San Bernardino brothers: Selling homes, chasing dreams, seeing possibilities

- Share via

As kids, Jose and Ricardo Ponce lived in a bleak one-bedroom apartment, shared by as many as 10 relatives at a time, on the west side of San Bernardino.

Outside, sirens screamed, helicopters hovered and gangs rampaged. A man drove up to the house across the street one day and shot his wife dead, and the boys saw the pool of blood on the sidewalk. Two doors away from the Ponces, a drive-by left two men slumped against a car, waiting for a ride to the morgue.

Today, Jose is 34 and Ricardo is 32. They are as inseparable now as they were when they ran with tagging crews half the night, until their exhausted single mother would return from her late shift at an onion packing plant, track them down and drag them home — not that she was always able to keep them out of juvenile hall.

They still travel with paint, but now it’s for blotting out graffiti on houses they’ve bought to flip or rent.

Ponce & Ponce Realty opened for business five years ago, and the first person the brothers hired was their mother, who once, after an intruder showed up, had led them away from their home clutching a .25-caliber pistol.

Jose and Ricardo Ponce are selling homes, chasing dreams, seeing the possibilities in San Bernardino.

Mom worked hard and when the boys finally grew up they took her cue, hustling their way out of poverty and into the shrunken middle class of one of the most distressed regions in California — a place so economically damaged that $200,000 will buy you a nice 3 and 2 with a fenced-in yard.

For Ponce & Ponce, even bad times can bring brisk business. Foreclosures, short sales, people fleeing, people moving in because they can’t afford anything else. The brothers have a stream of clients who grew up like they did, hoping for something better in a city that was given an “All-America City” designation in the ‘70s but seems to have been digging out ever since.

From massive job losses.

From crippling poverty and crime.

From bankruptcy.

From the deadliest act of terrorism in the U.S. since 9/11.

**

The Ponce & Ponce office, in a neighborhood of shuttered chain restaurants, is roughly a mile from where 14 innocent people were slaughtered by Muslim extremists on Dec. 2.

“I’ve never seen so many helicopters,” says Jose.

Why San Bernardino? Just because. If a meteor fell out of the sky, it would find San Bernardino.

Even before becoming known as the site of a massacre, “Berdoo” wasn’t an easy sell.

“We have clients from all over who say no, no, no to San Bernardino, but it’s all they can afford,” says Ricardo. He estimates that 90% of the people who come to them with dreams of home ownership don’t qualify for a loan.

“I tell them San Bernardino is like any other town. It has some nice areas and some rough areas, like everywhere else.”

But buyers prefer Rialto and Rancho Cucamonga to the west, Redlands and Yucaipa to the east.

In Colton one day, the Ponce brothers meet with Everardo Jimenez, who lost his pressman job of 26 years when the Pennysaver went under. Jimenez, 60, is listing his two-story tract house because he can’t find work and can’t handle the mortgage. His daughter lives with him, and he wants her to be safe. He thinks the smart move is to buy a mobile home.

Where?

“Anywhere but San Bernardino,” Jimenez says.

On another afternoon, a couple walk into the Ponce & Ponce office with their two young children and tell Ricardo they’d like to buy a house in Fontana. Something in the $250,000 range, with a fenced-in yard.

“We think we’re ready for it,” says the wife.

But she doesn’t have a job, her husband’s warehouse work pays just $30,000 a year, and they won’t have a down payment until they get tax returns in the spring. She might, however, be able to get her father to co-sign a loan.

“Fontana is a very competitive market,” says Ricardo, trying to be polite.

When they leave, Ricardo tells me they were typical clients. If only people’s bank accounts were as big as their dreams.

“A lot of these stories that come through here, I can relate to them,” says Jose, who has seen people weep when they enter the first home they’ve ever owned.

Ricardo can barely talk about how easy it is to relate.

**

Touring San Bernardino is like looking at negatives of old photographs. Something solid was there once, but only traces and shadows remain. Military, steel and rail jobs disappeared.

Today, two of the region’s biggest employers, the San Manuel Casino and Patton State Hospital — a fenced corral for the criminally insane — are in the business of false hope and incurable disease.

To me, this economic reality says something about a greater economic divide.

This year, I’ve written about someone buying a $35-million house in Beverly Hills to knock it down and build another, and I’ve written about a shoe repairman living in a van in Echo Park.

I’ve written about someone pumping 1,300 gallons of water an hour in Bel Air, and a woman in South Los Angeles who went more than a year without running water when she fell behind on her utility bill.

In San Bernardino, the castles and compounds of casino operators are perched on the foothills above a city in which transients, dealers and prostitutes parade along Baseline Boulevard, and abandoned buildings beg for a date with a wrecking ball.

