New storm water runoff rules could cost cities billions

Cities in Los Angeles County face spending billions of dollars to clean up the dirty urban runoff that washes pollution into drains and coastal waters under storm water regulations approved Thursday night by the regional water board.

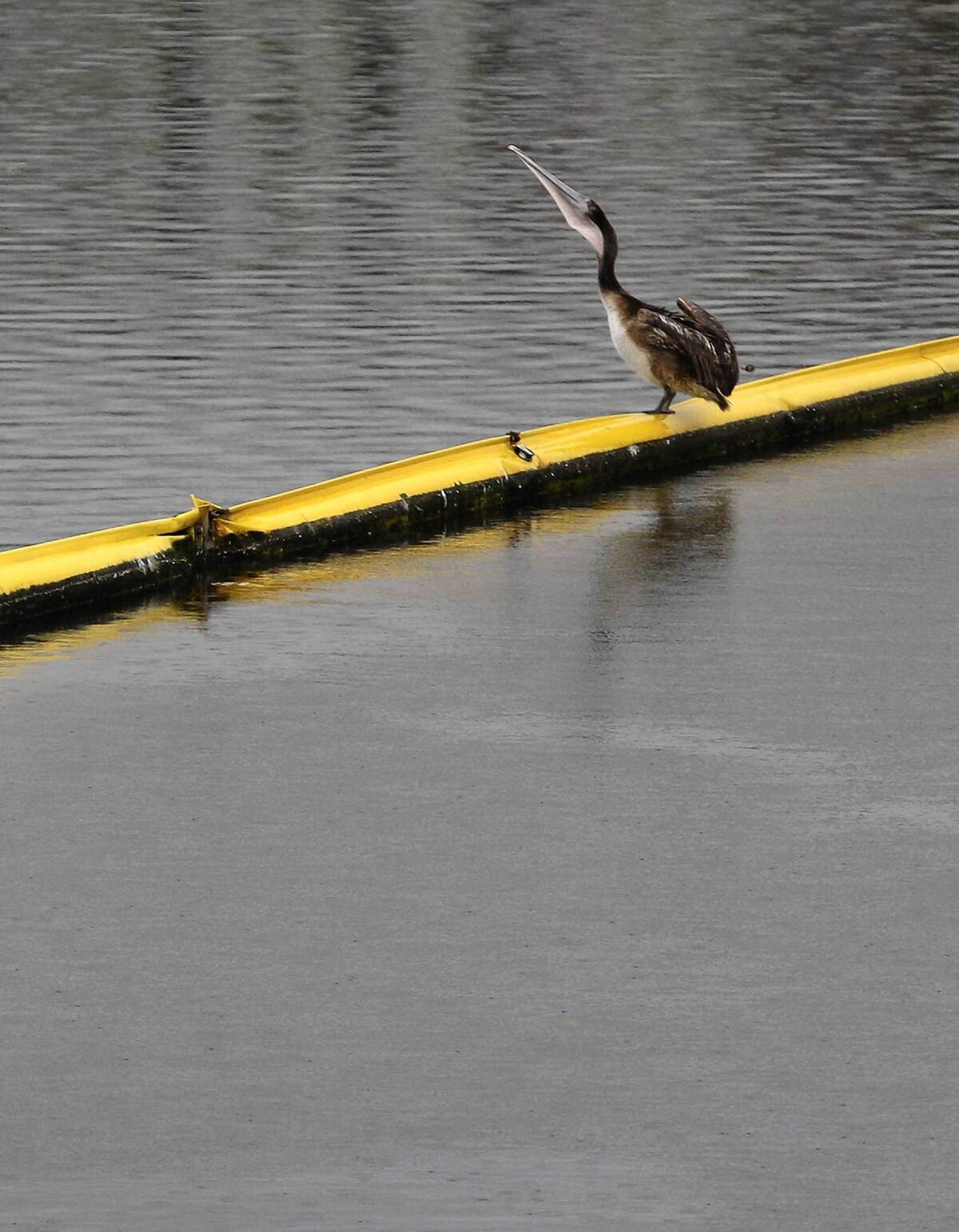

Despite more than two decades of regulation, runoff remains the leading cause of water pollution in Southern California, prompting beach closures and bans on eating fish caught in Santa Monica Bay.

