For a brief, shining moment, Times Mirror Square was L.A.’s Camelot

- Share via

The headlines from Washington — Nixon and the Watergate hearings — seemed far away as guests strolled through the new corporate headquarters for Times Mirror Co.

Dorothy Buffum Chandler accompanied Mayor Tom Bradley and his wife, Ethel, through the executive dining rooms, named for the Picassos, Tamayos and Steinbergs on the walls. Architect William Pereira chatted with colleagues in the landscaped atrium beneath its high peaked skylight.

“No one would believe newspaper people work here,” said Edie Wasserman, wife of Hollywood executive Lew Wasserman.

Norman Chandler, the former publisher and chairman of Times Mirror’s executive committee, kept a low profile — his cancer well advanced by now — but the evening belonged to his wife, Buff. Dressed in a moire taffeta evening shirt and long purple skirt, she entertained as if this were her home.

“People look at the Times Mirror era as Camelot,” Stephen Meier, who joined the company’s communication department in 1977, said recently.

Memory often adds luster to prosperous times. Still, Camelot in 1973 — Times Mirror Co. with its flagship newspaper, the Los Angeles Times — seemed poised for national regard.

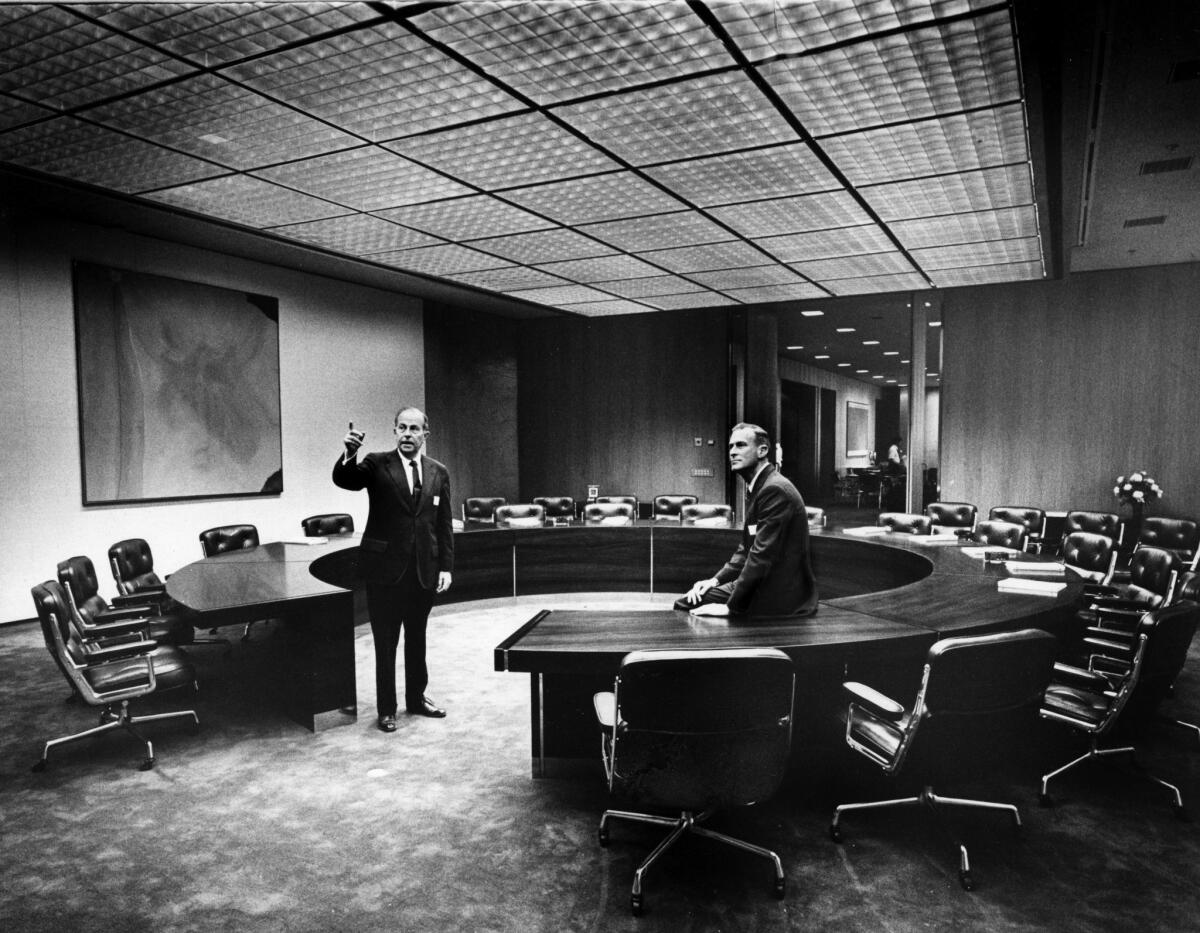

Fittingly it had its Round Table, as aviation executive Lee Atwood noted on that summer evening, a comment overheard by the paper’s society editor.

Dominating the boardroom was a rosewood ring table, shaped like a doughnut, 19 feet in diameter. In the middle, embossed in the carpet, was the corporate logo with its eagle silhouette.

Over the years, the lights of Times Mirror burned bright, then flickered and dimmed, finally extinguished when the Chandler family sold the company to Chicago-based Tribune Co. in 2000.

After rocky years that led to Tribune’s bankruptcy and reorganization, Times Mirror Square was sold to a Canadian real estate developer, Onni Group. Billionaire Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong purchased The Times earlier this year.

“The next millennium begins,” he wrote in a tweet after the “Los Angeles Times” sign was lifted onto the roof of the company’s new headquarters in El Segundo.

Onni, he explained to the staff, wanted to increase the rent by $1 million a month on the offices downtown, an amount incompatible with his desire to build a modern newsroom.

With moving vans at the curb and a July 31 deadline to be out of the building, 800 employees began a slow withdrawal — some filling Instagram and Twitter feeds with historic photos, architectural samplings, even shots of colleagues’ cubicles, nostalgia a good cover for loss.

