How the killing of Latasha Harlins changed South L.A., long before Black Lives Matter

Twenty-five years after the shooting death of her teen niece, Latasha Harlins, Denise Harlins urges communities to unite against racial discrimination.

- Share via

A generation ago, long before Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown and the Black Lives Matter movement, the death of Latasha Harlins lit a fuse inside Los Angeles’ African American community.

Latasha, 15, was shot in the back of the head by a Korean woman who owned a South Los Angeles liquor store. The killing was captured on a grainy security video.

On the national stage, her case was overshadowed by another video that surfaced just weeks before, the one showing Los Angeles police officers beating Rodney King.

But in Los Angeles, Latasha’s death had a profound effect in both the black and Korean communities.

For blacks, the killing became a symbol of the dangers and indifference faced by African American youths. Those feelings turned to rage when the woman who shot Harlins, Soon Ja Du, avoided jail time. That — along with the not-guilty verdicts in the King case — became a rallying cry during the 1992 Los Angeles riots.

For Korean Americans, the case prompted soul searching and debate about the rocky relationship between Korean immigrants who owned liquor stores in black communities and their customers.

“The Latasha Harlins incident made it absolutely clear that Korean Americans are not spectators to the unfolding American racial drama, nor bystanders,” said Edward J.W. Park, an Asian American studies professor at Loyola Marymount University. “They were now intimately and inextricably implicated.”

Latasha’s killing inspired songs and a book. But the memory of her death faded in a way that King’s beating never did. The King case resulted in changes over the years in how LAPD officers were allowed to use force. Latasha’s death left no standing monuments or policy changes, something that haunts her family.

“All these people came to the surface,” said her aunt, Denise Harlins. “But nothing was ever done. That still bothers me to this day.”

