- Share via

In the beginning, I imagined my escape as a temporary interlude. I was a young writer, and not unlike most young writers, I wanted to author my dreams. I was eager to give them the shape and heat of purpose. I wanted to live in and through them, not merely fantasize about the possibility of what awaited me. So after 24 years, and with no intention of swift return, I left Los Angeles and everything I knew.

I arrived in New York City on July 4, a Sunday, and somewhere beyond the edge of yesterday, in the melody of my exodus, questions lingered. How exactly would I carry home with me? With this new language I sought, could I write a different story while holding on to the one I was already in? Would I have to discard the old story for an entirely new one — or could I fuse them into something miraculous and true?

The first attempts at this were a passive exercise in mental upkeep. I relied on personal ornaments to keep the embers of L.A. fresh and alive. During my final two years of high school, at Culver City, I carried a disposable 35mm Kodak camera everywhere I went. I wanted to capture us as we were: blissful and unguarded, worthy of commemoration. I logged our last moments together with a diligent, unblinking eye, and by graduation I had amassed hundreds of photographs.

Haley Mlotek and Thora Siemsen exchange emails about leaving New York: ‘The version of New York I miss most is the one I see in the movies and probably never actually quite experienced, and otherwise I just miss people.’

Amid my earliest days in New York City, plagued by homesickness, this was how I remedied my acute longing for everything I left behind. Rather than romanticize what I missed, I furnished my memory with a visual collage. On nights I felt alone, or wanted to bridge the distance between me and everyone I loved, or craved the cushion of nostalgia, I sifted through my collection.

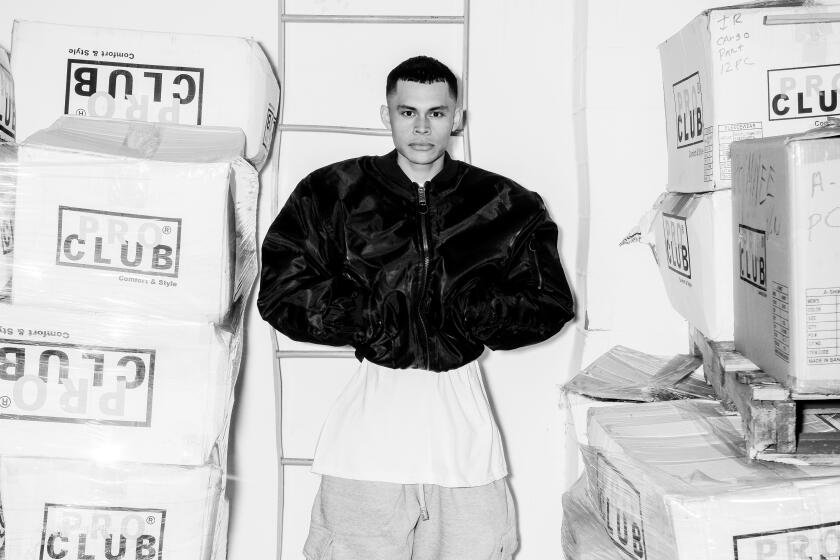

And there we were: Ashton and Kareem posing in their Pro Clubs; Diana, Alex and Angelica styling their faces into funny shapes during third-period trigonometry class; Claudia and me on the lunch yard, with me doing my best Jay-Z cosplay in a gray Rocawear long-sleeve T-shirt and the words “HOLLA BACK” written in white-out pen on my JanSport backpack. During those early months in New York, I committed to memory jeweled moments with family members, like in the photograph of my cousin, Breann, standing between my brother and me during my aunt’s wedding reception in San Pedro in 2007. What I saw was what I felt. And what I felt was what I knew: Away from home, I could find shelter in these photographs.

Author and educator bell hooks once remarked that she felt “most real” in the realm of snapshots. I have a much more tenuous relationship to photography. I have always felt most comfortable outside the frame, as a witness, beyond its whir and click. I was an awkward, sometimes moody teenager and rarely felt at ease in my skin. Behind the camera I wasn’t simply out of view, I maintained control.

My absence from many of my photographs was, in part, by design. But I also knew that I couldn’t linger outside the snapshot forever. That maybe life was more worthwhile, was “most real” in the snapshot. This is what propelled me forward, first to college, and then New York City. I wanted to envision a new story. I wanted to take up space in the frame.

In December 1977, at the Modern Language Association Convention in Chicago, poet and activist Audre Lorde put forward a series of questions in a speech titled “The Transformation of Silence Into Language and Action.” (The address was later published in her 1980 memoir, “The Cancer Journals.”) “What are the words you do not yet have?” Lorde asked. “What do you need to say?”

The way we pay tribute to the iconic tee shows up in multitudes, governed by personal ritual. Inside the warehouse, Jess Cuevas and Pablo Simental show the level of respect needed to properly honor a garment so singular.

In New York, the frame alone would not suffice. I needed a story — the words I did not yet have but needed to say — to fit within it. All leavings summon something within us, and this was mine: the will to create an identity entirely of my own.

Lorde believed the very practice of speaking hard, personal truths; of facing the thing that for so long had numbed one’s power, and thus one’s freedom was an act of self-revelation — but was it self-revelation I sought in my leaving or simply distance from the person I no longer desired to be?

