California’s jails are so bad some inmates beg to go to prison instead

- Share via

Reporting from SACRAMENTO — Ever since he stole his first car at age 10, Cody Garland has spent much of his life behind bars. Now 35, he has served time at eight different California prisons.

But the hardest stint, he says, was not in a state penitentiary. It was in a Sacramento County jail, where in 2016 he was sentenced to serve eight years for burglary, identity theft and other charges.

Medical care at the jail was even worse than in prison; untreated glaucoma left him legally blind, he says.

Solitary confinement — in a windowless room — was a common punishment; Garland says he lost track of whether it was day or night during a spell in solitary and began to hear voices.

Mental-health help was hard to get, he alleged, even after he started swallowing shards of metal and tried to hang himself. He detailed the treatment in a lawsuit accusing the county of subjecting inmates to inhumane conditions — a claim the county denies.

“I’ve done a lot of prison time,” he says, “and this was the worst time I’d ever done.”

Garland is one of more than 175,000 people sentenced to county jails instead of state prisons in the last eight years because of sweeping changes to California’s justice system, according to an analysis of state data by The Marshall Project. The reforms were intended to ease prison overcrowding — and they have.

But the changes were also supposed to help people convicted of nonviolent crimes, by letting them serve their sentences close to home in county jails with lots of education and training programs.

It hasn’t worked out that way in some urban counties. Jails built to hold people for days or weeks — awaiting trial or serving short sentences for petty crimes — have strained to handle long-term inmates, many with chronic medical and mental-health problems and histories of violence.

Statewide, assaults on jailers increased almost 90% from 2010, the year before prison downsizing began, to 2017, the most recent year for which there is complete data. Mental-health cases, which had been declining in jails, have risen. County spending on medicine for inmates has jumped (to almost $64 million in 2017 from $38 million in 2010), and the cost of psychotropic medication has recently surged. Legal challenges over inmate treatment have expanded to about a dozen county lockups.

Deaths in California jails jumped by 26% in the years after they started receiving long-term inmates, peaking at 153 in 2014 before falling to 133 in 2017. That year, California had 17.7 deaths per 10,000 inmates; Texas, which has the second largest jail population, had 13.2.

Problems have been particularly acute in counties with old facilities, tight budgets and a lot of long-term inmates, including Sacramento, San Bernardino, Fresno and San Diego, which had a spate of suicides this spring. Los Angeles County has had to deal with the largest number of these inmates: 45,000, or about a quarter of the total since 2010.

For these counties, California’s prison changes have been “a budget buster,” said Mike Brady, a former official with the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation who now works as a consultant. The jails now “have serious mental illnesses, violence. They’ve got gang issues. They’ve got developmental disabilities. They’ve got physical disabilities. They’ve got to change their whole physical plant. It’s a phenomenal expense.”

California’s experiment in prison downsizing has implications for states across the country as they try to cut the size of their prison systems. Some, like Texas, are tackling the issue because of the high cost of locking people up, while others, like Alabama, are under pressure to relieve overcrowding and violence. And in many regions, voters are concluding that prison populations, which include disproportionate numbers of people of color, reflect outdated “tough-on-crime” policies.

For such states, “California is a pretty remarkable study,” says James Austin, a corrections expert who has examined California prisons and jails. “The whole system has dropped about 220,000 people” without the surge in crime many critics feared.

Some counties have coped well with the changes. In wealthy Silicon Valley, governments have poured cash into fixing up their jails. They have also spent a lot on programs to keep people out of jail in the first place, and to help those who are incarcerated make a successful return to their communities.

Others, such as Humboldt County, a rural area along the rugged coastline about 300 miles north of San Francisco, say they have relatively few long-term inmates because judges and prosecutors have changed their sentencing practices to allow people to serve more of their time in the community.

“One of the things that made us successful is we’ve been fortunate not to have some of the longer sentences that some other counties have had,” said Capt. Duane Christian, who leads the Humboldt County Correctional Facility.

