A queer bar. A bedroom. A freeway. A swap meet. A billboard. “At the Edge of the Sun” celebrates the places, connections and references that make up a scene of artists and friends in L.A. The self-organized group exhibition showing at Jeffrey Deitch is about the choices, as Maria Maea says, that these artists have kept making in order to be in community with one another.

Over the course of the last decade — some relationships spanning even longer — Diana Yesenia Alvarado, Michael Alvarez, Mario Ayala, Karla Ekaterine Canseco, rafa esparza, Alfonso Gonzalez Jr., Ozzie Juarez, Maea, Jaime Muñoz, Guadalupe Rosales, Gabriela Ruiz and Shizu Saldamando have been in an evolving dialogue about what it looks like, and what it means, to make work in L.A. right now.

Being in the same room with these artists, a comfort and familiarity rises to the surface. Their own little world forms around them, where they all speak the same language and have been for a long time. These artists are peers. Their individual practices inspire and sharpen each other’s in subtle and overt ways. But they’re also homies. Their work is chock full of messages that are coded in an IYKYK experience. “It’s almost like a hidden highway system of information that we’re all tapping into unconsciously,” says Muñoz.

They knew that if “At the Edge of the Sun,’’ running from Feb. 24 to May 4, was going to come from them, it had to come from them. Organizing it themselves was a conscious choice — a rejection of outside forces grouping them together based on perceived identity and a belief that just because they’re artists working and living in L.A. at the same time, that they’re completely synonymous. (As Rosales says, “This isn’t ‘The Real World.’”) Instead, they saw “At the Edge of the Sun” as an opportunity to be intentional about creating their own narrative. “It feels pretty major for us to just take up this space,” says esparza.

The result feels like laying the ground for a new framework of what a show like this can do, and what it can be, for generations beyond. A way to create ripples that can outlast the moment where being a brown L.A. artist feels like it’s on trend. “They are defining art, creating it for themselves,” says gallerist Jeffrey Deitch. “They’re not fighting to be recognized. They’re articulating the new L.A. aesthetics. That’s the big difference.”

There are spaces in L.A. where congregation feels essential. A theme of the show is this idea of landmarks that are shared, personal and familial: studio spaces, backyard shows. Or the New Jalisco Bar, a beloved queer haunt in an old corner of DTLA that many of the artists — including esparza, Canseco, Ruiz, Rosales, Maea, Saldamando and others — have made a part of their individual histories and relationships with each other. (Ruiz and esparza painted the mural that meets you at New Jalisco’s entrance, and respectively helped organize and support a fundraiser that kept its doors open during the pandemic.) “When I think of my relationship specifically with Maria, Gabby, rafa, Lupe, I definitely think of this place,” says Canseco. “I’ve been coming here for years. I’ve fallen in love here. I have cried here. There’s so many things that I’ve done here.”

Throughout the course of history, artist communities have gathered organically. Impressionists had cafes. New York City’s neo-expressionists had nightclubs. “Think of almost every innovator going back into the beginning of modern art and there are very few, if any, isolated figures that weren’t a part of the scene,” says Deitch. “You need someone else encouraging you and criticizing you. Telling you you’re not alone. In this particular group, it’s amazing how the artists connect with each other.”

After all, what do murals of injury lawyer ads, paintings on adobe, ceramic martian vessels, ’90s archival ephemera and portraits on wood panels have in common? The artists who make them, and L.A.

Guadalupe Rosales

I was gonna make a room [that evokes my childhood bedroom]. But I wanted to be more porous and more part of the show, so instead of having a drywall room, I made it a skeleton, a steel frame. I want to invoke the absence of memory or absence of experience. My whole practice has been so much about the eerie, ghostly longing of these times, rather than being so formal and rigid. I’m also bringing in my portals that I’ve been making for quite some time now, but these are new. They are engraved polished aluminum and one of the portals says lyrics of a song — “I’ll smile for my friends and cry later.” And then inside the portals, I also have some archival material like newspaper articles from the L.A. Riots, a bandanna, things that are representative of my childhood. I wanted to make it a little bit more playful.

