Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Mail gets sent to the dead all the time — ads, renewal notices, unpaid bills. But if you want to send a letter to someone you’ve lost with the chance that they’ll actually receive it, there’s a box at a Los Angeles post office that carries a mysterious power.

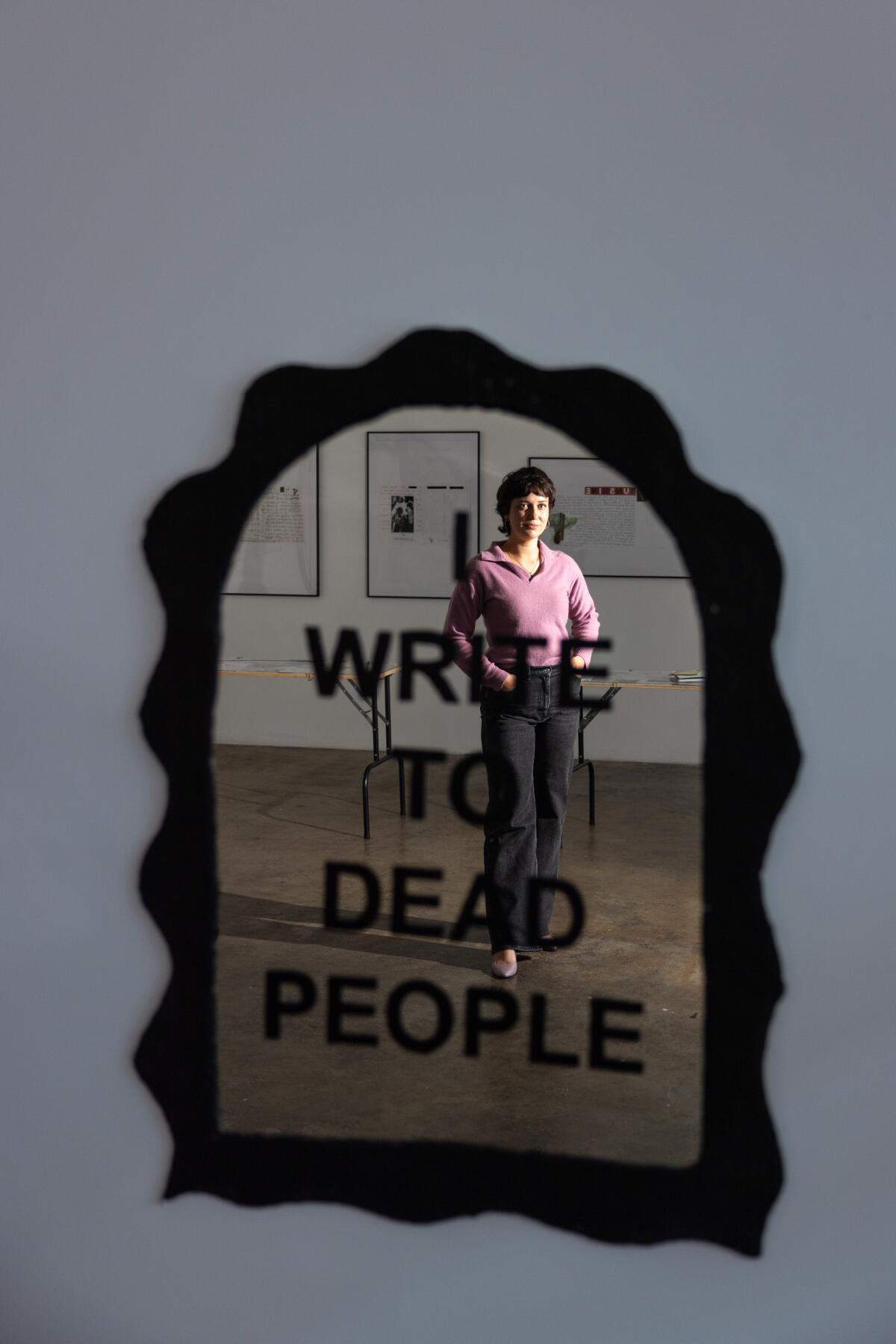

Postal Service for the Dead, started by artist Janelle Ketcher, provides the living with a way to physically send letters to those who have exited this realm. The letters are stored, and if so desired, shared with the public. Senders indicate on the back of envelopes if they’d like for the notes to remain sealed or not — leaving them blank means do not open, a heart signifies read but don’t share and a star indicates share. Postal Service for the Dead also functions as a community archive for those who have lost someone, that nation that transcends borders and dimensions, whose language is grief.