Overall, the consequences for county jails aren’t easy to measure. No state agency collects data that could answer important questions, such as what percentage of a county’s inmates are there because of the new measures and whether some jails hold an outsized number of inmates with long sentences.

The state does track the size of the overall jail population, which increased briefly after a 2011 U.S. Supreme Court decision required California to downsize the prisons, climbing to an average of 82,000 people in 2013. But the number of people in county lockups began to drop after 2014, when state voters approved a measure to cut the length of some sentences. Last year, county jails held 72,500 people.

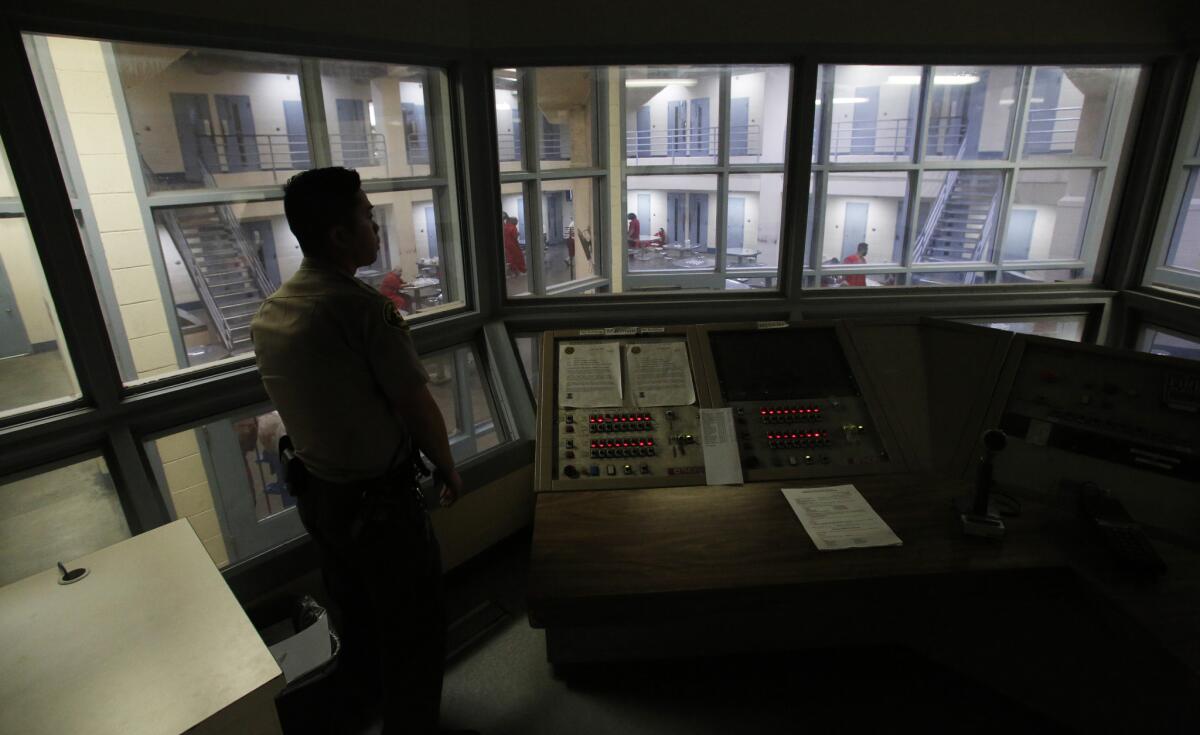

L.A. County still holds a lot of long-term inmates — almost 2,700 on average, as of the third quarter of 2018. That might not seem like a huge number in a giant jail system that generally housed about 16,500 people last year.

But like other counties, L.A. says it is having problems associated with this different population. The number of mental-health cases L.A. jails are reporting to the state has doubled since 2010, to 24,400 last year. And reported assaults on guards and other jail workers are double what they were before prison downsizing, at about 550 per year, though critics have questioned both the validity of the data and the county’s assertion that violence is rising in its jails.

The state allocated $440 million to Los Angeles in the last fiscal year to offset the costs of the new measures, including staffing, treatment programs and court hearings for people who violate the terms of their community-based sentences.