Times Mirror Square was home, no matter the unsentimental truths that had driven the business out of downtown.

Not long after escrow closed on the property in 2016, the building manager mounted a black-and-white photo mural in the elevator lobby. Looking east at night, it shows the clock face of the Times building and the blazing lights of City Hall, circa 1970.

This reminder of that vanished era suggested that Times Mirror Square — now branded Onni Times Square — had become an object of historical regard, a novelty for tenants and guests to consider as they waited for their elevator to arrive.

But for those who worked there, Times Mirror Square was a place where history was both recorded and made. Certainly that was the ambition of regional booster and union foe Gen. Harrison Gray Otis when he ran The Times more than 100 years ago, slinging lead by day and tramping home at night with a Winchester under his arm.

His son-in-law and successor, Harry Chandler, took a more button-down approach. Dropping $4.5 million on a new building at 1st and Spring streets — adjacent to the still-standing ruins of the Times building destroyed by union organizers and 16 sticks of dynamite — Chandler instructed his architect, Gordon B. Kaufmann, to build “a suitable newspaper plant and a monument to our city.”

Finished in 1935 as if the Depression were just an inconvenience, Kaufmann’s monument — short and stocky, like a tombstone for the 21 victims of the 1910 bombing and fire — made a statement: The Times wasn’t going anywhere.

Neither terrorists nor economic downturn could alter its course, and for more than eight decades — through prosperity, scandal and loss — that message played out. Harry’s ambition became his son’s, and in 1948 Norman Chandler expanded Times Mirror Square with a 10-story office tower designed by Kaufmann’s protégé, Rowland Crawford. The new addition was to house the staff needed to produce an afternoon tabloid, the Mirror, which folded in 1962.

Some 20 years later, with Norman’s son, Otis Chandler, in charge, Times Mirror Co. — ensconced in its modernist headquarters — had become a media juggernaut with a portfolio of newspapers, magazines, television affiliates and thousands of acres of ranch land in the western United States.

Its annual revenues at their peak exceeded $3.6 billion, supported in part by the rumbling presses in the center of the building that started up each day at 1 p.m. and spun out nearly 1.2 million newspapers Monday through Saturday and 1.5 million on Sundays.

