- Share via

This story is part of Image issue 10, “Clarity,” a living document of how L.A. radiates in its own way. Read the full issue here.

In the world of lowriding, a car club plaque serves as a sacred language.

The name of your club, usually cast in bronze, flying in the front or back of your ’75 Cadillac or ’64 Impala is shorthand for your morals, values, aesthetic taste, work ethic, willingness to sacrifice. To the casual onlooker, a lowrider plaque is merely another shiny accessory on an already mind-blowing piece of machinery — an appreciated extra, like the gold nameplate all your cousins wore in the ’90s. But for those in the culture, it’s everything. There are guidelines, varying from club to club, one must adhere to not only to get a plaque, but keep it. These codes of conduct extend beyond what shape your car is in (though that’s a crucial part of it) to your character. Reason being: When you fly a plaque, you’re flexing your family — it’s not just about you anymore. Plaques are a way to show respect and gain it, simultaneously.

More stories from Clarity

Maggi Simpkins shows what it takes to cut it as a jewelry designer in the Diamond District.

Anwar Carrots outlines the future of streetwear collabs.

Julissa James gets to the bottom of what an L.A. night really smells like.

Dave Schilling searches for the holy grail of L.A. outerwear.

Georgina Treviño reveals that everything has a little jewelry language in it.

The making of a lowrider plaque is an art form in itself. Clubs carefully select fonts, designs and sizes to stand out from the others. Plaque makers turn this vision into something tangible through a finely honed craft. “You’re customizing it to reflect how you view yourself in the world,” says Denise Sandoval, a professor of Chicano/a studies at Cal State Northridge specializing in lowrider culture and Chicano cultural histories.