I think people tend to group us together because of who we are and what kind of art we make and where we’re from. And we’re all different. That’s the beautiful thing about the show — that everyone is bringing something different. But then we’re gonna have some connections. We’ll be able to see that in the show. I like to think of it as this constellation — where the ring gets bigger but you’re still connected somehow.

What makes up L.A.? For me, it’s alleyways, dark corners. It’s not just these landmarks of the bar or the club. It’s more about things that resonate. A lot of the people in the show can appreciate that — they know what I’m talking about, and vice versa. Painting these billboards, or being inspired by them — we recognize that as an L.A. moment. It’s almost these gestures or clues that we drop in our practices. I think it’s so special what’s happening now, because finally, we’re being recognized. Not just as artists, but as part of culture, American culture.

Alfonso Gonzalez Jr.

The work I’ve made for the show focuses on advertisement and billboards. I have a background in advertisement. I started painting signs and then ads and billboards — not only would I paint the billboards, I would install the billboards. And even before that, when I was really young, I would paint graffiti on billboards. So I have this connection with billboards. Just observing the city, I started seeing these lawyer ads everywhere; I see way more injury lawyer ads than movies. Entertainment, luxury — these things are secondary to suing people. It’s also funny how they are all sort of targeting different demographics.

One of the works is a Mexican vaquero. A super chaka guy — he’s wearing a chain and has a Jesús Malverde on his phone. He’s taking a selfie. It’s appealing to Gen Z, Millennials. There’s a few references to specific locations. One of them uses an address for La Puente, Avocado Heights. That billboard is in conversation with Mario Ayala’s billboard — he has a billboard in the space, and I have one of the same scale basically across from [it], almost mirrored with different ads. His piece references Fontana, where he grew up. Mine references La Puente, where I grew up. I think we all grew up somewhat similarly, compared to other people in the art world. And we, for the most part, are inspired by the same things. We find ourselves at the same places, even if we don’t plan it. But it’s interesting how you can take that and then create something that looks and feels completely different.

I used to work in my backyard and in 2019, rafa did a studio visit with me. A few days later, he was like, “I keep thinking about your backyard and [how it’s] a comfortable space for us to hang out.” Usually, we’d see each other at art events or parties. It was also during a time where there was interest in some of our work. That was the first time I started getting any type of press and noticing that people would write things about me that weren’t accurate — it wasn’t the way I saw myself or it wasn’t the way we identified. rafa was like, “What do you think about us having these meetings, and barbecues and then doing an exhibition in your backyard?” We started meeting and just talking about everything — things that we could only relate to as artists, especially nonwhite artists. [The two-day carne asada and exhibition, “L.A. Fonts”], was between us. There wasn’t a curator. There was no money. I didn’t necessarily know everyone, but after that I did. It was us stepping up and saying, “Let’s organize ourselves.” And not have these other people group us together. Let’s invite the people we feel comfortable with.

With this current exhibition, [“At The Edge of the Sun,”] every part of it felt really important for us to do ourselves. If we’re going to do this, we have to do it a certain way. And because we’ve done it out of necessity [before], we’re comfortable with that, where maybe other artists don’t have the experience.

rafa esparza

I am contributing one piece, but it’s the largest scale that I’ve ever worked with with adobe. It’s a multiple panel composite that measures 10 feet high by 12 feet wide. I knew from very early on what I wanted this image to do. Now that it’s actualized, I’m just excited to share it. Excited about the conversation that could be had. It feels like it’s a piece that’s making a bunch of citations. There’s a lot of references to the knowledge building that’s happened over the course of 20 years. From very early on, this decolonial theory has been part of my politics. In 1999, or 2000, that wasn’t a popular discourse. It didn’t have the public platform that it has now. For better or for worse, it’s now something that people could look to Gaza and name what they’re seeing. So for me, this painting is in many ways a note to my younger self. I call it “Trucha,” because the person in the photo is kind of caught off guard in their bedroom. I want to think about that word, and all of the different things that it means. Watch out, be careful.