“We didn’t realize how good those days were at the time,” said Shelby Coffey, who served as editor from 1989 to 1997.

More than 5,000 employees marched through the doors, a mix of pressmen and reporters, high school dropouts and Harvard-trained executives, family members, veterans, salesmen and circulation managers, a doctor and a nurse, working three shifts seven days a week.

What it had in professional diversity, it lacked in racial and gender diversity. That would come later.

Behind it all was the noblesse oblige of the Chandlers, who parked their cars — a maroon Rolls-Royce for Norman and Buff, a black Porsche for Otis — beside the Chevys, Fords and Mercurys in the company garage.

Once a week, executives visited each department, and on the 100th anniversary of the paper, recalls George Zambrano, the publisher took all day to congratulate the employees.

“I can’t tell you how much spirit there was at the paper at that time,” said Zambrano, who began working as a custodian in 1963 and retired as a manager of the production department in 1996. “You were holding hands with other people in other departments. We were all a team.”

Employees grew accustomed to such perks as discounted parking, a company-subsidized cafeteria and free dry cleaning if you brushed up against a spot of ink. The test kitchen offered samples of the latest recipe. One publisher built a music room in the basement for staff practices, and celebrity sightings were not uncommon.

Barbara Bush, Vaclav Havel, Ansel Adams, Joan Baez, Madeleine Albright and Richard Nixon were spotted in the lobby and corporate corridors, admiring the collection of modern art that Buff Chandler had helped acquire.

A young politician from Arkansas making a run at the presidency in 1992 stayed for nearly two hours to greet employees.

Rosa Parks, seated in a wheelchair, was presented with a bouquet of roses.

Mikhail Gorbachev, early for his interview with the editorial board, bided his time with a book of cartoons by Paul Conrad.

Muhammad Ali performed his levitation trick for office staff when he stopped by in the late 1990s.

Some dropped by Otis Chandler’s office, which was dominated by two rearing bears — paws above head — that he had shot in Alaska.

Others ate lunch with editors in the executive dining room, made famous by the Picasso lithographs on the walls and a menu by Chef Klaus Kopf. The most VIP were feted in the Norman Chandler Pavilion with its Brazilian rosewood paneling, stone dining table and windows overlooking City Hall.

Like all workplaces, Times Mirror Square had its stories of surprise, near-tragedy and heartbreaking loss.

The so-called Dating Game Killer — Rodney Alcala — worked as a typist in the composing room in the 1970s. A woman pulled a gun in the employment office on the 9th floor and wounded hiring specialist Joseph Glaab, and in 2004, beloved editor and columnist Frank del Olmo died in his office from an aortic aneurysm.

From the outside, Times Mirror Square, all marble wainscoting, limestone cladding and bronze, is stolid and decorous. On the inside, it has an eccentric beauty. Hallways don’t align. Floors unaccountably slope. This messy concatenation of buildings has created an unwieldy labyrinth.

Pneumatic tubes swooshed copy from floor to floor. Computers silenced Linotype machines. The clatter of typewriters became the whisper of word processors. A printing plant two miles away made the basement presses obsolete.

Through earthquakes and riots, The Times has never missed a day of production.

In 1978, demonstrators marched on the building and set fires on the sidewalk to protest the paper’s coverage of the Iranian Revolution, perceived to be sympathetic to the Shah. About 30 were injured in clashes with the police.

“I watched as blood ran from their limbs,” said Elke Corley, who held a number of administrative jobs with The Times from 1967 to 2001. “It seemed unreal to me, as through I was watching a movie.”

A pig was let loose in the Globe Lobby to protest a political cartoon.

A bomb exploded in the Mirror Lobby, punching a hole in the stone wall.

In 1992, rioters in the aftermath of the Rodney King trial verdict hurled rocks into the windows of the building. John Nickols, director of security and safety, was shot at through the glass doors of the Mirror lobby.

With looters working their way through the darkened ground-floor offices, Coffey met them with a pair of scissors, shouting “Get out!” The next day, the National Guard parked tanks on the corner.

