- Share via

This story is part of Image issue 7, “Survival,” a collective vision for the L.A. of our dreams. See the full package here.

Hi Gorgeous,

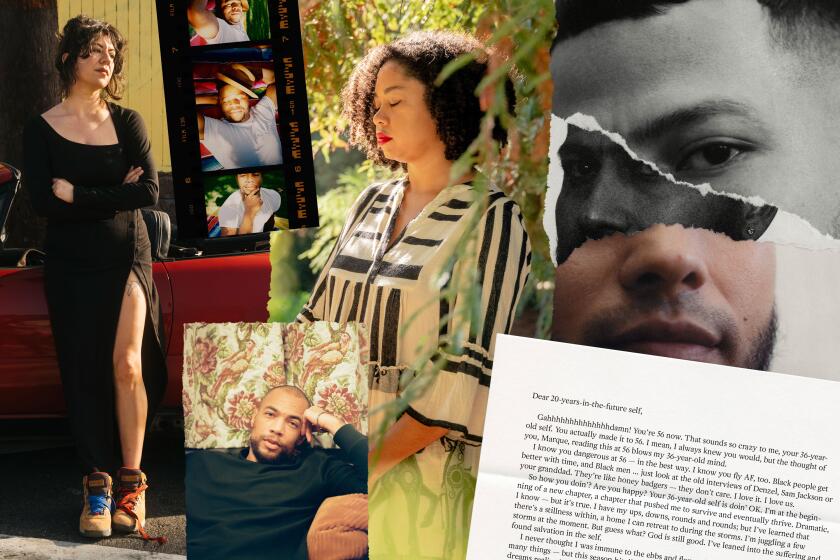

When Eleanor was stolen, I spent our 24 hours apart hobbling between grief and release. When you and I were together, you wanted me to have whatever I wanted, and you had the money to deliver on my desire. I took the tennis racket, the necklace, countless Postmates dinners, white takeout boxes blooming open on your dining room table like sauce-stained carnations while I worked on deadlines; I took the plane tickets to Venice and, finally, this car, named after America’s sexiest first lady, you like to say. I accepted these things but I could not see them for what they were, what they actually meant. Penance. Trinkets meant to substitute the one thing you couldn’t give: yourself.

On our first date, you zipped me around in your little white Miata. I told you that a Miata had been my dream car since I was a teenager, and you laughed because dream cars are supposed to be expensive, or at least rare, and the Mazda Miata, a Japanese car company’s chintzy version of a British roadster for the American market, is neither of those things. I saw a meme once that said Miatas are for short, angry men who can’t afford Porsches for their midlife crises. One commenter on the Kelley Blue Book webpage refers to his Miata as “a reliable little pony, born in 1993,” and I have noticed something Humbert Humbert-esque about the language men use to wax poetic about their Miatas. You were none of those things.

When you and I broke up, I thought about pushing her off a cliff. I’d done it once before, with a friend’s car, in high school. Took the license plates off and scratched the VIN. If some civic authority ever caught up to her about it, I wouldn’t know because I haven’t talked to her since. You and I were not on good terms at the time, but when Eleanor was stolen, you reached out to me. I called you back. The nature of our intimacy at that moment was odd. Everything bad between us briefly evaporated. We talked about the car like divorced parents whose child had been kidnapped, even as I was ashamed to admit such was the depth and character of my sadness. I was always a bit shy about posting photos of you on the grid, but my love for Eleanor was always Instagram-ready. As word of her disappearance spread, a stranger DM’d me to say, “You seemed to have a very special connection with that car, like it was a part of you.” It made me angry. I was spiraling about what it all meant, intellectualizing my grief into metaphor. This is a good thing, I told myself, it’s a symbol of moving forward with my life. It wasn’t until the police called me to say they found her that I burst into tears. That jerk on Instagram was right. I just really liked the car. I always kept a spare baseball cap in the glove box for my passenger. The first time you and I fought after getting Eleanor, I sped off to my parents’ house, going 70 mph with the top down on the 60 west, crying and then laughing because crying in a convertible is so much fun it makes you stop crying.

These letters are part of Image issue 7, “Survival,” a collective vision for the L.A. of our dreams.

“The Miata,” Arthur St. Antoine wrote in Car and Driver magazine in 1989, “delivers an overload of the kind of pure, unadulterated sports car pleasure that became all but extinct 20 years ago.”