Sacramento County, for one, continues to struggle with adapting local jails to house long-term inmates.

The county has about 1.5 million residents and has received about 8,000 long-term inmates since 2011, according to the Marshall Project’s analysis. The data do not show how many of those people are still in the county’s jails, which generally house 3,500 to 4,000 people.

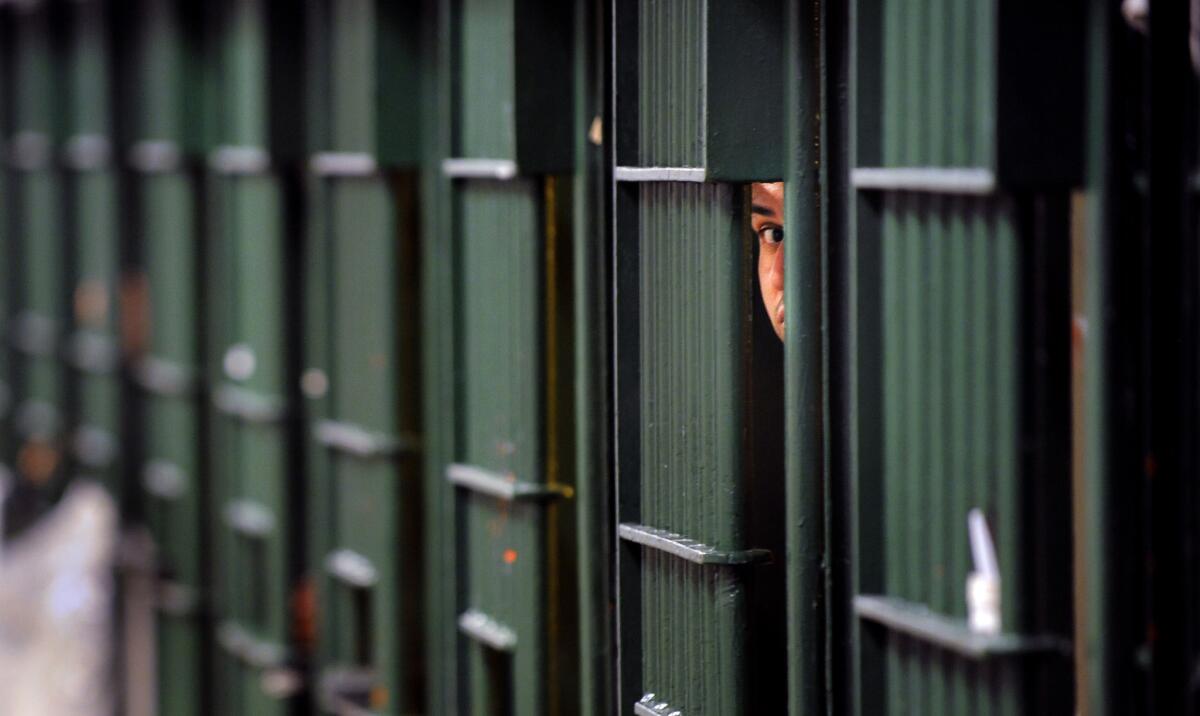

Most people waiting for trial are housed in the Sacramento County Main Jail, a series of six slender concrete towers a few blocks from the Capitol downtown. Built in 1989, the jail can hold up to 2,380 people.

RELATED: Wrongfully convicted in California? To get compensated, you must prove your innocence »

The county’s other jail, the Rio Cosumnes Correctional Center, sprawls across a 140-acre campus south of the city and can hold 1,625 people in buildings and dorms, some of which date to the late 1950s. It’s here that Garland tried to end his life.

The number of Sacramento inmates with psychological problems has soared. Last year, its jails reported about 8,800 new mental-health cases, up from around 4,100 in 2010 before the prison reform efforts took hold.

Violence at the jails has also increased. While the county does not report how often inmates attack one another, assaults on staff have almost doubled, to 111 last year from 58 in 2010.