Anti-Castro protesters attacked the building after a columnist criticized the administration’s stance against Cuba’s then-president.

As the corporation watched, its Board of Directors simmered over the direction the paper had taken, first under Otis Chandler, then under Tom Johnson, who was named publisher in 1980.

“We were fighting for clean air, for improved traffic conditions,” Johnson said. “We were critical of Southern California Edison building a nuclear reactor at San Onofre. We were for civil rights for minorities.”

But the battles took a toll on him that he would reveal only years later.

“Depression,” he said, “and it was very serious. I would close the door and lie on the floor beneath the desk that had been occupied by Otis.”

When Johnson left in 1990 to eventually head CNN, a recession foreshadowed a darker future.

Employees were told to use the telephone book instead of directory assistance. An outside vendor provided janitorial services. Keys for most company cars were turned in. Plans were put in place to sell Times Mirror Square and move the editorial offices to Bunker Hill and the business offices to Glendale.

In 1995, Mark Willes came on board as CEO, bringing an austerity even to the aesthetics. Saying he wanted to create an environment that better reflected the institution, he removed the art from the corporate dining rooms. Rumors spread that he was offended by the risqué content. In a recent email, he denied that.

After the disclosure of a profit-sharing agreement between The Times and Staples Center, photocopied pictures of Otis Chandler were tacked on the walls of the newsroom with the hope that the paper’s former publisher might return. But the cry was not heard.

When the Chicago-based Tribune Co. offered $6.46 billion for Times Mirror Co., the Board of Directors said yes.

The day after the deal closed in 2000, Stephen Meier, by then vice president of public and government affairs, stepped out of the elevator of the Pereira building and saw that the bronze letters affixed to the marble and bearing the corporate name had been removed. Directional signs with the eagle logo had been taken down.

“It was clear that Times Mirror was not the sheriff in town,” Meier recently said.

Tribune Co. tried to imagine a new future for the building. Dan Forrester, former director of facilities, recalled recently how the new owners considered stripping the Globe Lobby to create a “Today”-like studio.

The company also commissioned artist renderings of a potential shopping mall to be built from 2nd Street into the vast cavern where the presses — by then dismantled and shipped to El Salvador — had once been.

Neither plan penciled out.

After Tribune Co.’s bankruptcy, its Board of Directors created two stand-alone companies. The newspapers lost control of their real estate, leading to The Times and the Chicago Tribune becoming tenants in their own historic buildings.

When recently asked to explain the decision, neither former Tribune Co. Chairman Bruce Karsh nor former Chief Executive Peter Liguori would comment.

After the sale, Onni announced its intention to tear down the Pereira building and an adjacent parking garage and construct two residential towers. Preservationists are fighting that plan.

The Times could have stayed in its historic buildings through the renewal options in the lease agreement, said Onni chief of staff Duncan Wlodarczak, but negotiations with Tronc and its chairman, Michael Ferro, stalled. At the time there was also talk of moving the newsroom to the Westside or into a skyscraper downtown with a helipad.

In the newsroom where photocopies of Otis once hung in protest, reporters now hung placards for the NewsGuild-Communications Workers of America.

Weeks after the staff voted to join the union, Ferro approached Soon-Shiong with an offer to sell The Times and the San Diego Union-Tribune. On Feb. 7, a $500-million deal was reached.

One week later, a production crew finished shooting a film starring Edward James Olmos in the boardroom of the Pereira building.

Times Mirror Square had become popular location, netting $4 million one year, and the rosewood ring table — the Round Table of yore — had become a featured prop in such television shows and movies as “Bones,” “24,” “Get Smart” and “Dreamgirls.”

The Olmos film was a dark comedy called “The Devil Has a Name.” Not long after its wrap, the boardroom table disappeared.

Dismantled and removed from Times Mirror Square, it now resides on the 41st floor of Prudential Plaza in Chicago, said Lynne Allen, director of facilities at the Chicago Tribune.

Camelot had fallen. Ferro had claimed the Round Table for his boardroom.

Twitter: @tcurwen

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.