In this moment, there’s this frenzy to carry the next Latinx art show. That kind of tokenism has always existed. And it just felt like, “Why don’t we just take it over? Take over the project ourselves?” That was the consensus. There’ve been a lot of breakthrough moments in Los Angeles, specifically the last 15 years or so. That is where you see people demanding that our institutions be more inclusive. And I think having that same kind of disposition towards commercial galleries feels important, especially when you start to think of works like a collective, persevering the ways people making culture immortalize our communities, our people, our sense of aesthetics. It feels pretty major for us to just take up this space.

The mirror nature of all of us being based here, making work here, you can’t avoid it. The through lines are maybe more palpable among some peers than others. I think that’s something that’s interesting about the show: You’ll be able to see moments of convergence. And also moments where they’re like, “Oh, this is something very different.” One of the reasons why I make art is to be part of a conversation. To understand what you’re making. Understand whose shoulders you are standing on. To be able to compare our projects and our practices, but to also be able to distinguish us from one another.

Mario Ayala

I’m showing this installation of a trucker chapel and a couple of paintings. The idea originated from my own experience and relationship to truck stops, because my father is a truck driver outside of L.A. in the Inland Empire. Since I exhibited in New York, it felt like it could have a second life here. There’s maybe some common thread, visual language and history that inevitably — living and growing up in Southern California — we share. It seems normal: to want to share space. I think painting, because I consider myself more of a painter at times, can be lonesome, an isolating way of working. We’re really trying to celebrate one another outside of the spaces that we’re normally seen. Since we’ve known each other for quite some time — organized other sorts of celebrations or openings — it felt natural to direct ourselves.

Diana Yesenia Alvarado

For the last couple of years, I’ve been exploring clay and working with ceramics. Since it’s been the main material I’ve been communicating with, I felt like it was the best route to go for as an offering for this show. I started exploring a lot of vessels, and I’ve always made characters. For this one, I was thinking about the friend group, I was thinking about the context of L.A., I was thinking about the symbolism behind this show. I wanted my work to feel playful, to feel like it’s an invitation to imagine, an invitation to dream and an invitation to question these spaces. I was living in Mexico the majority of the year, and coming back, I started seeing the elements of what makes L.A. to me. Little details on the signage, on ice cream trucks. These are all things I’ve always loved and I wanted to go back to my roots of what drew me to start making, or what inspired me, in the beginning.

I don’t come from a background of anyone in my family knowing anything about art, so I feel like even if it wasn’t in my complete awareness, I was always looking for a community, or just people to connect with and speak a certain language or expression. I do feel like we’re all in conversation because a lot of us came from that background and are the first artists in our family. It’s a very special and particular thing to dedicate your life to, and we’re all so devoted to our practice. To have those passions and the resilience to continue even though sometimes it feels like odds might be against you — I think that’s a unifying factor in some of the conversations I’ve had with artists here. And when we visit each other’s studios, whether it’s subtle or very straightforward, I do think we are inspiring each other, whether we’re making paintings or weavings or ceramics.

