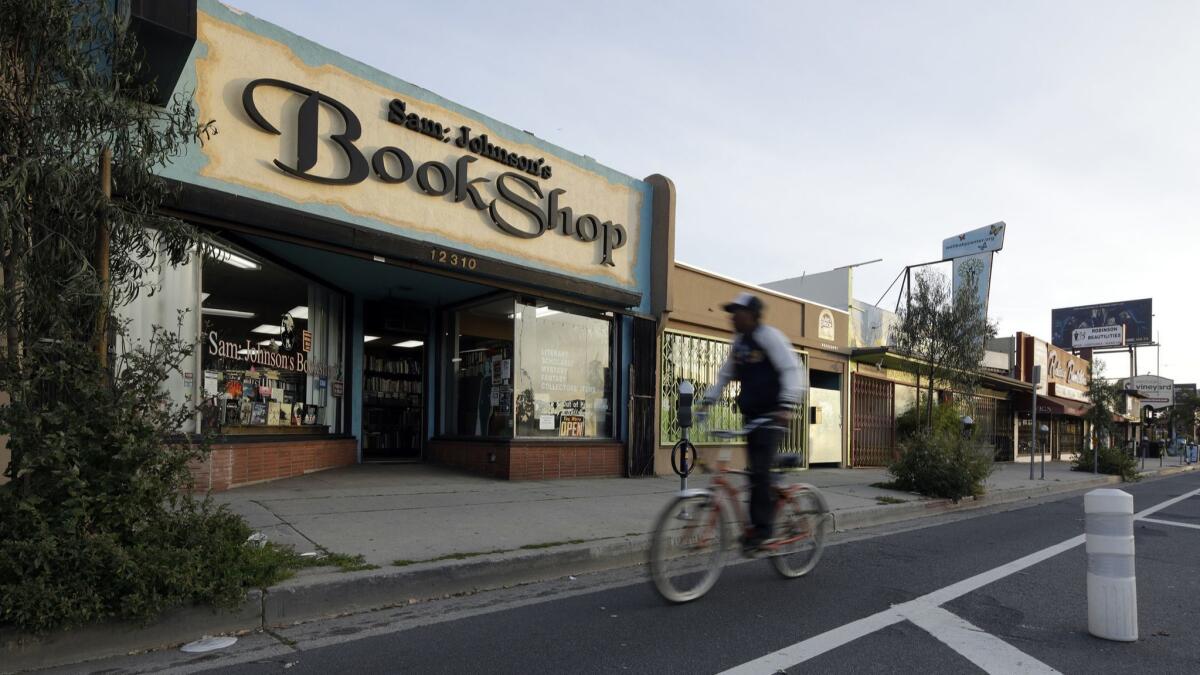

Final chapter for a Mar Vista bookstore — and its unique community

- Share via

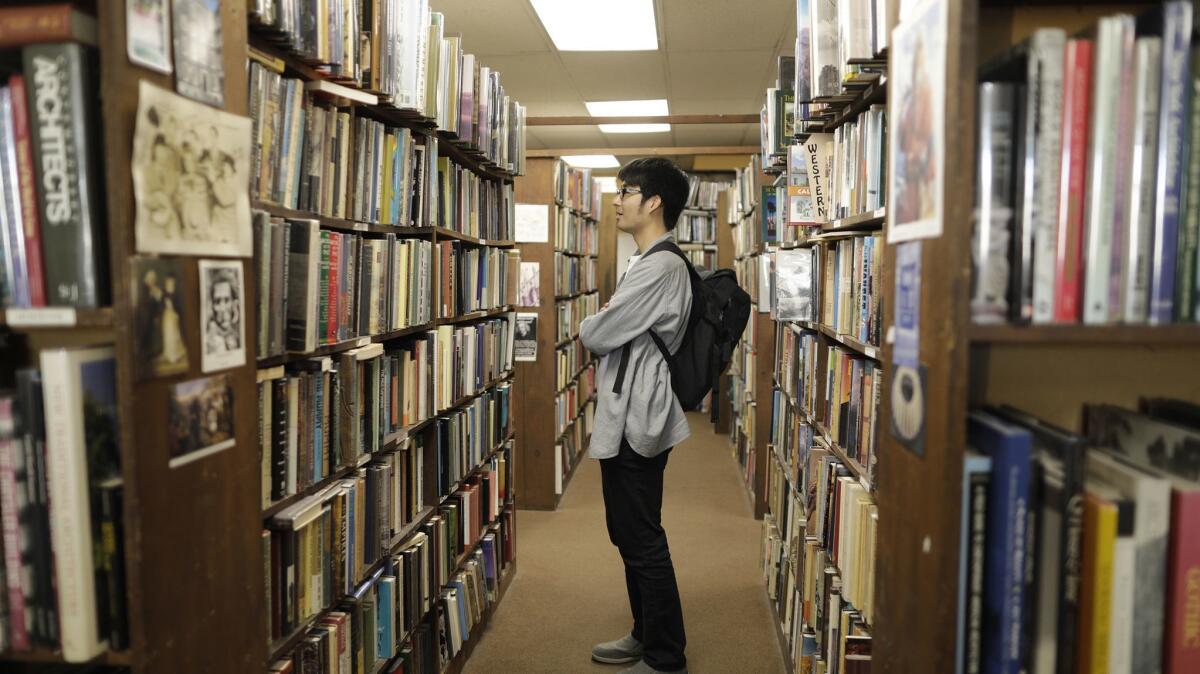

Listen to the rhythm of the stacks. Ghosts. Witches. Vampires. Come this way. Mummies. Mysteries. Mythologies. The words lift like music. True crime is down that aisle. Chaucer