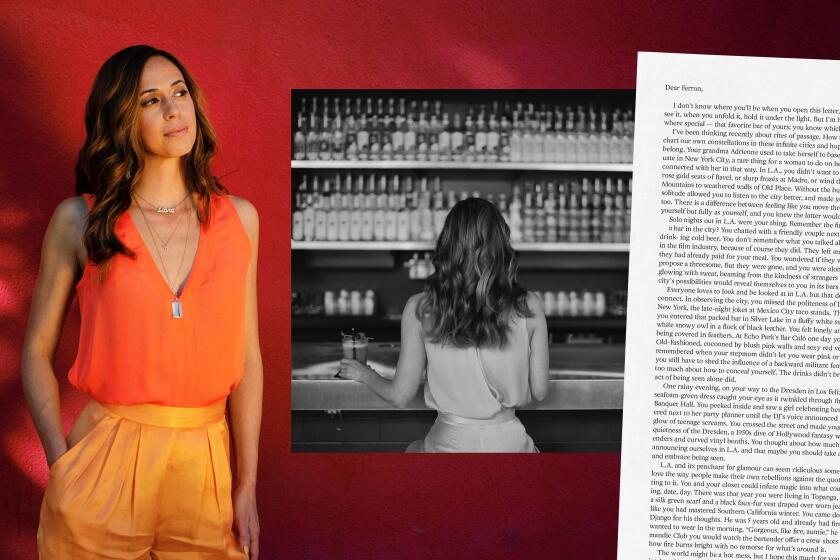

It’s hard to explain. L.A. is a car city, and this is a peculiar source of anguish for the broke. Before Eleanor, I’d never had a car that was a pleasure in itself to drive. I scraped together what I could and bought whatever was the cheapest thing being offloaded by a friend or acquaintance finally ready to leave L.A. for good. The greater part of my driving life has been characterized less by “unadulterated sports car pleasure” and more by unadulterated fear that this thing will break down, or get towed, or any number of nickel-and-dime-ish indignities that constitute the Kafkaesque cold war between myself and the Los Angeles Parking Violations Bureau. There had been, throughout my 20s and early 30s, a general upward trend in vehicle reliability. I know I’m doing better because I see Jimmy less and less. I’ve been going to Jimmy at Pacific Auto in Silver Lake for 15 years. Every time I’d roll into his shop with some new beater, slightly less old than the one before it, he’d smile and say, “Upgrade!” And every time I came in with a new boyfriend, he’d smile and say, more slowly and low enough for only me to hear: “Upgrade.”

Inside Issue 7: Survival

Writer Rembert Browne investigates the mysterious ailments that just showed up one day

Writer Zinzi Clemmons wants you to be able to stay in the city as long as you want

Artist Muna Malik recycles the emblem of a failed democracy

Journalist Cerise Castle pays tribute to the city’s forgotten site of refuge and devastation

Actor Marque Richardson lets us in on the only 20-year-plan that matters

Eleanor was so reliable I made it a point to visit Jimmy in between oil changes, just because. In one sense it’s the longest relationship I’ve ever had. This year, she started to break. Eleanor was born in 1997. She runs as well as ever but not clean enough to pass smog. I started seeing Jimmy almost every week as he changed one sensor or hose or other and wouldn’t even charge me if the check engine light turned back on, which it always did. Her tags were nearly a year overdue, and I was getting tickets again. I felt like she was turning on me. I know my humble dream car won’t last, and her demise, unlike her theft, is symbolic.

I feel like the markers of upward mobility I’d latched onto in my youth are slipping through my fingers, and the waning feasibility of keeping Eleanor smogged is a portentous synecdoche of a larger order failing in such a grand and fundamental way it can only bubble up in the particulars. When her last sensor was replaced and I left the smog-check-only center clutching my pink smog certificate, I called Jimmy, like a proud daughter, to tell him the good news. “Well,” he said, “that buys you a couple more years.”

Tennis soon,

Christina

Christina Catherine Martinez is a writer, actress, comedian and daughter of Los Angeles. She is a recipient of the Creative Capital/Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant and has been named a Comedian You Should Know by both TimeOut L.A. and New York Magazine. Her book of essays, “Aesthetical Relations,” is available from Hesse Press. She was born and raised in Southern California.