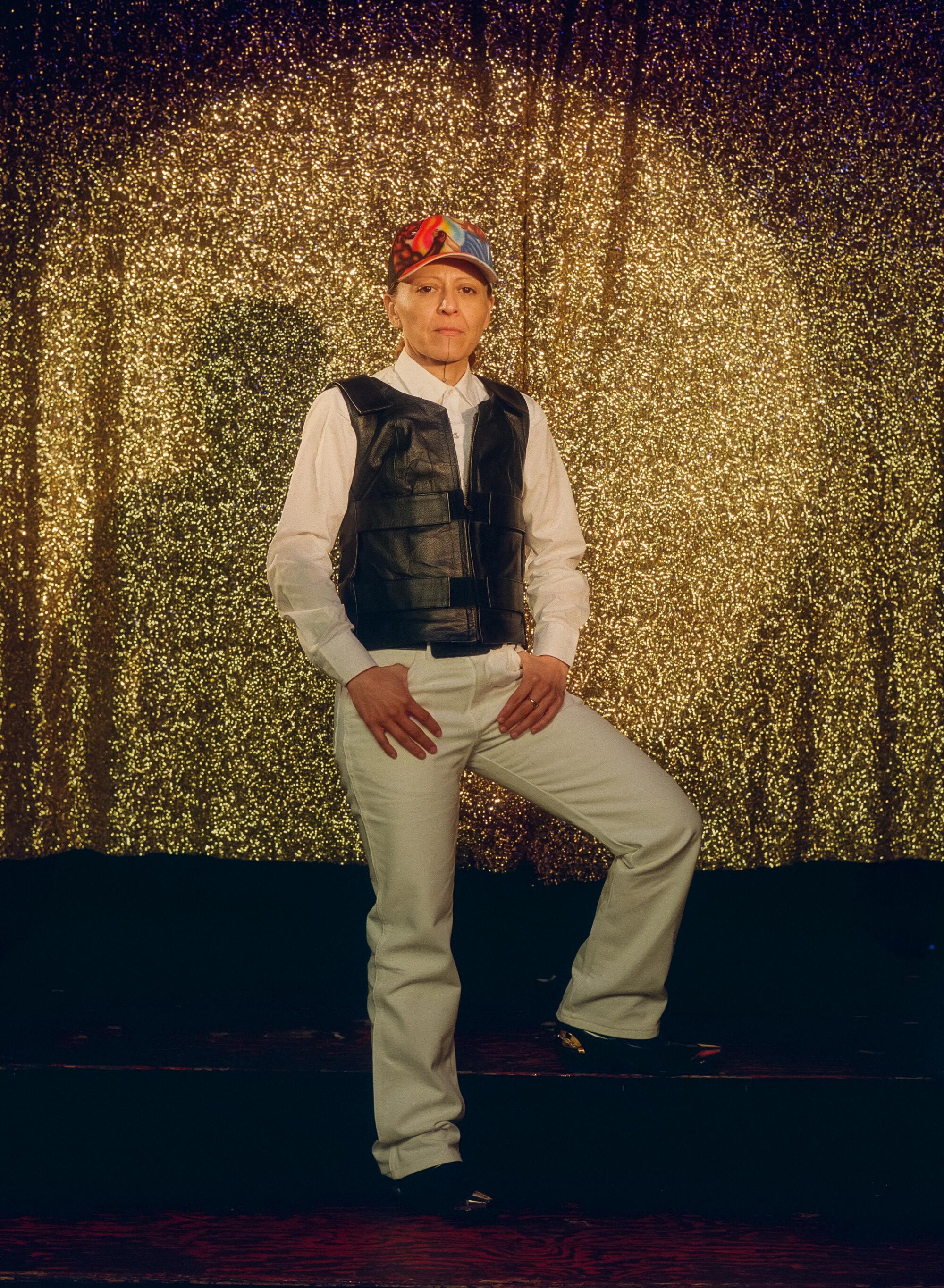

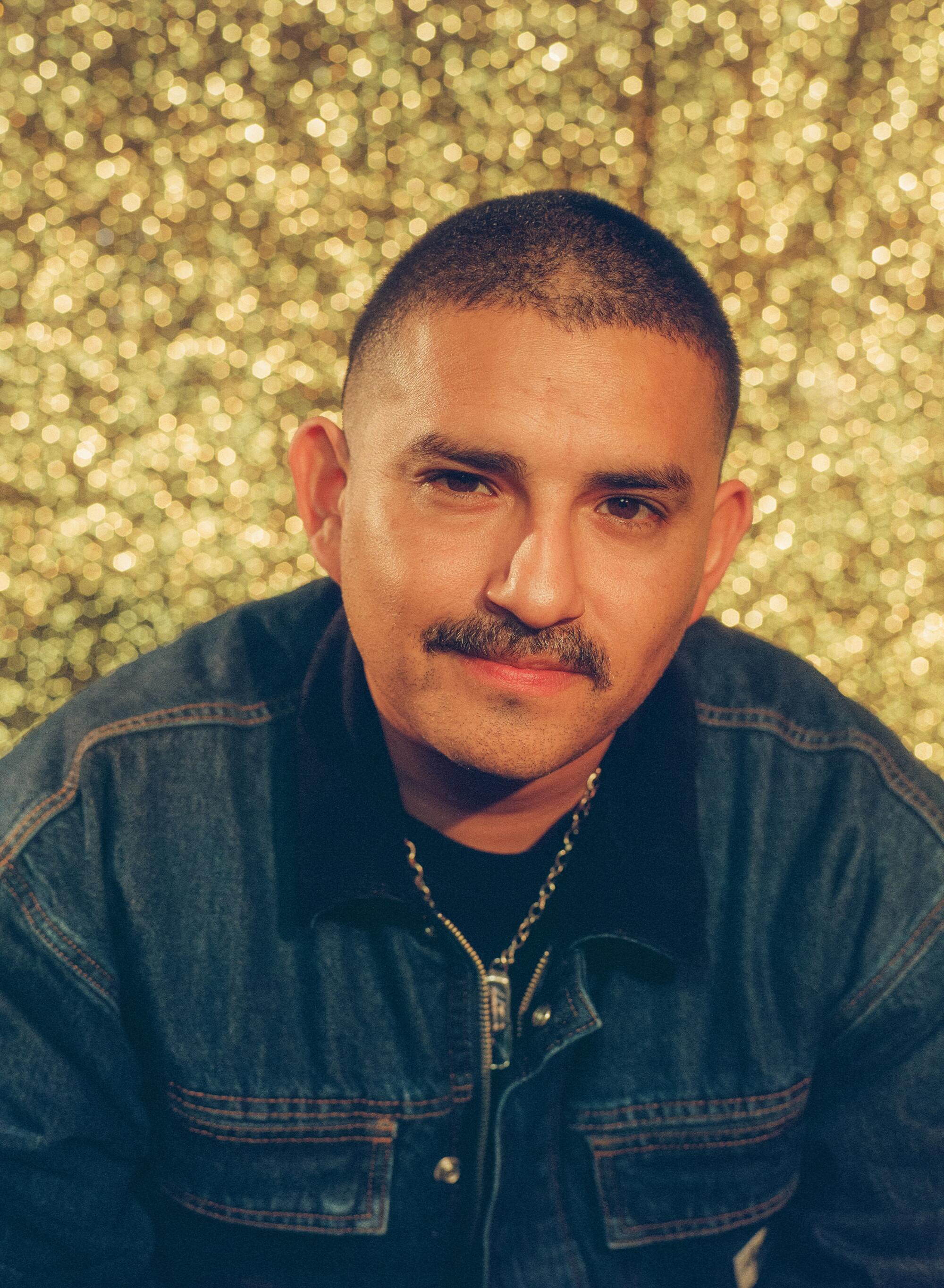

Shizu Saldamando

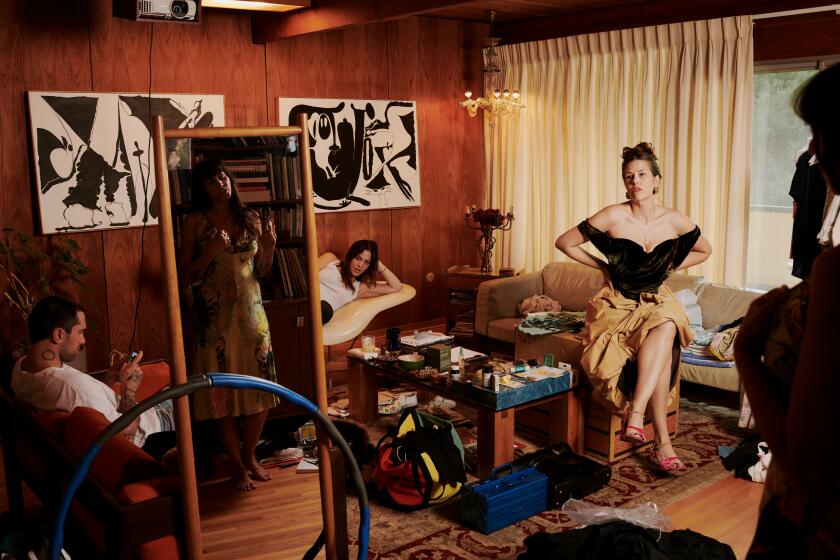

When they asked me to do the show, I was like, “Oh, well, why don’t I just do portraits of everybody in the show?” I have already painted half the people back in the day — [including] rafa in 2013. And these are people that I would want to do their portraits anyway. For us all to be in community together — I’ve never had this before. Even with “Phantom Sightings” [the 2008 exhibition of Chicano art at LACMA], it was very hetero, still tied to the institution in terms of strategizing your work to be more conceptual and subtle in terms of the overt cultural references. So this time, I feel like we’re all really extra. And we’re all very supportive of each other’s vision. We understand that there’s art in our culture, in our communities, and in our daily lives and want to honor it. We all have really similar value systems.

I actually did Gabriela Ruiz’s portrait here — I took a photo of her at New Jalisco in 2017 or 2018. I’ve always been crazy in the club. Every scene. Goth clubs. Rock en Español. I was always dancing. There’s sort of a healing that happens when you go to punk shows, socializing, and