The Ponce brothers sell San Bernardino, so they have to believe in its ability to help people like them close the wealth gap.

The brothers’ cousin is their receptionist. When it’s time to show a house, their mother is their cleanup specialist. Two childhood buddies also work for them. John Abad, their sons’ wrestling coach, is one of their clients, and the Ponces think they’ve found him the perfect house.

Abad wants to stop throwing money at a $550-a-month apartment in a rough downtown area and invest in a three-bedroom rancher for around $240,000. He’d take on renters and live in the guest house.

Not far from that home, on the north side of town, the Ponces show me a three-bedroom house they bought to rehab. It reeked of rat urine and feces. But now it’s beginning to look like a house someone might want to live in.

Jose introduces me to the mustachioed construction crew chief, Henry Arriola, 65.

“He was our Little League baseball coach,” Jose says.

Arriola had his own general contracting firm for years, but it folded in 2012.

“I used to make $200 a day, and now jobs are hard to come by and nobody wants to pay you,” says Arriola. Lately, he’s been getting advice from the Ponces about how to break into real estate.

“Now they’re coaching me,” he says.

The brothers are also coaching Jason Ortega, a guy they’ve known since he was a westside tough, like them.

Jose spotted Ortega, an addict, living under a bridge several months ago.

“I used to look up to him because he was strong,” Jose says. “I told him, ‘Man, you ... going to let a weak drug beat you like this?”

Ortega picks up the story: “He said he needed someone to watch his property.” Now Ortega lives with his dog Scarface in houses the Ponces are flipping. By night, he’s a watchman. By day, he’s helping with a rehab they bought for $70,000, next to a towing yard, two blocks from where they all grew up.

If not for the Ponces, Ortega, says, he’d probably still be under that bridge. As for the way in which the brothers reinvented themselves, he says:

“Never saw it coming.”

**

“It was hard, just being broke,” Ricardo says of his childhood.

Their dad was not around. Their mother raised five children.

“There were times,” says Jose, “when she tried to step in for us, and my uncles would beat her up in front of us.”

Why?

It’s just the way it was, Jose and Ricardo say.

On a visit to Ponce & Ponce, Rosa Murillo listens to her boys and rolls her eyes at times.

“One time I had a marijuana plant and she asked, ‘What is that?’” says Jose.

He told her he was growing flowers for her.

Even now, 20 years later, Murillo looks as though she wants to send Jose to his room.

“There was a lot of fighting, a lot of smoking,” says Jose. “And she thought we’d be stuck with that for the rest of our lives.”

Jose quit high school and worked in construction, parlaying that into a job checking on the condition of homes for prospective buyers.

Soon he was studying real estate, and Ricardo followed him. They were licensed and working for established companies before they were out of their teens.

The brothers did well and lived high, setting themselves up for a fall when housing crashed. They made mistakes, lost money, watched an investment in a gym go bust. Then they started a company through which they own and manage rental property, flip houses and represent both sellers and buyers.

Today Jose and his wife have three kids and live in a house on three acres in Yucaipa.

Ricardo and his girlfriend have four kids and live in East Highland, with a small stable and barn on the property.

Their phones ring all day and into the night. The brothers are jugglers, 10 or 15 deals airborne at any given time.

Even now, they fret, wondering what another crash would do to them.

The goal, said Jose, is to get to where “we don’t have to worry about our kids ever living on the street. Or living like we did.”