and Chesterton are over there. To the left wait Fitzgerald, Hemingway and a smiling Langston Hughes. And calling no attention to himself is Dostoevsky, so dark, yet so pure in the way he understood the things that menace the soul.

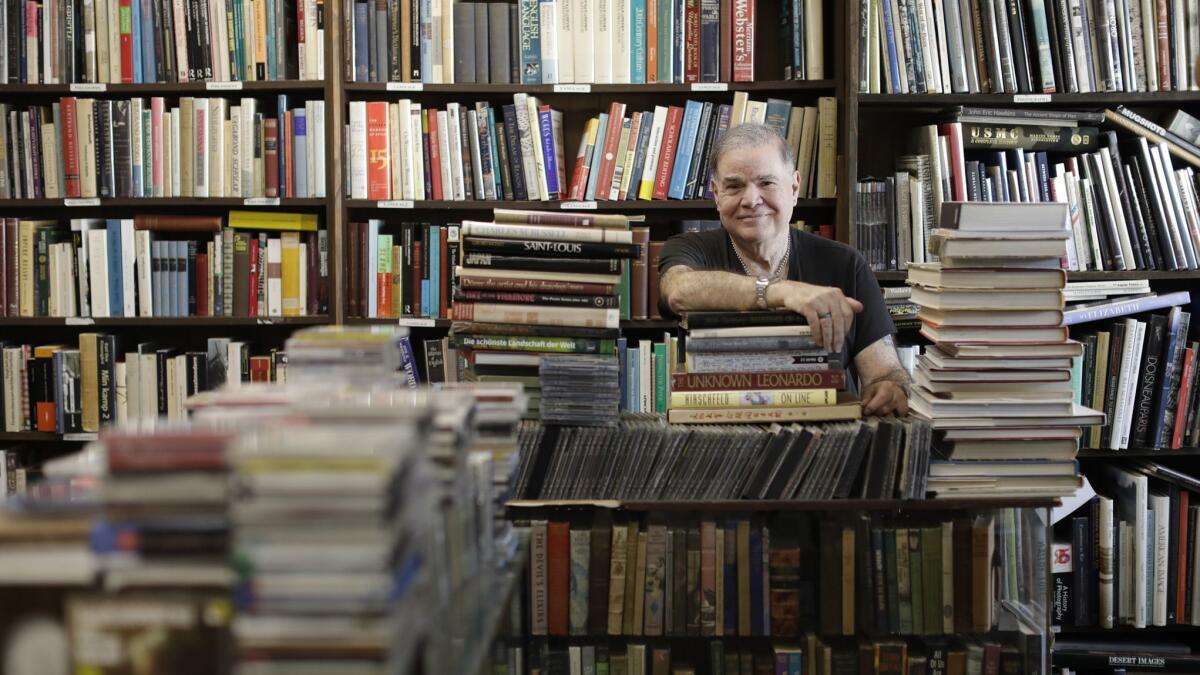

David Benesty knows the bindings, spines and pages of them all.