being around people where it was a safe space to be angry and to be cathartic about your pain. So my practice has always been very social in terms of gathering images. I feel so lucky to have this practice to channel the trauma and create pieces that are born out of love and admiration. And a way to honor this historical trauma that we’ve all dealt with as communities. Understanding the threads of that is so important to me and something very healing.

I’m doing the portraits because they’re really celebratory, and they are homage pieces to people and their legacies and their family histories.

Maria Maea

For most of these last two years, I’ve been really thinking about the compass. I’ve really been thinking about navigation and our ability as diasporic people to find ourselves in space and place. This piece that I’m working on right now is a compass and it uses water, because I really want to think about the functionality of my work. I’ve been in this place of trying to prototype civic projects that I’m really interested in. I think I’ve gotten this powerful privilege being in this community, to spend the last couple of years telling my story, my family story and our diaspora story as a mixed Long Beach family.

Two points of interest for me in Los Angeles are our history and relationship to water, and also our relationship to housing and the unhoused. The show has been a good container for that. I really want to think about — in a very Aquarian way — how, as artists, we really get to influence what our city develops as.

For the better part of a decade, a lot of us have been intersecting either really in close proximity or at a distance. We’ve encouraged each other, no matter how different, no matter what kind of space we can provide. We’ve always tried to be present with one another’s work. And that’s a choice. I’ve been in a lot of different kinds of communities. And this is a choice. My work couldn’t be more different than Jaime’s work. Still both measured, and still both calculated, but the results are different. With so many of these artists, I see similarities, and I see the polarities. And yet, we show up to each other’s shows. We’re all coming from different backgrounds, but at the core of it, there’s this ethos of our brown communal upbringing. I think “L.A. Fonts” — the show that happened in the back of Alfonso and Dee’s house at that time — really showed that this is a community that’s picking each other. And no matter how it goes, we’re gonna keep picking each other.