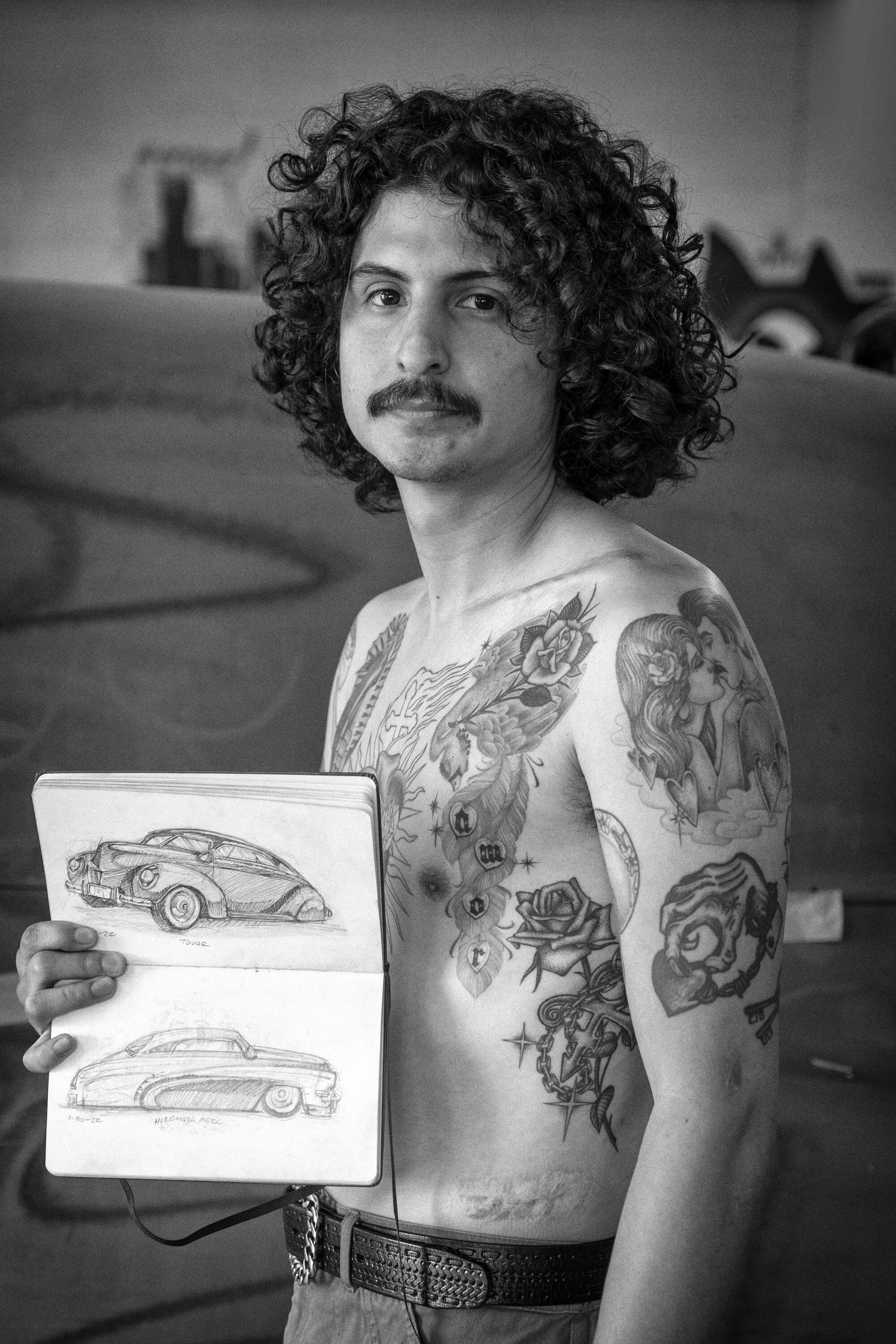

For this feature, we talked to the true aficionados of the culture — club members, artists, plaque makers, photographers and scholars — about the meaning behind car club plaques and what it feels like when they hit the light just right. And for good measure, we tapped lowrider stalwart, tattoo artist and designer Jesse Jaramillo to make an original plaque for their new club, Prophets, which was then crafted by David Lopez of Bedsled Kustoms. “The nature of the work that I do with my tattooing, my design, is giving respect to the foundation that was laid before,” Jaramillo says. “I want that same thing to be applied to my lowriding. I would also love [Prophets] to be the dawn of a new age of what a lowrider club can look like, who’s invited — all the girls, gays and theys, all of us.”

Jesse Jaramillo, tattoo artist, designer, founding member of Prophets car club: For my family, our car was the first outward expression of the culture that we represent. Like, these are the things we live in. You’d unashamedly drive it around town and just flaunt that.

Like a lot of things in Chicano culture, [plaques] followed this idea of pride. It connected you to your community. It was one of those things that, depending on which one you saw, you knew what those people were about. You knew how they built their cars, and you just knew they did the damn thing to have that plaque.

Alejandro Perez, half of the Perez Bros., fine artists who depict lowrider culture in their work: I feel like a lowrider plaque definitely carries a big sense of pride, but also it’s a form of validation. Every car club has their own standards for a lowrider to be able to join. One puts many hours of hard work and effort to get their lowrider looking beautiful and just right. Once their lowrider is complete, and they are able to join a club and get their plaque, it is validation that all the hard work paid off.

Paisaboys is a brand built on innuendo. Its ethos might best be described as a hint — a highly specific yet deeply relatable nod toward The Culture.

Denise Sandoval, professor of Chicano/a studies at Cal State Northridge, curator and scholar on lowrider culture and Chicano cultural histories: People don’t realize that when you join a club, you’re not just automatically given a plaque. Most car clubs have infrastructure — a president, vice president, sergeant of arms, secretary. They are the ones that determine if your car is ready to have the plaque. The car obviously is the owner’s canvas of creative expression, of their identity, their beauty that they want to put out in the world. But then when you’re in a club, your car is representing your car club as well. Not just yourself, but your car club. Whether it be from an aesthetic standpoint, whether it be from the reputation of the car club.

David Lopez, plaque maker at Bedsled Kustoms, founder of Relics car club: The plaque is sacred. It’s something sacred to these clubs and they earned them. To get a plaque, clubs set their standards up. Whether it’s time with the club, whether it’s building the car, whether it’s how much effort you put into helping others, it’s an earned piece. And it’s really cool to be a part of that. I’ve helped new clubs get their name started. One of the clubs that came in, I gave them their plaques and they said, “Man, it’s almost like getting baptized.”

Estevan Oriol, photographer, director, founding member of Pegasus car club: I’m with a club called Pegasus — this year is our 10-year anniversary. I was with a car club for 20 years before that called Lifestyle. [Around 20 members broke off from Lifestyle to form a new club with Pegasus.] We made a vow to never be from another club, so we did the nomad, outlaw crew thing with people from the same club, but we never again put up another plaque on our car out of respect to our forefathers. They call it club hopping when you go from club to club to club. Plaques are like putting your family name on a lowrider.

What I had to go through to get a plaque with [Lifestyle] was to get the three highest guys to approve my car. Everybody had seen my car for months, and I had been hanging around, staying out late, going to the guys’ houses to help work on some of their cars. They saw the car and were like, OK, that part is cool, now let’s get to know this guy, because each person is carrying around the club on their shoulders. You don’t want a guy who gets drunk at a party and starts talking s— and then says the car club name and then gets beat up. You want people that know how to handle themselves and know how to act.

David Lopez: Once they get their logo figured out, I like to tell them, All right, so how big you want to go? You kind of base it on the size of the cars and the windows, you also want it to be legible. You want to be able to read it and see that shape and know that name. You’re giving everybody their own personal stamp, you know?

Once you get the logo, you transfer that into the wood and you carve out the pattern — basically cutting wood like you’re making a puzzle. The pattern goes into a sandbox and that leaves the impression in the sand (the sand is packed really tight, by the way). That’s when the metal is heated up and poured into the mold, kind of like candle wax. When it comes out, it comes out raw and then it gets all the drills and files and sanders. After all that, you go and polish up the piece.

