Did City of Industry pay for idle trucks?

Under a contract with the City of Industry, Zerep Management Corp. was responsible for services such as street cleanup and graffiti removal. The contract was terminated last year.

- Share via

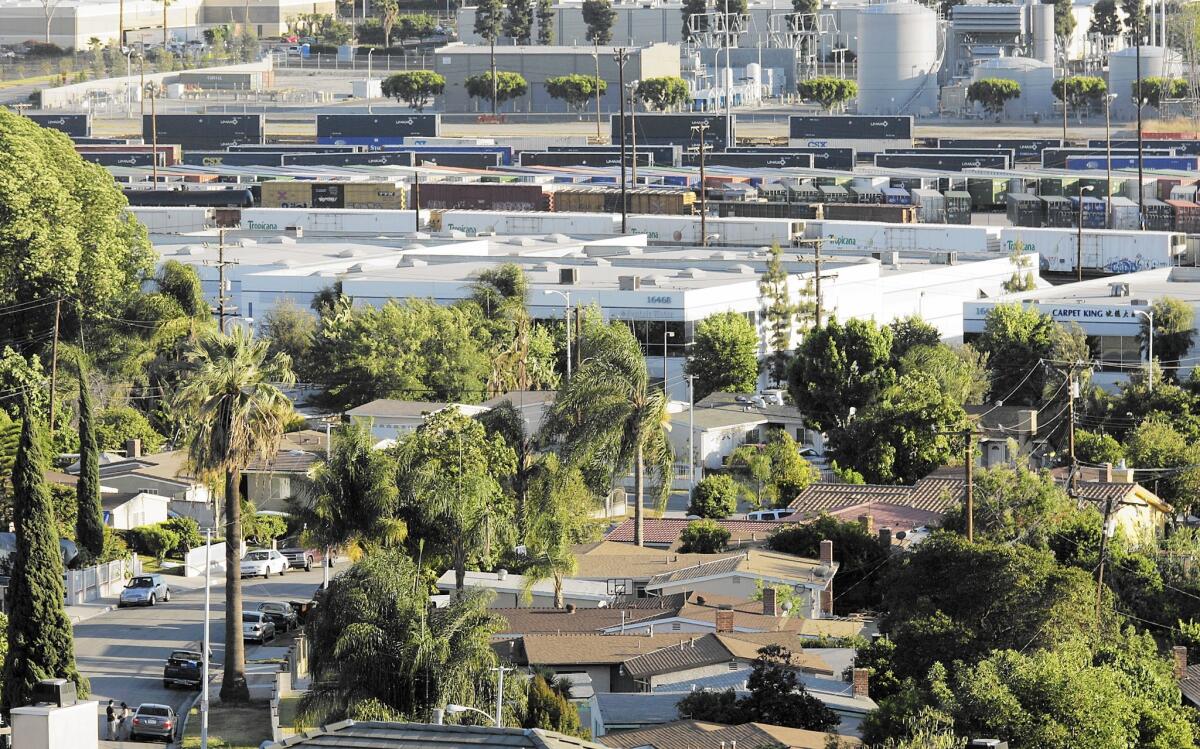

Week after week, street maintenance crews crisscrossed the City of Industry with a fleet of sweepers, pickup trucks, dump trucks, utility trucks, a boom truck, a water truck and two tractors.

That’s what the city paid for, anyway, under its decades-long contract with Zerep Management Corp., a company owned by former Mayor David Perez and his family.

Whether it got its money’s worth is another matter — and the subject of separate investigations by the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office and the state controller, as well as a civil lawsuit brought by the city against Perez and his relatives.

Zerep’s maintenance and miscellaneous services contract, which the city terminated last September after 34 years, authorized the company to charge for vehicles and equipment based on their hours of use. But The Times’ review of invoices Zerep submitted to the city suggests that the company routinely billed the machines for more hours than there were people available to operate them.

In the first week of January 2012, for example, Zerep charged the city for 683 hours for trucks and other equipment for the street crews, but rang up only 328 hours of manpower, invoices show. Not counting a sweeper and mower that included operators’ time, the city paid for nearly 300 hours for vehicles and machines that apparently were unmanned and idle.

The lopsided machinery-to-manpower ratio occurred throughout that year and others, invoices show.