Showing at Jeffrey Deitch, there’s a lot of prestige. But how do we keep it truly reflective of our community? What are we modeling? That was a big part of why this [show] took a year to talk out. Because it wasn’t all just the front end, like, “What will we show?” But also back end: “How can we radicalize what the gallery system is?” Right now we’re in a very in vogue moment with brownness, and we want to be really mindful [about] how we’re creating structures that outlast a trend, so that it’s not just a moment but creating infrastructure for ourselves and generations after us, but also the elders that we love.

Karla Ekaterine Canseco

A lot of the conversations that we’re having are always so much about labor, or the choreographies of labor and what kind of work can get built in those spaces. A lot of us [have] built friendships doing these choreographies of labor. We’ve learned from each other so much. I may have known how to weld and I may have helped Maria, but Maria taught me how to weave. rafa has taught us how to make adobe. Gabby has taught me a lot — Gabby’s a performer that I really admire, and I have my own performance practice, too. Most of us were friends before we were peers. I think it adds another layer of trust as we all grow. This is a conversation some of us have been having for almost eight years. Working alongside each other, seeing all of us develop and evolve as artists, I think has been really beautiful.

I’m going to be showing three pieces. A lot of my work has to do with dogs and Xoloitzcuintlis, the way they have these myths around them, and the way that they’re guides and also these companions. The idea that these myths are constantly evolving — it’s something that keeps shifting and moving with what’s happening in different spaces — queering time in that way. I incorporate different materials like motor oil, the notions of tires. I want to think of the excesses of this world. [There are also] references to these pre-Columbian ceramic toys and ceramic wheels. They’re this cyborg alien figure that has already existed for a really long time.

I was born and raised in the Valley. There’s some really beautiful things about L.A. — really beautiful natural geography, but then there’s this really insane industrial geography. The way that the river has no more water and you have a freeway that actually mimics the river, the movement of water — the fastest way through the city. I think a lot of those things have a big play in my work. The contrasts of these two super powerful forces. While there’s something really dark about my work, it’s also fantastical, wondering how those things exist at the same time. It makes me think of myself as even partially machined — like these are the extensions of me. What if this machine is also my ancestor?

Gabriela Ruiz

I wanted to create a space for my work. [For the piece I’m making for the show], I painted the walls red and I have some vinyl that is going to go on the wall and then two paintings. I created these spiral shapes. I got them cut and it’s going to be the same shape mirrored on the other side and the center is going to be a plexi panel with a spiral. Then there’s going to be monitors within the plexi piece [which will be] showing some video that I’m working on right now. I love the idea of the spiral. I’m literally in a spiral right now. Everything’s a spiral.

I live in the Valley. I’m always repping the Valley, and also really inspired by my commute. I’m constantly trying to take different routes to get to my studio or going back home. Every day, I get to see the city in a different perspective. When I think about these landmarks, I think of these spaces I was brought in by friends. Places where we go after we’ve had a crazy week and we want to do something fun. You go to each other’s houses. You go to the bar. To me, these spaces are really important, especially queer spaces, because there’s not a lot of these spaces in L.A. Finding these special moments where you can unwind and celebrate each other, it’s beautiful.

We all are just very close friends in real life. And I think that plays so much in our practice: Talking, sharing information, helping each other out with different things. We have similar ideas or beliefs. Even just checking in with each other. I talk to Karla all the time. I talk to Lupe every single day, three to four times a day. You probably have this connection with your friends, now imagine your friends work with you — those conversations are still happening.

Michael Alvarez

My practice originates in portraiture and figure, but also extends to landscape, particularly social landscapes that have an Angeleno-built environment, because that’s where I come from. I’ve been doing an extension of a body of work I started in the beginning of 2008, and it all feels like it’s still part of the same vocabulary and language that I still feel a commitment to.

