Inside the foster care system: A bleak last stop for lost youths

- Share via

Her entrance caused a stir. A 15-year-old girl with appraising eyes and a gruff, resonant voice, she radiated bridled ambition in a room filled with children who were mostly slumped and lost.

She was dressed as if heading to a party, the red of her cropped jacket a pop of bright color against the black and white geometry of her dress. But the bandages on her arms told a different story.

Get essential California coverage

A social worker and two guards drew close for the daily inspection as she crouched to the floor to unload a bag holding her only belongings: deodorant, a package of Cup Noodles, hand cream, underwear, a brush and nail polish.

“That’s contraband. You can’t have the nail polish,” said the social worker, a clipboard pulled tightly to her chest. She was enforcing a policy aimed to prevent foster youths from using a shard of glass to harm themselves or others.

Ashley had returned for the third straight night to the foster care system’s Youth Welcome Center, an old dining hall on the campus of Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center.

The center — outfitted with couches and televisions — was designed as a comfortable waiting room for children newly removed from their families; it was intended to house them for just one night while the staff tried to place them with a foster home.

Instead, the center has evolved into a holding facility for the most difficult to place youths who have been thrown out of foster homes. No one is turned away.

The facility is the last stop for some of the most desperate and extreme cases, a stark window on the difficulties of a child protection system that is burdened with maddening bureaucracy, a shortage of foster homes and crushing demands from a growing number of troubled children.

The youths who end up here are often older teenagers, sexual minorities, mentally ill or medically fragile. A significant number are involved in prostitution.

They stay here for nights, sometimes weeks, because there are so few homes willing to take them. Sometimes, the children refuse the homes offered to them and leave to live on their own. They come back sporadically to the center for a shower and a night’s rest — a respite from a life on the streets.

Social workers, many of whom have toiled together for decades outside the public eye and often under dangerous conditions, keep the facility afloat 24 hours a day.

The Youth Welcome Center is usually off-limits to outsiders because of confidentiality laws, but a special court order allowed a Times reporter and photographer to spend time there over the course of two weeks. The order required the newspaper to withhold last names and other identifying details of children younger than 18.

On the evening Ashley’s nail polish was confiscated, a “Pirates of the Caribbean” movie blared in the background as children ate at a small dining table in one corner. Social workers made calls and typed on their computers in back rooms.

At 10 p.m., about two dozen cots were rolled out and the children slipped under the sheets.

About half a dozen staffers are always there to oversee the youths. They all maintain relentlessly calm and caring voices no matter what crisis might be erupting. Nothing is ever personal, they said. It’s the abuse and neglect talking when the children say cruel things to them.

Two of the system’s most debilitating pressures — the desperate shortage of foster homes and the swelling ranks of foster youths involved in prostitution — have conspired here to make this a place where social workers feel as though they are on a never-ending chase to find lasting foster homes for the children.

On this night, out of nearly 30 youths, only one has just entered foster care for the first time: Ruben, a small 13-year-old boy swimming in an oversized T-shirt.

Like the others, Ashley already knows the room’s daily rhythms. She ended up here after she was moved out of a group home without notice or explanation. In her anger, she banged on a window at the group home and other girls taunted her by slapping the glass as well.

“My whole point was, ‘You guys aren’t scaring me. I can hit a window too,’ ” she told one of the workers checking her in at the center run by the Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services. “It kind of backfired on me and shattered. That’s why I have these stitches on my arm.”

Ashley spent her days in the department’s Torrance office to be near the social worker who was assigned to find her a new home. The worker was too busy to see her, however, and each night, she returned in a van to the Youth Welcome Center, where social workers take over the search on nights and weekends.

“When are you guys going to finally take me back to school?” Ashley asked the employees at the door.

“That’s not our job here at the YWC,” the woman with the clipboard replied.

“That’s not fair,” said Ashley, who was two grades behind in school.

She hoped to become a choreographer or child psychologist. She said, “I want to get my education.”

::

“Everything is just full, full, full,” said social worker Deborah Heath, working in a back room that night.

Heath’s assignment all day was to place Connie Dixon, a homeless 19-year-old single mother who was returning to foster care under California’s new law extending benefits to age 21.

“I’ve tried everything. I mean, even homeless shelters until we can find something better because she’s an adult,” Heath said, flipping through a stack of papers recording more than 30 calls so far. She acknowledged the irony that foster care was supposed to spare Connie from going to a homeless shelter but the center can’t even offer that.

Demand for foster beds exceeds supply by more than 30% nationally. Forty percent of foster parents withdraw during their first year, and an additional 20% say they want out, national studies show. Those families that remain are often stuck in deep poverty themselves.

The reasons for the shortage are myriad: low reimbursement rates, more women working outside the home, foster children’s special needs and, the most commonly cited problem, the dysfunction that foster parents say they experience working with child welfare officials.

“Take me off your list. I gave up on you guys,” one foster parent told Heath during her quest to place Connie.

“Oh, how come?” she asked.