The city’s lawsuit, filed in May, accuses Perez, his companies and four nephews of fraudulently collecting millions of dollars through unauthorized work and false or inflated invoices. It alleges the Perezes engaged in “extensive public corruption and personal profiteering,” in part by billing the city for “services never performed” and “rental equipment that was never used.”

City Manager Kevin Radecki, who for years regularly approved payments to Zerep before ultimately moving to cancel the contract, declined repeated requests for an interview. City Atty. Michele Vadon also declined.

Perez attorney Stephen Larson called the lawsuit a politically motivated “hatchet job” on the family, whose Industry roots and financial clout date to the 1950s. Perez’s power waned after he quit as mayor in 2012, but it might have resurged Tuesday with the election of three City Council candidates he supported.

Larson disputed the false-billing allegations, saying that all work “was billed in accordance with the contract.” He attributed the sometimes-large gap between labor hours and machinery hours to Zerep’s long-standing practice of billing the city for vehicles and equipment kept on “standby,” in case they were needed.

“In terms of reserving equipment, this practice by mutual agreement with city officials was in place since the inception of the contract,” he said. “The city for its part received exclusive use of Zerep equipment, available 24/7.... That provides the city with the comfort of knowing that it doesn’t have to scramble to find available equipment, or compete with others to secure it.”

It’s not clear how much Zerep billed for machines that weren’t used. Hundreds of invoices reviewed by The Times do not identify any of the hourly equipment charges as “standby” time. Nor does the contract provide for standby charges, or anything other than hourly rental rates.

When asked to cite the specific authorization for Zerep’s standby charges and to name the city officials who agreed to pay them, Larson offered no response.

One indication that not everyone was on board with the practice emerged in 2014, when the city began demanding detailed invoices for Zerep’s work — and assurances that standby fees were not charged. The new bills included the disclaimer: “Contractor’s equipment listed is used to support tasks and billed by the hour, as per contract, for time used and does not include any standby time.”

Zerep’s billings for street sweeping and other services were thrust into public view in April, when KPMG auditors brought in to review records after Perez resigned reported that his family’s businesses had reaped $326 million from city contracts since 1995. They found that the companies’ invoices lacked detailed descriptions of the work that was billed.

“Without supporting documents or detailed description of the services rendered, it is nearly impossible to determine with absolute certainty that the labor and equipment costs as identified on the invoice are reasonable, accurate and commensurate with the work performed,” the auditors’ report noted.

Larson also called the KPMG review a “hatchet job” and said the Perezes have hired experts to conduct their own forensic audit.

For most of the last three decades, as the provider of such services as building and landscape maintenance, graffiti removal and weed abatement, Zerep had wide latitude in choosing the work it performed in the San Gabriel Valley industrial suburb east of Los Angeles.

Larson said that was because Zerep served as Industry’s “de facto municipal maintenance services department.” The benefits to the city included that it bore no insurance burden or other expenses for the company’s workers or equipment, he said.

The arrangement did not come cheap: The city paid $28 million for vehicle and equipment rentals from 2003 to 2014, including $4.9 million just for lawn mowers, at up to $237 an hour.

Zerep billings included $15.6 million over the same period for street cleanup. That works out to about $118,200 a month, auditors said, more than seven times the amount charged by R.F. Dickson Co., the city’s new street-sweeping contractor.

Dickson charges $201,000 a year to scrub all 65 miles of Industry’s thoroughfares and its municipal parking lots, according to city records. Zerep charged more than that just for the parking lots, records show.

Dickson cleans Industry streets with a single sweeper, which it runs for 40 to 50 hours a week, including parking lots. Zerep billed about twice as many sweeper hours each week, not counting the parking lots, after steadily increasing them from 40 in 2010 to 80 in 2013, during a time when the dimensions of the 12-square-mile city did not change significantly.

Last year alone, Zerep collected $1.6 million for street maintenance, including $158,000 for a five-week period just before its contract was canceled. It billed an average of more than 650 hours a week for labor during that stretch — the equivalent of 16 full-time employees.

Larson defended the billings, saying that Dickson has only a “narrow” contract to sweep streets, while Zerep’s work included minor road and sidewalk repairs, graffiti cleanup, hand-watering of some plants, litter removal, fixing street lights and replacing street signs.

Zerep also billed for many of the same types of services under separate invoicing categories such as “graffiti removal” and “sign installation and repair.” Larson said the company reconciled man-hours and time cards to prevent double billing.

Twitter: @kchristensenLAT

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.