There’s going to be two paintings that are based on two particular parks. One of them is El Sereno Park. I grew up about six blocks away and I’ve been going to that park since I was a preteen. I grew up skateboarding, and in the early 2000s, a skate park was built. And then it was remodeled and became a hotspot. Within skateboarding, I’d be considered an old head. So I really get to experience the park at a more peaceful time. There’s a tennis court, basketball court and then skate park. A lot of times, you may have to pass through each level in order to get to the skate park. Each realm has its own particular energy, format and histories. My concept is wanting to show the different types of histories and experiences and stories that either exist or have existed in the park.

There’s an organic formulation to the communities within the show. Some people have known each other roughly 20 years, some maybe five years. There’s acknowledgment of spaces and environments within [everybody’s] work to some capacity. Navigating whatever type of art world we’re navigating, some of us felt like outliers within our own individual experiences. Upon getting familiar with each other, it helps to feel like we’re all part of something, and maybe speak in a similar language. There were a lot of conversations and meetings and check-ins. It grew out of that — where there was space for people to say what was on their mind, so that everyone could feel heard.

Ozzie Juarez

Talking about landmarks, one of my main pieces in the show [references] Bonito’s Swap Meet in MacArthur Park. I grew up in South Central, but I grew up going to MacArthur Park, because my mother worked at a clinic there. I would go, drop her off, help her out, and then go hang out. Then I lived in MacArthur Park from 2012 to 2016. I’m a swap meet freak. I go every single Sunday. It’s a place where I can find creativity and talk to people. I take photographs. It rejuvenates my mind. There’s always new things every weekend — I never go without buying anything.

There’s [a] piece in the show that came alive in three days: The painting [includes] half of the title of the show: “Edge of the Sun.” Mister Cartoon — I’ve been hanging around with [him and] his son, and they’ve been a big inspiration to the way I look at art nowadays — he blessed me by allowing me to paint a reference of his car, Penny Lane. It’s the image of Penny Lane taken by Estevan Oriol. There’s f—ing levels to this s—. It’s not just a painting. There’s histories and paying respects and love and connections and mutual respect towards each other.

I’ve been looking at everyone’s art not just as an artist, but as a curator for a long time. I’ve been looking at rafa’s work for a really long time, I’ve been looking at Alfonso’s work for a really long time, I’ve been looking at Gabby’s work. I’ve been seeing the transitions of all these artists from when they weren’t selling anything to becoming the artists that they are now. And so the work by nature is in conversation with each other just because we’re already in conversation. [T]hese schools [organically] build up if we’re talking about history. Like the ’80s in New York. We gravitate towards our tribe, we gravitate towards what we see. It’s just so natural. We know what it’s like to be a brown person in this art world. We have that strong connection between each other. And by default, we’re making work that relates to each other.

Jaime Muñoz

I have two large paintings and two small drawings [included in the show]. One of my main focuses is specific dialogue within the idea of commodity — whether it’s the commodification of the body or the spirit. My earlier work was more in dialogue with the commodification of the body and really communicating different ideas that are specific to labor and the colonial moment. With this recent work, I’m still looking at commodity, but more so as a critique of consumers. That’s the other side of it: There’s the religious side and then the capitalist side. That’s the historical context of the visual language that I’m creating.

I see the Los Angeles freeway system as one of L.A.’s biggest monuments. The history of it is really charged. Just thinking about identity politics, there’s a lot of history that I identify with [in terms of] commuting to work. What my inspiration was for my body of work was thinking about what I see when I’m on the road — try to synthesize some codes or dialogue around that visual language. I was born in L.A., but I’m not from L.A. proper — I’m from the far east side, Pomona. So I wanted to be authentic to my experience of commuting.

That’s something that I’ve been fascinated with for a long time: We all come from similar backgrounds. A lot of us come from the same heritage, similar working-class backgrounds. Because of our identities as people, there’s a lot of crossing lines between everyone’s work. It’s a trip. It’s almost a hidden highway system of information that we’re all tapping into unconsciously.

Lighting design and photo assist: Lucas Alvarado-Farrar and Saúl Barrera

Location: The New Jalisco Bar