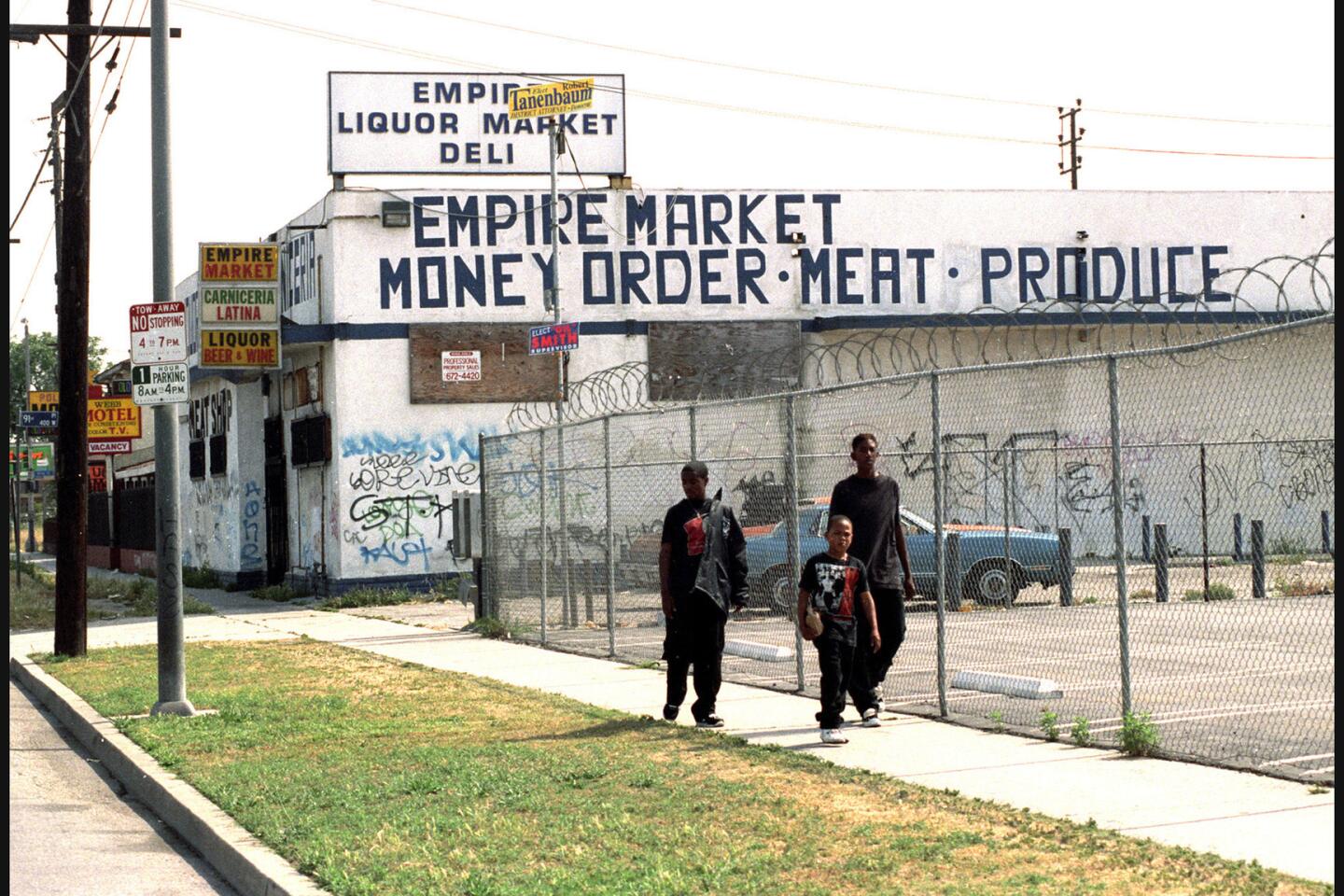

On March 16, 1991 — 25 years ago this week — Latasha walked into Empire Liquor Market and Deli in South L.A.

Du accused her of trying to steal a $1.79 bottle of orange juice. Witnesses said that Latasha, who put the orange juice in her backpack, intended to pay Du and that she had $2 in her hand. After Du grabbed her sweater, the teen punched her in the face and broke free, knocking the store owner to the ground. Latasha tossed the orange juice on the counter and walked toward the door. Du picked up a .38-caliber handgun and fired a shot into the back of the girl’s head, killing her instantly.

Police later concluded that there was “no attempt at shoplifting.”

A jury found Du guilty of voluntary manslaughter, which carried a maximum sentence of 16 years in prison. Judge Joyce A. Karlin gave her probation, 400 hours of community service and a $500 fine.

Latasha “stands as a sad symbol of criminal injustice,” writer Erin Aubry Kaplan said. “She was the most innocent of the innocents. She was 15 years old, not even legal age. A girl. The community saw this as execution.”

The case also reflected deeper tensions. African Americans complained for years that Korean merchants treated them with rudeness and contempt. Korean merchants, in turn, said that a language barrier hurt communications and that the high number of gang crimes at the time — some of which claimed the lives of Korean store owners — put them on edge.

In the weeks after Latasha’s killing, Denise Harlins launched a crusade to preserve the girl’s memory.

Harlins formed two organizations bearing her niece’s name. She invoked the teen’s name during protests, and she made plans to turn the market where Latasha was killed into a community center named after her.

Najee Ali and other activists speak at a vigil for Latasha Harlins.

In those early months, there was a swell of support from politicians, activists and residents. But as the years wore on, the rage that fueled a movement faded. The crowds at the protests thinned, dreams of a center died and Harlins felt forced to move on, although she had hoped to be able to make a difference in that system.

The Latasha Harlins Justice Committee called for Karlin, the judge who issued Du’s sentence, to step down. Activists protested at her home and on the steps of the courthouse where she worked. They collected thousands of signatures in two failed efforts to recall her. Karlin remained a judge until stepping down in 1997. She long defended her handling of Du’s case.

The committee pushed for the district attorney to appeal the sentence, which he did. A state appeals court upheld the sentence in April 1992, just a week before four officers were acquitted in the beating of King, and the ensuing riots.

Now, when the nation is again grappling with the issue of race and discrimination, Latasha is largely left out of the conversation.

At a candlelight vigil this week to mark the 25 years since her death, relatives inserted Latasha into the discussion in an attempt to keep her name alive.

“As we look at the families of Trayvon Martin and Ezell Ford, we can do the roll call” of racially charged killings, said David Bryant, co-founder of the Latasha Harlins Justice Committee. “We were like … the forerunners to all that misery. But we didn’t learn the lesson then.”

UCLA historian Brenda Stevenson said Latasha’s case remains relevant, especially with the new national debate about how the criminal justice system deals with African American young people.

“It’s not just the [police] that’s this damaged arena of the criminal justice system,” said Stevenson, author of “The Contested Murder of Latasha Harlins.”

“It is also the jury, judge and the ... prosecutor. Every level of the criminal justice system is problematic with regard to race and class, with all kinds of social barriers that tend to marginalize people.”

She said Latasha’s killing was one of the reasons that rioters burned Korean-owned stores and businesses during the riots.

Park, the professor, said that although Korean Americans differed among themselves in how they viewed Latasha’s shooting, it was “one of the most defining” moments for Los Angeles’ Korean American community.

Some Korean Americans, he said, felt that Korean merchants walked into the middle of long-simmering racial tensions and were being saddled with an unfair share of the blame. Others lamented that the killing quashed budding grass-roots efforts to bridge African American and Korean communities, including the Black-Korean Alliance, which formed in 1986. Still others were flustered that the frequent violent crimes against Korean business owners seemed not to merit much attention.

“For Korean Americans, the most confusing thing was, why doesn’t Korean life matter? When will the city mourn the lives lost and the American dreams dashed for these Korean store owners?” Park recalled. “If you run a liquor store in an inner-city community, the price you pay is, you don’t get sympathy.”