On Nov. 30, 2022, Ketcher was struck by something on what would have been her mom’s 68th birthday. “I woke up that day with this really deep urge to send her a birthday card,” Ketcher says, so she searched the internet for a way to send a letter to someone who had died, but found nothing.

Inspired by projects like the wind phone, a disconnected payphone in a garden in Ōtsuchi, Japan, where people can call the deceased, Ketcher decided to just do it herself. She opened a box at a post office in Lincoln Heights and launched an Instagram account. In the year since, dozens of people have sent letters, coming from the West Coast, the Carolinas, Florida, France and beyond.

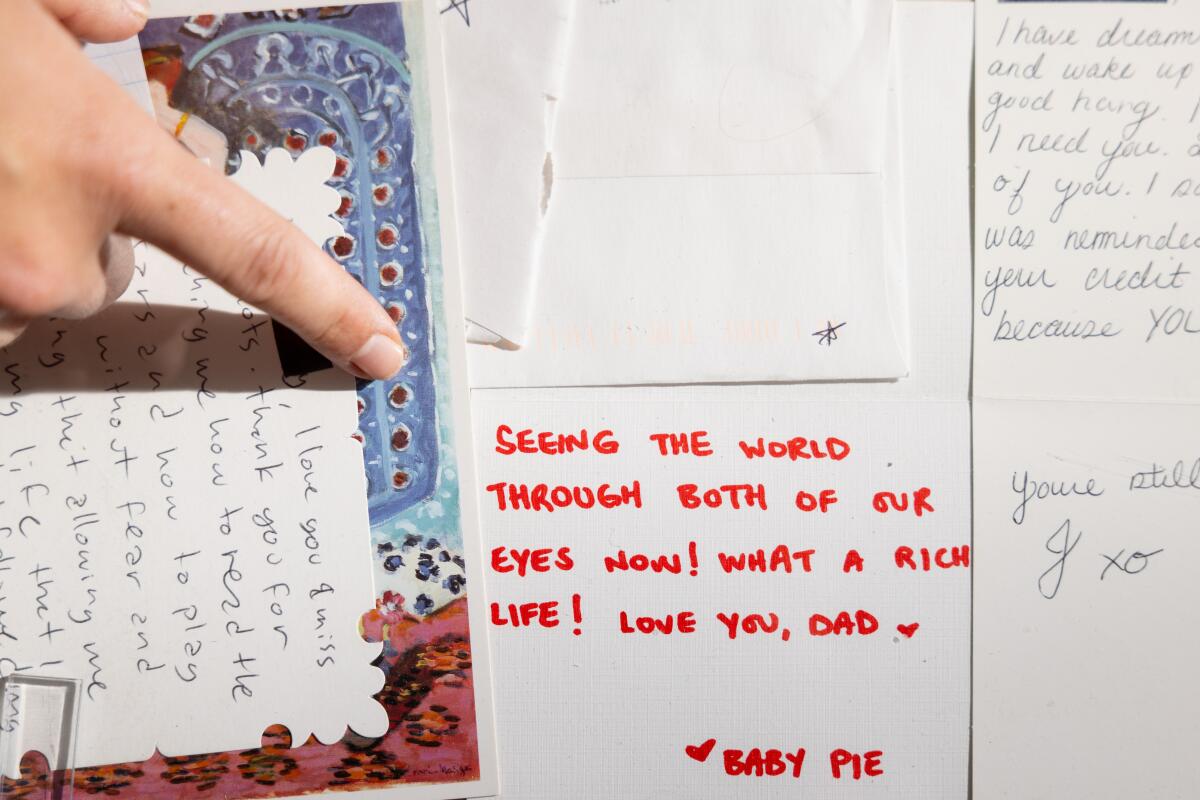

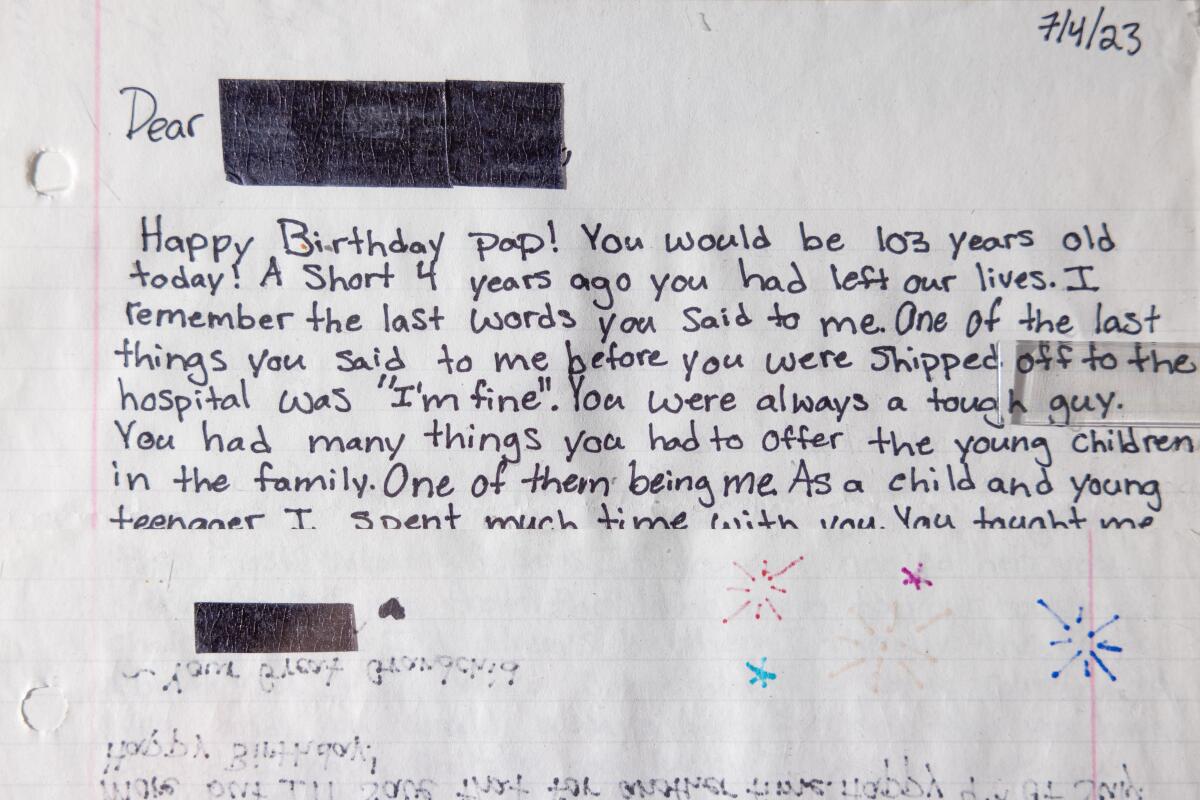

They include postcards, handwritten notes and homemade collages. There are sweet, nostalgic remembrances, memories of times had and updates on lives lived, but also letters that render the anger, confusion and despair that can accompany the death of a person close to us.

“One big thing with grief,” Ketcher says, “is that even within a family or community unit, everyone could be grieving in a super different way.”

The archive includes letters to family, friends, pets and those who are not physically gone but who are lost in other ways. Most of the letters sent via Postal Service for the Dead have been marked for sharing. Only one letter, sent in an envelope the color of terracotta, was left blank, meaning it will remain sealed and unread.