**

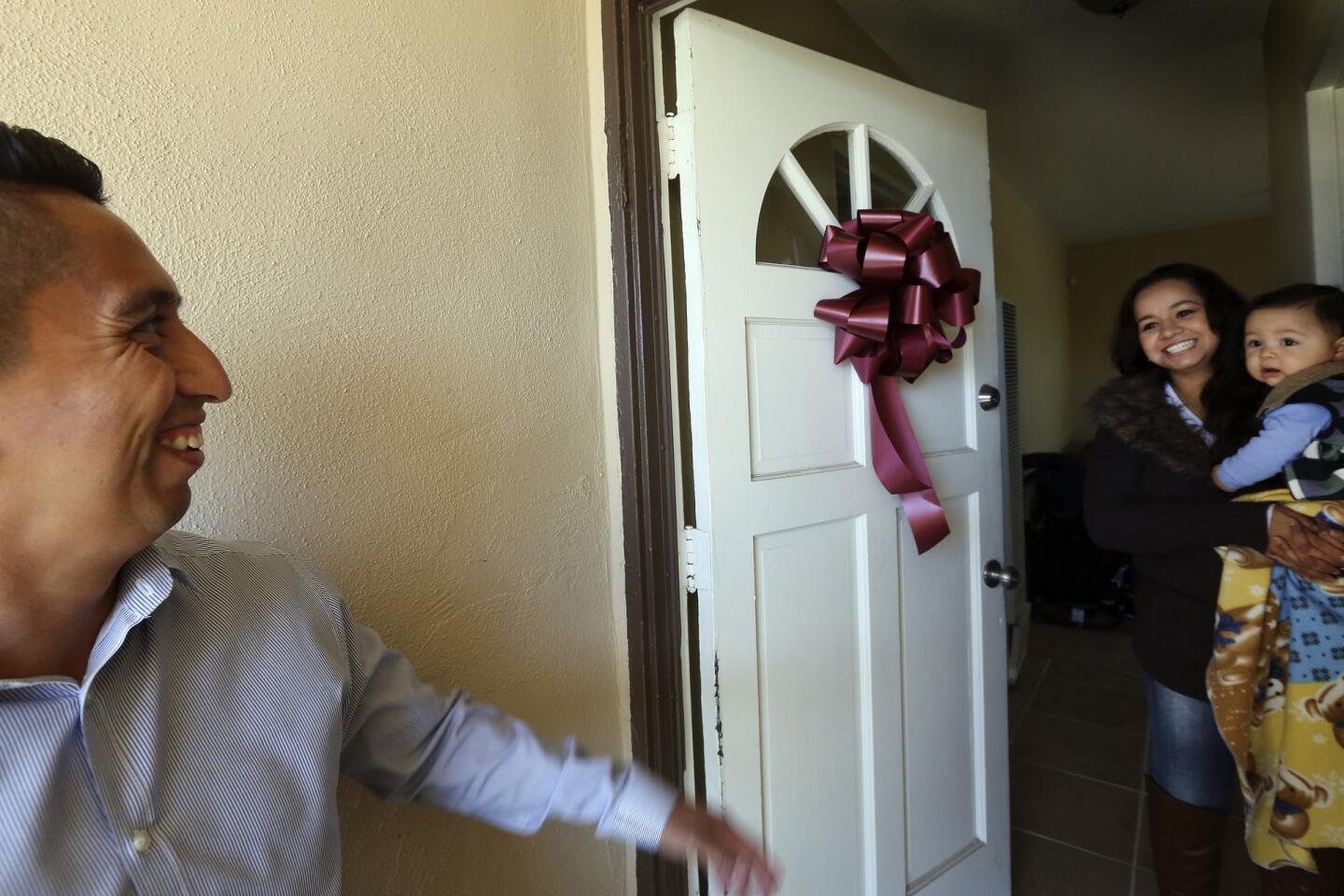

Edgar and Emilia Mendoza saved for three years, trying to make the jump from renters to homeowners. Mira Loma was their first choice; San Bernardino was what they could afford.

Edgar makes $20 an hour delivering Arrowhead water. A $7,000 down payment got them and their two kids into a three-bedroom house in a sketchy part of town, with a tangerine tree out back. The price was $202,000, and they moved in last week.

“It feels nice,” says Emilia.

Amy and Gilbert Flores, who have three children, are desperate to leave the same general area the Mendozas just moved into. Their kids have bikes that never roll out of the garage, because it’s too dangerous out there.

That’s the business he’s in, Ricardo says. People move in, people move out, chasing different dreams.

Ricardo took the Flores family to see some listings above the 210 Freeway, where people keep their houses nice, the crime rate is lower and the San Bernardino of old is not an illusion.

The one they liked best was a three-bedroom on a leafy street, with a swimming pool and a $284,900 price tag.

“I love this house,” Amy says in the evening chill as her family gathers outside.

The kids shiver, and I can’t tell whether that’s from the cold or from anticipation of the possibility in front of them.

Nearby houses are aglow with Christmas lights.

“It’s not a dream so much as a goal,” Gilbert, a welder, says of living on the north side.

“It’s all about security for our kids,” says Amy, a surgery scheduler at a hospital.

Jose loaned them some cash to rehab their house, which they just sold for $170,000. If their mother can sell her mobile home and they pool their money, maybe they’ll be living here.

The family tours the house, starting in the kitchen, out to the pool, then back to the suite that would be the mother’s. She likes it.

Back outside, sirens wail. But not for the usual reasons. A parade of decorated firetrucks, hot rods and classic cars rolls through the nearby intersection. It’s the annual Ho Ho Parade, with Santa Claus bringing up the rear.

For a few moments, all is right in San Bernardino, all-American city.

Twitter: @LATstevelopez

MORE COLUMNS FROM STEVE LOPEZ

Rosy jobs numbers blind us to the bleak reality of the ‘real economy’

Three stories of hardship put a face on L.A.’s exorbitant housing costs

Cash buyers and premium prices leave middle-class home seekers locked out

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.