The runoff — whether from heavy winter rains or sprinkler water spilling down the gutter — is tainted by a host of contaminants from thousands of different places: bacteria from pet waste, copper from auto brake pads, toxics from industrial areas, pesticides and fertilizer from lawns.

“Municipal wastewater treatment has made incredible strides over the past 20 or 30 years, and other sources of pollution have been well controlled,” said John Kemmerer, regional associate water director for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which oversees the Clean Water Act. “It really comes down now to urban runoff.”

The regulations, which the Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Control Board adopted after a daylong hearing, place limits on 33 pollutants ranging from coliform bacteria to hydrocarbons and lead.

“This is the only way to move forward,” said board member Madelyn Glickfeld.

Environmental groups countered that the regulations contain provisions that weaken enforcement.

“We’re extremely disappointed with this decision,” said Kirsten James, water quality director for Heal the Bay. “At the end of the day [the cities] don’t have that stick waiting for them. That’s very disconcerting.”

The requirements, in the form of a pollution permit, are an overdue renewal of storm water regulations adopted in 2001 that failed to reap hoped-for improvements in water quality.

The permit applies to most cities in the county as well as the county flood control district and unincorporated areas.

Over the last few years, other regions in the state have adopted similar storm water regulations. But none address as many pollutants as the Los Angeles rules, which cover 3,000 square miles containing about 500 miles of open drainage channels and 3,500 miles of subterranean drains.

The Los Angeles provision seeks to reduce storm water flows to the ocean in ways that would replenish aquifers, thus boosting local water supplies.

Municipal officials say they will pursue a variety of tactics to meet the regulations, ranging from better street sweeping to collaborating on the construction of large infiltration basins that will capture storm water and let it seep into the ground to recharge groundwater.

They also plan to adopt low-impact development ordinances similar to one approved in the city of Los Angeles that require new, larger construction projects to use parking lot and landscape designs that would retain a certain amount of runoff on site.

Building “green infrastructure” to capture the runoff is more cost-efficient than trying to treat it at thousands of small sources, Kemmerer said.

Parking lots at public buildings such as schools could be converted to permeable paving.

Street curbs could be altered to send road runoff to plant beds rather than storm drains. Small pocket parks could be created with plantings to hold and filter rainwater.

“This takes a different approach” that gives cities flexibility to meet the pollution standards “in the most economical way possible,” said Charles Stringer, the board’s vice chairman.

The cost of complying with regulations has been a top concern for cities — although environmentalists say municipalities are exaggerating the expense.

Shahram Kharaghani, watershed protection division manager for Los Angeles, estimated it will cost $5 billion to $8 billion to meet the storm water standards for the city over the next two decades.

But the projects won’t just improve water quality, he said, they will recharge groundwater supplies, create wildlife habitat and create green jobs.

“This is no longer put the water in the pipe and get it out to the ocean,” he said.

The county flood control district is preparing a ballot proposal for next year that would impose a parcel fee to pay for the runoff controls.

At $54 for an average residential parcel, the fee would raise about $275 million a year, Kharaghani said.

But what the cities view as needed flexibility, environmental groups describe as offramps that will let municipalities off the compliance hook.

“It is going to be the public that suffers, the water quality that suffers,” warned Noah Garrison, an attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Environmentalists objected in particular to a provision they interpret as saying that if municipalities adopt a watershed plan approved by the board and implement it, they will be considered in compliance, even if the pollution limits are exceeded.

The water board staff, which has worked for several years on the new regulations, rebutted that contention, saying the requirements were much more stringent than earlier permits.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.