy of the California-based advocacy group Essential Access Health.

Many blame the rise on underfunding for STD prevention programs. In 2012, more than half of state and local STD programs faced budget cuts, leading to fewer clinic hours and resources, according to the CDC.

Public health officials also say that gay men are using condoms less as fear of HIV has fallen. Some also speculate that hook-up apps have led to people having sex with more people because it’s easier to find new partners.

“It’s all of those things coming together and creating this perfect storm,” Moy said.

Can anything be done?

Years ago, Rocha visited a 14-year-old girl who’d been diagnosed with syphilis. She had run away from home and was dating a 25-year-old man.

Rocha also learned that she was addicted to methamphetamine and that her boyfriend was supplying her. He had tattooed his name on her. Rocha reported the man, who ended up in prison.

When he meets with a patient, Rocha doesn’t just ask about sexual habits.

He inquires about housing and mental health. He might even set up transportation to a drug rehab center. If he’s talking to a patient who’s in jail, he’ll ask how they’re being treated and whether they have access to their medications.

He wants to get at the root of what’s causing them to engage in high-risk behaviors, he said.

“We’re trying to help them in different ways,” he said. “We want to make sure they’re OK.”

Another time, Rocha showed up at the home of an 18-year-old who’d just been diagnosed with HIV but hadn’t come out to his parents as gay. He asked Rocha to sit with him while he revealed both pieces of news.

Dr. Sonali Kulkarni, medical director for L.A. County’s division of HIV and STD programs, said the work of these disease intervention specialists — there are about two dozen in the county — can have a tremendous effect on people’s lives.

But amid the growth in syphilis cases, health officials are reevaluating this one-on-one approach to STD prevention. It gets patients into treatment, but there’s little evidence that it reduces transmission and syphilis rates overall in the community, she said.

Part of the problem is that people won’t name their partners.

Rocha recalled one man who emailed an investigator a list of 100 names and phone numbers of people he’d slept with in the past year. But more often they’re hesitant or don’t know the names of people they’ve had sex with at bathhouses or met online.

“We’re happy if we just get one person,” Rocha said.

Kulkarni said they’re thinking about other ways to tackle the disease. Concentrating on patients with HIV is important, because more than half of new syphilis cases are in people who have HIV.

She also said they might focus their outreach on certain neighborhoods where lots of people have been infected. Additionally, there’s early evidence showing that syphilis patients aren’t connected to each other through a sexual network, but through drug use, she said.

“There’s more room to better understand what we could do to decrease the spread of syphilis,” she said.

For Rocha, his work has become about much more than STD prevention.

He recalled visiting the home of a 19-year-old who’d recently been diagnosed with syphilis and HIV. The boy’s grandmother opened the door.

“She let me into his room. He was skin and bones…. He had stopped eating, stopped doing anything,” he said. “He thought his world was over.”

The patient thought HIV was a death sentence. Rocha explained to him that people diagnosed decades ago are living happily today, he said. He told him he could get assistance to pay for the medicines.

Rocha headed out of the home and was approached by the boy’s grandmother, who was crying. She thanked him.

To read the article in Spanish click here

soumya.karlamangla@latimes.com

Twitter: @skarlamangla

ALSO

She watched her ex-husband end his life under California's new right-to-die law. 'I felt proud'

An LAPD officer needs a bone marrow transplant. His ethnicity limits his chances of getting one

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.