An exhibition of the letters marked sharable is currently on view by appointment at a space downtown run by Jill Schock, whose Death Doula LA provides end-of-life services. Collaboration is a big part of what Postal Service for the Dead does. In the events she hosts around the city, Ketcher includes other organizations and people in the local death care industry, such as Mortician in the Kitchen, a project by Amber Carvaly, a licensed funeral director whose work focuses on the role of food in the death and grieving process.

Ketcher is a graduate of the Kansas City Art Institute in Missouri, and for her thesis project, she focused on her mother’s aging and dying process. Her mom was diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia when Ketcher was 15, and she says “one of the things that went pretty quickly was speaking. So me and my sisters had to find ways to communicate. It was a lot of dancing and music and just leaning into whatever her reality was.”

After moving to Los Angeles in 2017, Ketcher completed various end-of-life and peer support training programs with groups like the Arts & Healing Initiative and Going With Grace. With many describing healthcare in the United States as broken, it would seem that deathcare is broken too.

“We live in a death-denying society,” says Melinda Ramos, a licensed embalmer, funeral director and crematory manager in Los Angeles.

When she tells people what she does, Ramos often receives negative reactions. “People are like, ‘Oh, that’s weird. That’s creepy,’” Ramos says. “And I’m like, ‘What’s so weird and creepy about being able to take care of someone and to honor them for their last moment with their family?’”

Our bonds with our pets are uniquely profound and losing one can bring intense grief, especially in a culture that doesn’t make space for it.

Ramos herself recently experienced back-to-back losses. Her mother, her grandmother and her pug Eli all died within a year. She sent letters to each of them via the Postal Service for the Dead. The letter to her dog included an apology for having to put him down due to terminal cancer. “I just carried a lotta guilt,” Ramos says. The letter helped her move through those feelings.

“You were by my side through the highs and lows,” Ramos wrote to Eli, “the time you walked me down the aisle to marry your papa, the sleepless nights studying for the mortuary science program, and the worst day, when my mom died of esophageal cancer. You were my little shadow.”

The morning after the car crash, I was in a horrific stupor, a waking nightmare more agonizing than anything I could have ever previously imagined.

Another letter writer, Madison, who lives in Des Moines and prefers her last name not be published, describes her late grandmother, LaVerne, as a jack of all trades. LaVerne was born in North Dakota during the Dust Bowl era of the 1930s and made violins and reupholstered furniture and sent Madison hand-painted cards with bunnies and birds on them.

“For mine, I didn’t want it to be a sad thing,” Madison says of the letter she sent. “Grief is sometimes really sad, and there are definitely moments where my grief is different from that letter. But it’s OK to remember the really happy times, even if they weren’t happy all the time.”

Madison says there’s something different about the physicality of mail. “Something about sealing a letter, the envelope, feels really final,” she says. “Putting it into words is therapeutic. I’m already having these thoughts, so I’m just writing them down, and sending them into the ether.”

Writing letters to the dead is a longstanding practice — “A lot of people burn their letters, and that can be really helpful as well,” Ketcher says — but being able to actually send them somewhere offers a strange, undefinable benefit.

And there’s something appropriate about the Postal Service for the Dead being in Los Angeles. The city’s mythology, a brightly lighted dreamscape with a dark underbelly, makes it the perfect portal between worlds.

L.A. is a complicated place to live. Does it have to be such a complicated place to scatter ashes after someone dies?

Ketcher knows that not everyone believes in an afterlife and that the letters may not be received by their intended recipients.

“I’m just a keeper,” Ketcher says of the letters. “But I do think you can continue a conversation, you can continue a connection, through storytelling.” The artist pauses, and adds, “If you receive a letter from someone you love, there is a bit of magic in that.”

Visits to the exhibition at DDLA are by appointment. A closing reception will be held from 5 to 9 p.m Dec. 30. Letters to the deceased can be sent to Sleepy Sue Studio, P.O. Box 31412, Los Angeles, CA, 90031, USA.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.