The manager of Sam: Johnson’s Bookshop in Mar Vista, he roams amid titles in black shorts, T-shirt and pork pie hat. With a discerning gaze and a cantor’s voice, he quotes W. Somerset Maugham and professes his love — “they are my popcorn reads” — for Dr. Fu Manchu adventures by Sax Rohmer. The world is in these rows, in poetry and prose, in the writings of James Boswell, in the celestial flare of sci-fi covers.

“Big sellers,” says Benesty, holding up an Isaac Asimov novel. “Very collectible.”

But Ecclesiastes whispers from another shelf that everything has its season. Things change. Buildings get sold. Rents trend skyward. Don’t even mention Amazon and the shrinking attention spans of the young. Benesty, whose last name is known to some as Ben-Veniste, has been selling rare and used books here for decades, but the owner has put the building on the market and the shop is set to close by the end of May.

When a piece of a community succumbs to the weight of change, irreplaceable characters and singular moments that drifted through and defined the lives of countless Angelenos vanish against the desires and fascinations of new times. It is a curious and cruel evolution. Storefronts and painted signs grow faint against screens and smartphones that tug us away from a communion of voices meeting by happenstance to chat about politics, film or the latest bestseller.

The shuttering of a bookstore is like a recurring couplet — Caravan Book Store in downtown Los Angeles closed last year; Circus of Books in West Hollywood, in February — but each has its own peculiarities and enchantments, its floods and fires, water stains and worm holes, and the occasional first edition from a past century, still crisp to the touch.

“That tradition is gone,” says Benesty, 79, keys dangling from a belt loop. “People have Kindles, if they read at all. You know, I had a young man come in who had never read a book. He had been through college. Cliff notes. He wanted me to recommend something, so I went with the obvious, ‘Of Mice and Men.’ He came back, and I gave him ‘The Sun Also Rises.’ He discovered he loves to read.”

It is late morning, and the air is cool on Venice Boulevard. Benesty stares out the window. Voices of children at the preschool next door pierce and fade. The tattoo artist down the street is blaring heavy metal, the barber shop on the corner is open, and a few doors down, Alberto Hernandez, who makes hats for celebrities, is bent over a vintage sewing machine. A boy whistles. Lovers pass. Lives like novels, here and there, gathering in tiny splendors.

Hernandez knows well the Darwinian map of gentrification, commerce, parking battles and changing lifestyles that are altering the geography and spirit of neighborhoods across the city. Sitting amid threads, pins and brims, Hernandez, who emigrated from Mexico more than a decade ago, found refuge on the block after soaring rents forced his shop out of Venice.

“I was on Abbot Kinney in Venice for five years,” says Hernandez, his voice as quick as a bobbin. “It was insane because GQ magazine came in and wrote a story that the street was cool and had a vibe. You could see Bob Dylan buy a sandwich. My rent went from $1,050 to $10,000. I moved to a place around Glendon and Venice, and in two years, my rent went from $3,500 to $6,000. I came here in 2018. Rent is $3,500.”

One man’s refuge is another’s untenable ground. The Venice Grind coffee shop near the bookstore closed last year. Pepy’s Galley, a diner in a bowling alley across the street, disappeared years before. Timewarp Music, which sells guitars and speakers, is facing as much as a 40% increase in its rent or the prospect of moving. The rent at Sam: Johnson’s Bookshop jumped from $3,500 to $4,000 this year, high for a store that on a recent Thursday sold $18.95 worth of books. The shop on some months barely clears $200 after expenses.

Benesty turns from the window and looks over the stacks. The radio plays low. The door opens. Steve Goldman, poet, iconoclast and one-time construction worker, strolls in, takes off his jacket, and eyes Benesty. They appear to resume an unfinished conversation from another day.