“I could never get the social worker to call me back,” he replied.

A group home said there was an opening, but a waiver from state regulators would be needed because Connie was older than 18. Heath emailed the state but never got a response. Connie stayed the night.

The next day, the waiver didn’t come again. Heath was eventually told she had to put the request on letterhead. When the waiver finally arrived, the vacancy was gone. Connie stayed a second night.

Heath senses a paralysis among workers throughout the county’s child welfare system after high-profile deaths involving children who were under the department’s supervision. Some of the deaths followed egregious errors by social workers, and the discipline that resulted has many workers worried that even small mistakes might be career ending.

“They are working off fear, intimidation and threats,” Heath said. “It’s sickening. Everyone is afraid to make a decision.”

Heath and five others in the back rooms worked at a frantic pace to make more calls. Every time a child stays at the center for 24 hours or more, they must log it as a violation of state regulations that require them to move children to a licensed foster care facility. So far, the state has declined to crack down on the county.

Heath and her colleagues also know that the longer the youths stay, the more likely it is that some will become involved in prostitution.

“Some of the kids are recruiting right in front of our eyes, and there is nothing we can do,” she said.

Near 11 p.m., Jorge Sepulveda, one of Heath’s co-workers, found a home for a girl who had not yet fallen into the street life.

Sepulveda had made more than 100 phone calls since 7 a.m. before a foster family in Fontana agreed to take 14-year-old Yurisa.

Breona, a 17-year-old at the center who social workers believed to be a recruiter for pimps, shouted, “Don’t go! You can’t make her go to placement if she don’t want to! It’s her choice!”

Yurisa locked eyes with Breona. Sepulveda stared at Breona as well, seething at the prospect of so many hours of work going to waste yet again.

Finally, Yurisa turned and walked to the van, leaving Ashley and a roomful of others who didn’t make it out.

::

Breona was the inexplicable, indomitable force beyond the reckoning of any professional here.

Bouncing from one place to the next with her hands down her boxer shorts, she sometimes paused to bring her shaved head inches away from one of the staffers, leering unblinkingly at them for a moment before moving on.

“Settle down, Breona,” the top supervisor in the room, Jackie Chandler, told her.

“You settle down. How about that?” Breona replied. The staff called her a “frequent flier” because she had spent so many nights at the center.

She knew no one could stop her from coming or going as she pleased. She said she felt they had nothing to take away that hadn’t already been lost, nor anything to give that she wanted. The few foster homes they offered, she refused.

The social workers, in turn, knew Breona would run away if they forced her to go.

Breona laughed deeply on a couch, lavishing attention and charm on children who receive little of both. In the social workers’ eyes, she was recruiting them to join her on the streets.

The center had no recourse — unless Breona’s conduct was so serious as to warrant arrest or an involuntary psychiatric hold. Breona knew not to cross the line.

Social worker Heath whispered in the ear of 18-year-old Regina Cooper, “You are the older sister. Don’t let your little brother AWOL with her. I see her over there working him.”

The next day, Regina’s brother and Ashley fled, chasing Breona and her bravado out the door. It would have been Ashley’s fourth night at the center.

At one of the dining tables, Vonie, a 19-year-old transgender woman who uses the last name Bonjour, ate a hamburger and explained that she had spent more than a week here as workers struggled to find anyone willing to provide her a home.

“For transgenders, the system is very hard. It just destroys you,” she said.

That afternoon, police brought 16-year-old Shante in handcuffs after they discovered her on the Metro Blue Line with a counterfeit $100 bill.

She had been missing from her foster home and absent from school for months. Children’s Services had petitioned the court to issue a warrant to return her to the system.

“I’m not going back to foster care. It was the worst time of my life,” she said.

Shante had two tattoos on her face: One a word in French that she didn’t understand but admired in a magazine: enfant (child).Another was simply LA because, “Well, that’s where I’m from.”

With no way to stop Shante, social workers allowed her to leave after an hour, and then called the Sheriff’s Department to file another missing person’s report and readied a petition for another warrant to bring her back to foster care.

The next morning, about 6 a.m., Breona returned with Ashley and Regina’s brother. They were hungry.

Ashley had a black eye and said that Breona and a man had beaten her as they tried to coerce her into prostitution.

The sheriff’s deputy on duty was called once more, and Ashley signed a report of her account. Breona denied it and there was no arrest.

Mike Ross, the center’s chief who carries an enormous soda from Jack in the Box throughout the day, moved Ashley quickly to a group home. Breona continued to refuse placement, and the department isolated her in another room at the hospital with one-on-one supervision.

Ross held a meeting to counsel his staff not to think of her as a monster. Many didn’t know she had been in foster care since the age of 3 after being abandoned by her mother; she had been raped and beaten.

“Every night at 9:30 she takes her meds,” he told them. “Do you think she’s doing that because of your charm and wit, your intimidation or the fact that she’s afraid of your authority? No, she needs to quiet the demons in her head so she takes them on her own.”