In the aftermath of the riots, there were many efforts to ease tensions between blacks and Koreans, including sensitivity training for merchants. A decade later, there was general agreement that relations had dramatically improved.

But there also were major demographic changes by then. Some Koreans got out of the liquor store business, as the city pushed to reduce the number of such businesses in heavily non-white areas.

At the same time, South L.A. saw a significant migration of blacks to suburban areas and a new influx of Latino immigrants.

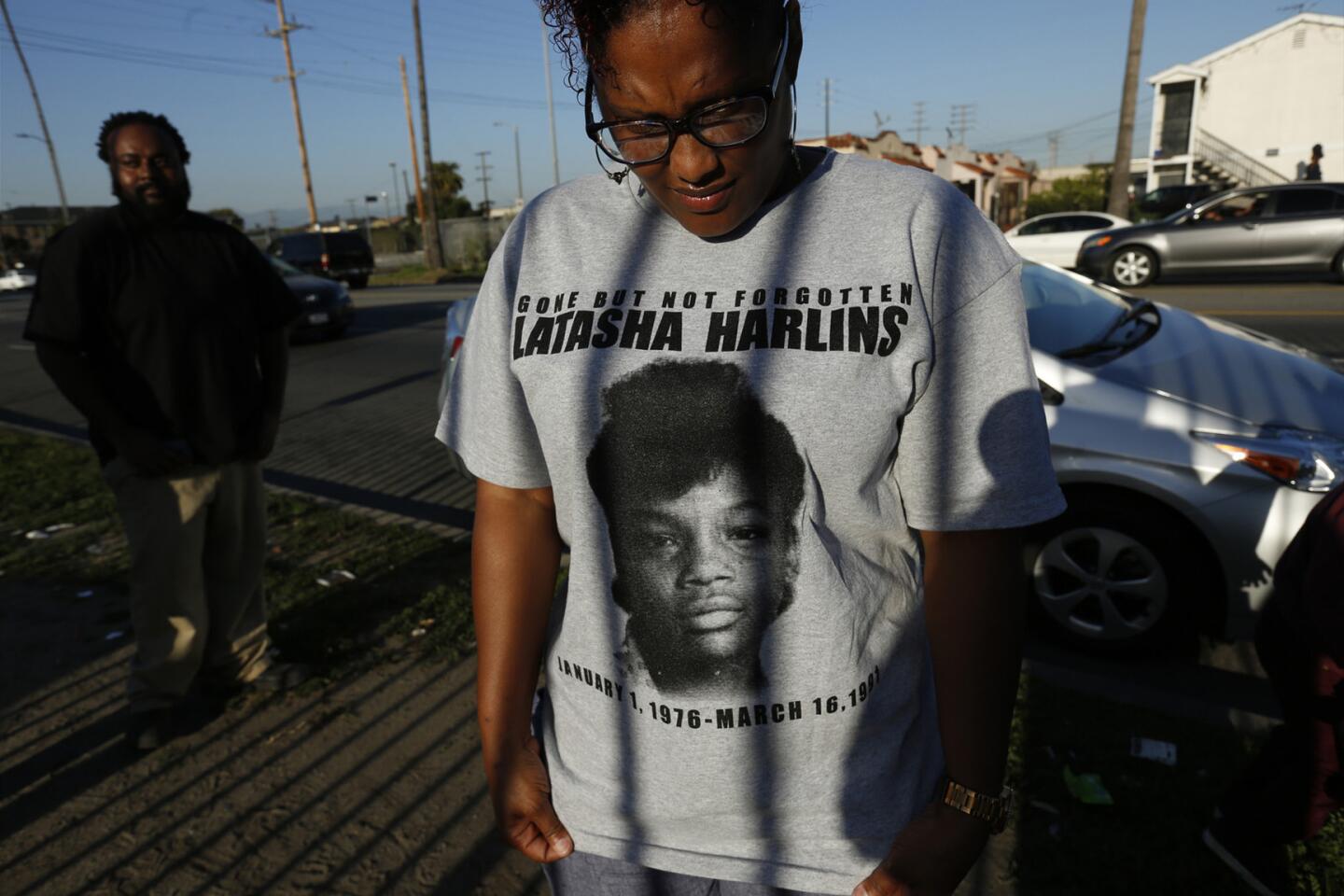

During this week’s vigil honoring Latasha, dozens of her relatives and people affected by her death gathered to celebrate her short life. Some wore black-and-gray T-shirts that said “Gone but not forgotten.”

“We are here to remember Latasha,” activist Najee Ali said as he held a bottle of orange juice. “We never forgot her here in the community.”

Times staff writer Victoria Kim contributed to this report.

Twitter: @angeljennings

ALSO

Coroner ID’s worker who fell from 53rd floor of L.A. high-rise

The earthquake expert who made Californians smarter and safer is moving on

Reservoirs are getting a big boost from ‘Miracle March’ — but the drought isn’t over yet

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.