Artists Nikko Hurtado, Arlene Salinas and Steve Butcher take you inside one of the most intimate energy exchanges in the world: tattoo portraiture

Mark Hocutt, custom car painter, president and founding member of Prophets car club: Most plaques are generally made of brass, and brass stains very, very easily. If there’s a stain on your plaque, it’s like spitting in your grandma’s face. It’s one of the worst things you can do. When I was in my previous club, I used to clean my plaque every time I went out. It takes an hour, hour and a half to clean it. And then it’s the dedication, the dedication that you have for your club. You want to represent the best way that you can.

David Lopez: When I make a plaque, it’s like putting future relics into the world. It’s a piece that somebody’s going to collect or somebody’s going to cherish and somebody’s going to have on their wall. Sometimes plaques have even been buried with members of their clubs. They’re really special, and to be a part of that, it’s always an honor.

Estevan Oriol: When you put the plaque up on your car you’re like, “F—, man.” You feel like you made it. Another milestone, another achievement in your life. A car club that has reputation, history and culture — you know, there’s a lot of blood, sweat and tears invested into that plaque.

Jacqueline Valenzuela, fine artist, hand-painted custom car muralist, founding member of Prophets: It’s a big deal to have one in my car. I’m proving to myself that my car was good enough to get a plaque in it, or that I was taken seriously. Depending on what kind of club it is, you kind of know what type of person has that plaque. They’re like telltale signs.

Denise Sandoval: When you see the plaque, there’s greater politics at play that people are unaware of. When you think about the oldest Chicano car clubs in L.A. — the Duke’s, the Imperials, some of the longest-lasting African American clubs, like the Individuals, the Professionals — these names represent a regalness and an elegance. These names are elevating us, they’re our way of setting a standard. In this sense, we might be working-class, we might be poor (and I’m talking about the ’60s and the ’70s), but there was a sense of royalty, like these cars are our chariot.

Vicente Perez, half of the Perez Bros., fine artists who depict lowrider culture in their work: One of my earliest memories was seeing my dad’s plaque in his car. Super Naturals was the name of the car club. For some reason I really liked the design of it, and I was surprised to find out that there were many more car clubs with different names out there. Each car club had its unique name and plaque design.

Denise Sandoval: The plaque, in representing the club, also marked out space. These car clubs would have their meetings in certain spaces. It’s all tied to the landscape of the barrio. Car culture and car club culture really emerged post-World War II. There was just this fascination with cars as an expression of your individuality. Every club would have the place that they would set up when they would cruise Whittier Boulevard in the ’70s.

Estevan Oriol: The other thing with the plaques is that if something happened to your car — like you got a flat tire — the first thing you do is take your plaque down. That was automatic. If you pulled over on the side of the freeway, take the plaque down. Because it’s not show quality. If you can’t pull it into a show the way it’s driving right then and there, you don’t need to have the plaque up.

Jacqueline Valenzuela: There was a club that [me and Mark] were a part of from the beginning. It was fun at first, but it became more and more apparent that I, in particular, wasn’t being taken seriously. It was a domino effect, little things that were happening — like it was a joke that I was the secretary for the club. Plus, I never got an actual plaque. There were endless excuses. It was obvious that the reason for me not getting a plaque wasn’t my car. It was because I was a woman.

Once it was made clear that I wasn’t going to actually be in the club, that’s when we were like: Well, you know what? Maybe we need to be around people who are closer in age to us, who have similar views to what we have, because that makes everything so much easier.

Follow Fairfax O.G. Anwar Carrots and you’ll realize it’s not about making stuff; it’s about making stuff look cool.

Mark Hocutt: With Prophets, we’re focusing on the character of the person. We want really good people around in the club and everything, but their cars also have to speak for them. Obviously, everybody’s going to look at their car and the plaque in the back and see “Prophets.” So now, you’re not only yourself, you’re a member of this club.

Jacqueline Valenzuela: I hope our plaque would communicate that we did the damn thing. It’s really hard to start a club. It’s a lot of background work. I know for us, all of the work that we do — even in our personal artwork — it’s very community-based. And it’s something that we want to share with our community. The club is an extension of that. We want to do fundraisers for the community, we want to make things accessible for our community. To me, it’s cooler for you to think of that when you see our plaque than for you to think, Oh, they have cool car shows. But obviously, we also want our cars to be top-notch.

Mark Hocutt: When you think of L.A. and you think of things that shine, one of the first things that you think of is the lowrider. The shine is the cherry on top. There’s nothing like the composition of colors, then it looks like there’s a big piece of glass all over it. Like, the car is the frame but it’s also the picture. Then, you know, you look for that plaque: This is a badass car. What is it?

Denise Sandoval: When you think about shine, it becomes so important how we’re using culture to build community and to really put something out in the world. You would think these plaques and this shine is just for the lowrider, but they’re also bringing a brightness to our communities.

I think what custom [lowrider] culture brought was this idea of creating a unique sense of what it means to be American through your car, through an American-made product. You’re customizing it to to reflect how you view yourself in the world.

A brother [from the Duke’s car club] told me that a true lowrider rides from the heart, and there’s a difference between a true lowrider and a lowrider wannabe — those people that were not living up to the plaque and to the codes of the street.

More stories from Image