At the dining table, Brittany, a 16-year-old methamphetamine user, was coming off a high; she was agitated and twitching.

“All you need to know is that I hate this place and I hate the law,” she told the social worker assigned to find her a home. “The law is stupid because it says that just because you’re a juvenile, you can’t take care of yourself.… Look at me. I’m still alive.”

She had lived for months behind a tennis court in a city park, she said.

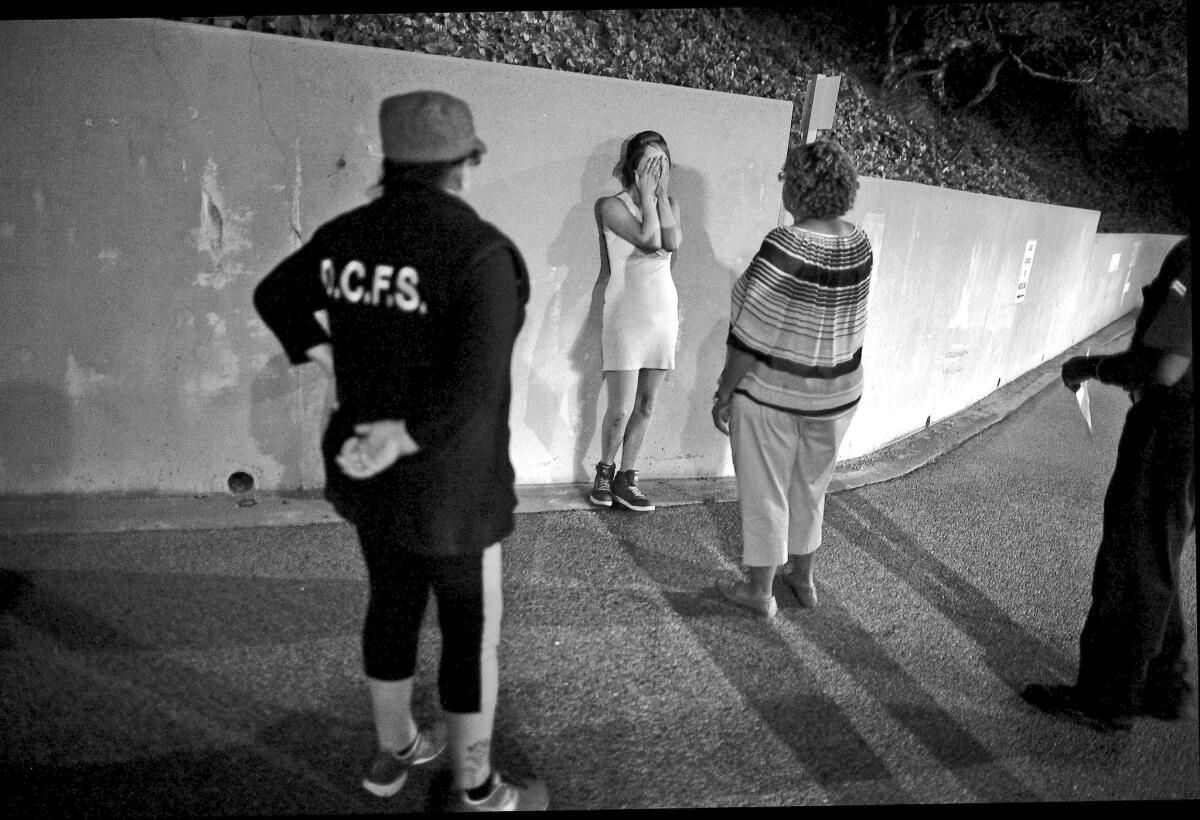

Social workers brought plate after plate of food to her table, hoping to keep her here long enough to coax her into a home. Then, at 10 p.m. when it came time to turn out the lights and shut off the television, she bolted into the night in her short dress and backward baseball cap.

Half a dozen social workers rushed out the door calling her name. A sheriff’s patrol car blocked the road and officers threatened juvenile hall if she left. It was a bluff — Brittany hadn’t committed a crime to warrant arrest.

For over an hour, they pleaded with her to come back inside, offering her a radio, the chance to sleep on the basketball courts and see the stars. Anything.

“Keep trying, bitch,” she said, plugging her ears and sobbing.

Yards away, social workers pleaded with the sheriff’s deputies to place her under a psychiatric hold, but they said she hadn’t exhibited any behavior that was a clear threat to herself or others.

The staff argued that Brittany fit the profile for a sexually exploited youth — and that this should give the deputies reason to detain her. The officers wouldn’t budge.

In exhaustion, Sarah Padilla, a 30-year veteran of the department, finally told her, “You know, I’m starving. I’m going to McDonald’s to go get something to eat. Can I buy you something?”

To everyone’s surprise, it worked. Brittany said she would like two wraps, fries and a diet Coke.

By the time Padilla returned with the food, Brittany was asleep inside the center, off the streets for at least one night.

Follow @gtherolf for breaking news about the foster care system.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.