“You’re the pope of parsimonious praise,” says Goldman.

“I like what I like,” says Benesty.

“Mmmmm.”

Sam: Johnson’s Bookshop — named for the 18th century writer and moralist who published “A Dictionary of the English Language” — was founded in Westwood in 1977 by Larry Myers and Bob Klein. “After three years,” a store history reads, “[the] landlord amused himself by tripling our rent.”

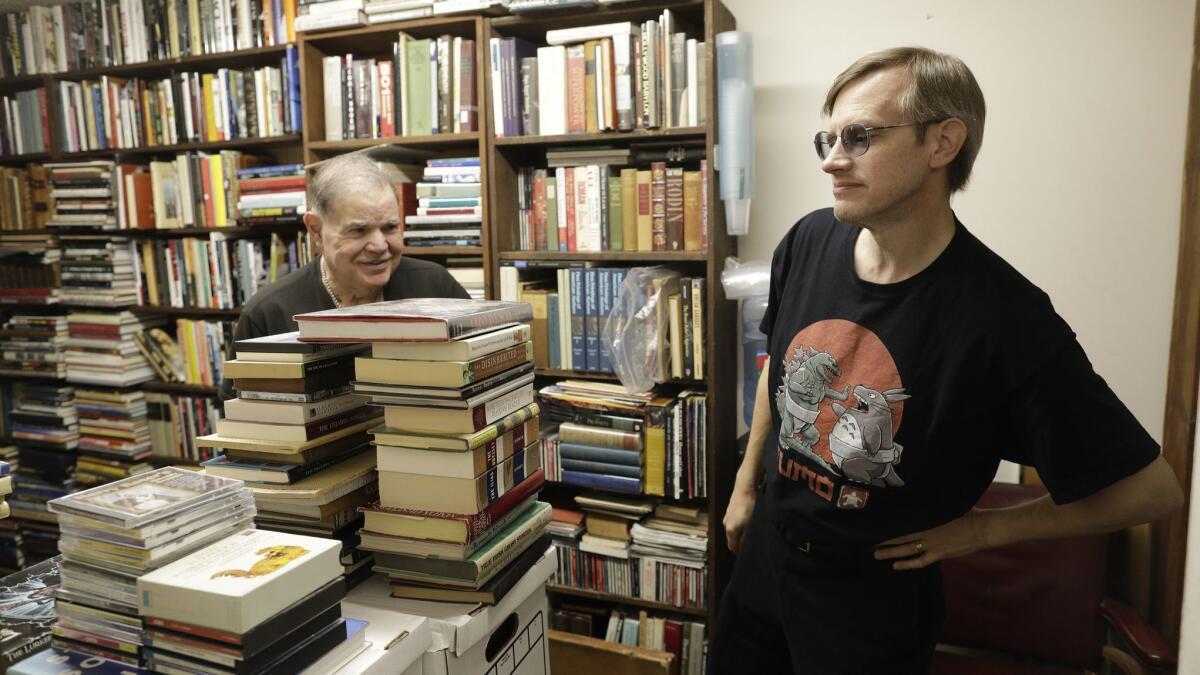

The store moved to Santa Monica Boulevard, but in 1987, to again escape escalating rent, relocated to Mar Vista in a space that was once a branch of the Los Angeles Public Library. Klein died in 2016 and Myers has taken ill. Benesty, a first generation Turk whose family hails from Istanbul, runs the place.

“I was supposed to be here two weeks, but that was 30 years ago,” says Benesty, stepping into a side room filled with boxes and coffee mugs. “The first Sunday I was here, we made over $600.”

He sits and travels back to those times when impressions were made by eccentrics who now linger only in anthologies tucked in the mind. “There was Red over at Baroque Books in Hollywood. He’s long gone. He was a great bookman, a wonderful curmudgeon. Harry Bierman over at Pik-a-Book was a grandmaster at bridge, but he knew his books.”

The word “bookman” rings out lovely and curt.

It resonates, like “blacksmith” or “butcher.”