“One of the things that we’ve gotten from this is a more sophisticated offender — people that have done prior prison sentences,” said Lt. Brad Rose of the county Sheriff’s Department, which runs the jails. “It’s the state prison mentality and sophistication. They make weapons out of anything.”

On the positive side, he said, the county has used state funding to increase the programs it offers inmates to help them prepare to return to their communities.

Sacramento County receives millions of dollars from the state each year to help offset the costs of the new measures, money which covers drug court, public defenders and prosecutors as well as jails. In 2018-19, those payments amounted to $320 million, according to the county budget.

Those funds are not enough to pay for fixes to the jail or the additional staff needed, county officials contend. They declined to provide specifics, citing pending litigation.

In August 2015, the nonprofit Disability Rights California published a scathing report about Sacramento jail conditions. The group found the county held disabled inmates in excessive solitary confinement and provided inadequate mental health care; in one unit, inmates spent nearly 24 hours a day in bare cells, released only once or twice a week into a dayroom that smelled of feces.

The group, together with the Prison Law Office, which has successfully sued the state prison system over the treatment of inmates, threatened to file a suit against Sacramento. In January 2016, the county began to negotiate and hired some experts of its own to evaluate its jails.

Their findings were bleak:

- They confirmed that the main jail put people in solitary confinement for 23½ hours a day, in conditions that were “very stark and unlikely to meet constitutional standards,” and found the jails’ use of segregation “dramatically out of step” with emerging national standards on the dangers of solitary confinement for mentally ill prisoners.

- The medical screening process was “wholly inadequate” to identify inmates with disabilities, and inmates deemed suicide risks spent weeks locked alone in empty classrooms without toilets.

- The number of staff members in both county jails was “startlingly and dangerously low,” leaving them to “operate in a state of near perpetual emergency.”

In settlement negotiations, Disability Rights asked that inmates be given more time out of their cells, more services for the nearly 40% with mental illnesses and better medical care for those serving longer sentences under the new measures.

After 2½ years, negotiations broke down.

In July 2018, Garland and five other inmates sued Sacramento County, accusing it of housing about 3,800 people in “overcrowded and understaffed jails,” subjecting people to “dangerous, inhumane and degrading conditions.”

The county denied providing inhumane treatment or inadequate care but did not address specific claims by Garland or the other inmates.

Other counties, such as Santa Clara, have reached settlements in similar suits. But Sacramento officials said the plaintiffs’ proposal would cost too much and happen too fast. The plan would require an additional $50 million a year to operate the jails, they said, and $160 million for renovation. To cover these costs, the county said, it would have to gut programs for community mental health and homelessness.

“It is unfortunate that once again California county governments are being asked to solve the state’s correctional issues,” said a statement issued last summer by Susan Peters, a county supervisor. She called on the state to “provide the full funding necessary to responsibly shift the state’s prison population to county jails.”

The Sheriff’s Department had been making improvements to the jails even before the lawsuit was filed, said county spokeswoman Kim Nava. She said the county added 72 new positions for jail staff in the last year, including 12 health workers, and increased its contract for psychiatric services. In March 2017, the county built a 20-bed mental-health unit at the Main Jail.

The lawsuit is before a federal judge in Sacramento. The county and the plaintiffs’ lawyers are in settlement talks.

Garland no longer spends his days in the Sacramento jail. Since December, he has been living in a prison medical facility in San Luis Obispo, where he says his health problems have improved.

How did he get transferred? In 2018, he hit a sheriff’s deputy in the jail. Garland did not contest charges of resisting an officer and assault likely to produce great bodily injury, a felony.

He begged his public defender to make sure that this time, he went to prison.

“They wanted to give me six months in jail,” he recalled recently. “I said I’d take two years if you’d just let me go to prison.”

This article was published in partnership with The Marshall Project, a nonprofit newsroom that reports on the criminal justice system. Sign up for their newsletter, or follow the Marshall Project on Facebook or Twitter. The Marshall Project receives funding from the California Endowment and other organizations that favor efforts to reform California’s criminal justice system. Under terms of its funding, The Marshall Project has sole editorial control of its news reporting.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.