“I have come to believe over and over again that what is most important to me must be spoken, made verbal and shared, even at the risk of having it bruised or misunderstood,” Lorde continued. “That the speaking profits me, beyond any other effect.”

Not long after I arrived in July 2010, I started a blog. I titled it “Writing New York” and used it as a private online journal in the tenor of autofiction. Until I found my own story, I told myself, I’d write myself into one, stitching the truth of my days with the fiber of make-believe. I was slowly finding the words.

In time, however, I realized my leaving was not a story I could imagine solely online. Like Lorde, at the risk of being bruised or misunderstood, I would have to live it bravely. The beginning months were green and unpeeled. There was no narrator to guide me or caution my steps. The city was like a drug, with its euphoric highs and devastating depths. One does not neatly survive New York, the most successful transplants learn to tame it on their terms. Eventually I did.

Remarkably, my rituals for survival were all homegrown. I no longer lived in Los Angeles, but to make it in Manhattan, a labyrinth of opportunity and chaos, I would have to bring the best of what I loved about home with me.

Upon the altar of my memory, what tools should I place?

The appearance of survival varied by circumstance. During summer concerts in Central Park or afternoon walks through Fort Greene, I shielded myself in a Dodger fitted. Fanged by nostalgia, I scoured the five boroughs for foods I was raised on. I hunted for turkey tacos like the ones my mom made and became obsessed with finding churros that gave me the same sugar-crunch of adrenaline I got hooked on in my youth. I searched for sandwiches that rivaled the erotic sensation of biting into a Fatburger. I was rarely successful, but the pursuit of home meant it was always within reach. It meant that L.A. was always in view even if an entire country stretched between us.

I envy Knicks fans. I look over the white picket fence that separates us, me in my lavish, marble-appointed castle and them, with their quaint Craftsman that could maybe use a fresh coat of paint and some landscaping.

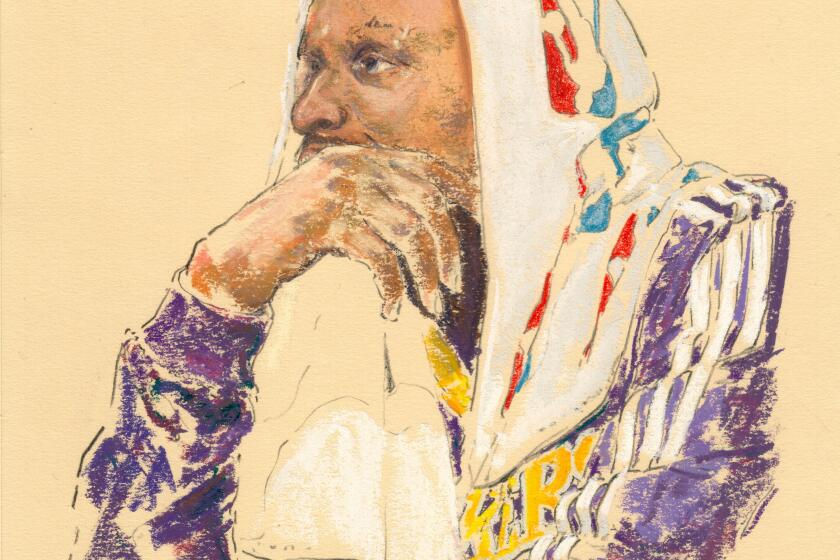

To survive required I fully give into my sensorial aches, so I watched and replayed regional classics: “Menace II Society,” “Love & Basketball,” “Next Friday,” sustained by the sounds and visual incantations of home. During late nights from October to June, as the clamor of Fulton Street ebbed to a hiss just outside my window, I watched the Lakers chase their former glory — quickly remember and then quickly forget the Byron Scott-Luke Walton dark age — wrapped in the glow of my TV screen.

In the spring of 2013, when Jim Gavin published his story collection “Middle Men,” a wry portrait of California dreamers who clumsily steer their way through the hopes and hazards of human existence, I read it in terrific haste, buoyed by his poetic appreciation for Del Taco. I held the same one. Later, on a whim during a work trip to Detroit in 2017, I got a tattoo of L.A.’s official city flower — a bird of paradise — across my right forearm, my personal reminder that I belonged to “a glorious flock … [from] somewhere special.”

In time, I learned. I was not in search of reinvention or rebellion. What I sought in the story of this new frame was a rejection of stasis. What I went looking for in New York was the person I always dreamed of being in Los Angeles. What I learned was that I needed space and distance to grow. And as I bloomed in New York, I was pushed to summon the memory of L.A. and all that I loved, and remembered, about it. To remember home was to become someone new. It’s true that memories are a comfort, but they also armor us, they help ready us, for who we want to be away from home. Memory is our most intimate relationship. It is a daily endeavor of excavation, a prayer of the mind. Memory is the ultimate commitment to unforget.

What I am now certain of is this: A person can also find home by leaving it. Because to remember what made you is to survive. And to survive is to honor everything that has made you.

Jason Parham is a senior writer at Wired and a regular contributor to Image.