Benesty can do that to syllables. His voice is deep, clear and polished. He knows its power, the subtle way it coaxes and convinces, how its inflections snap and drift like echoes at dusk. His eyes quick and searching, he seems like a character out of Edith Wharton or “The Great Gatsby.” He says things like: “He’s a charming, charming man” or “I am not fond of Dickens’ anti-Semitism” or “My father was a florist for 40 years, and my mother was allergic to flowers.”

His father left Turkey to avoid military service and ended up in New York as a singing waiter before opening a flower shop in Los Angeles. Benesty, who grew up around Lafayette Park, discovered his voice as a boy when he was paid $10 to sing “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” in a concert. He sang for film composers Franz Waxman and Bernard Herrmann. He appeared in a choir on the “Loretta Young Show” in 1954. During his years in the Army in the early 1960s, “all I did was sing. The sergeants never messed with me. The general and their wives loved me.”

Benesty performed in the Seattle and Santa Monica operas. He can still recite a line from a review of his performance as Schaunard in “La Boheme.” (It mentions footlights and projection and a young man’s promise.) A voice teacher and cantor for 50 years, Benesty has officiated at more than 2,000 bar and bat mitzvahs and has sung at synagogues including Temple Israel of Hollywood.

Books found him early. He went from “The Tin Woodman of Oz” to Dostoevsky, Pushkin, and to more recent authors including Umberto Eco, Margaret Atwood, Bernard Malamud, Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Bret Easton Ellis. He calls their works the new classics and is proud of the display he’s arranged for them. He notes, “We have the best medieval section of anyone” and, nodding toward a shelf, adds, “That one’s scarce, ‘Ten Operatic Masterpieces.’ ”

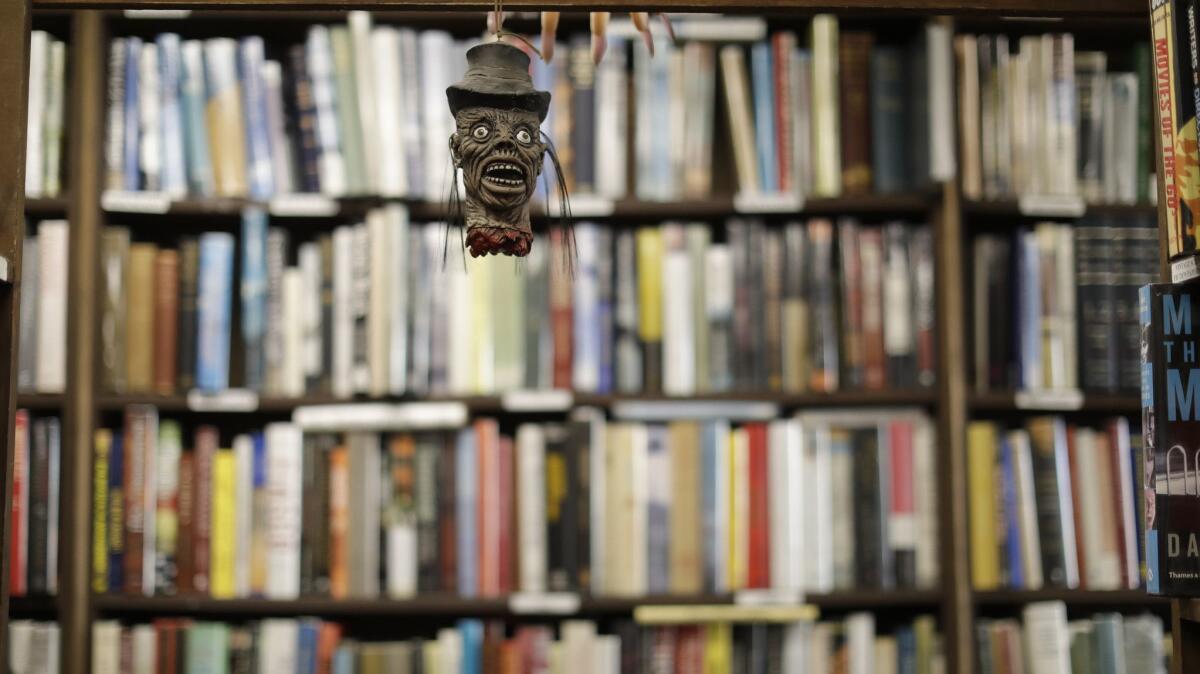

The coffee is on; the crew in place. Margaret Hosier, a volunteer clerk, is unboxing books. Assistant manager Michael Stearnes is busy behind the computer next to a grandfather clock that is shadowed by the figurine of a witch. Many such creatures — gargoyles and zombies too — peek out from shelves, giving the store the air of an unending Halloween or a trip into an old curiosity shop, where the sage in the pork pie hat peruses stacks of books that lean and teeter like the scattered columns of ancient ruins.

A man appears from the biography section.

“Hello,” says Barry Ghabaei, brisk and inquisitive, and dressed in jeans and white button-down. His self-published books, including a story collection titled “Faith,” are on sale at the counter. “David and I talk literature. E.M. Forster is one of our favorites. Hemingway. Henry James. Raymond Chandler. It really juices our days.”

Ghabaei pivots and meanders down an aisle. Two women arrive and inquire about cookbooks. They seem pleasant enough, but one wonders about the sign they’ve spotted that reads: “Keep in mind that extended browsing without purchasing is really more for libraries! There’s a library down the street.” Hosier wasn’t sure if Benesty should have put the sign up. Some customers have complained that David is rude and the warning could send the wrong message — but, as he often says, “a book lover cradles a book, a browser flings open covers.”

Someone, after all, has to take a stand in the war against civility: “Thousands of dollars worth of books,” he says, “have been ruined by people who dropped them and broke their spines.”

Goldman, glasses dangling from a string over a pin-striped vest, steps close to Benesty and whispers: “Hey, David, there’s a lady out here who wants to sell some books.” Benesty walks toward her. The woman is offering biographies on Mary Queen of Scots, which her grandmother, before she died, had thought about developing into a screenplay. Benesty declines. The woman walks away. Goldman turns and clears his throat. He is angry that the store is for sale.

The bookshop’s closing, he says, will be part of “the desecration of culture in favor of some kind of addictive madness for money…. Bookstores are the Agora of ancient Greece. This is a critical thing for our society. There, I’ve said it. I said my peace.” He hands a visitor the ode he wrote to Pepy’s Galley, which, when it closed in 2014, he called “the essence, the heart of Mar Vista, the marketplace of ideas and communion.”

That sense of loss is happening again. The only thing sacred is change, and that’s a hard thing for an old man to endure. After that there is memory. Silence. And the words on pages you carry with you, the ones read when you were young, the phrases that still find their mark: “April is the cruelest month” or “There are some things which cannot be learned quickly and time, which is all we have, must be paid heavily for their acquiring.”

Countless words have passed through Benesty’s hands, slid across his eyes. Even his skin has been turned into a page. The line of a Psalm is tattooed on his arm. “Out of the depths have I cried unto thee O Lord. Hear my voice.” His aunt and cousins were murdered at Auschwitz. A red star is stamped further up the arm. “It’s for the slaughter of the innocent,” he says, “I didn’t want the star to be beautiful. I wanted it to be crude.”

Hosier has unboxed the books. She is finished for the day. The poet is gone, Ghabaei too. Late morning slips into afternoon, and one wonders about Proust and all the sorrows and sublime encounters that make a life. Benesty is devoted to the bookshop, but it doesn’t define him. He has his voice lessons, his students. But he pauses for a moment to consider: No more store to open. No more shelves to stock. No more irreverent browsers to chide. (“I never yell. It’s not good for the voice.”) No more bringing fresh cut flowers every Thursday.

Yes, he concedes, it will sting.

“In the end, though, the community didn’t really support us,” he says. “People would come in to browse and say what a good bookshop it is. But they’d leave without buying a book.”

Benesty may travel to Buenos Aires for a while. He’s been going for years now. Someone told him long ago that a man can find himself in Buenos Aires, the way Larry Darrell traveled through India searching for transcendence in Maugham’s “A Razor’s Edge.”

“Have you found yourself?” a visitor asks.

“I’ve found part of me,” he says.

He pats the phone riding on his hip.

“I’ll do a lot of reading,” he says, “I have 900 books on here.”

The air stills. He smiles. The world is splendid in its ironies.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.