The pressure is on for Jackie Lacey, L.A.’s first black district attorney, after high-profile police killings

- Share via

“You help killer cops, you help killer cops!”

As the chant rumbled through a packed community center in South L.A. recently, Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey stared at the people pointing their fingers at her. “You’re a race traitor,” one woman screamed. “A betrayal, an accomplice to murder.”

When she finally addressed the crowd members at a town hall meeting on race and the criminal justice system, Lacey told them she understood their anger. A little boy screamed at her from the front row, “No, you don’t!” Her shoulders slumped and Lacey asked them to give her a chance. They booed and demanded her resignation.

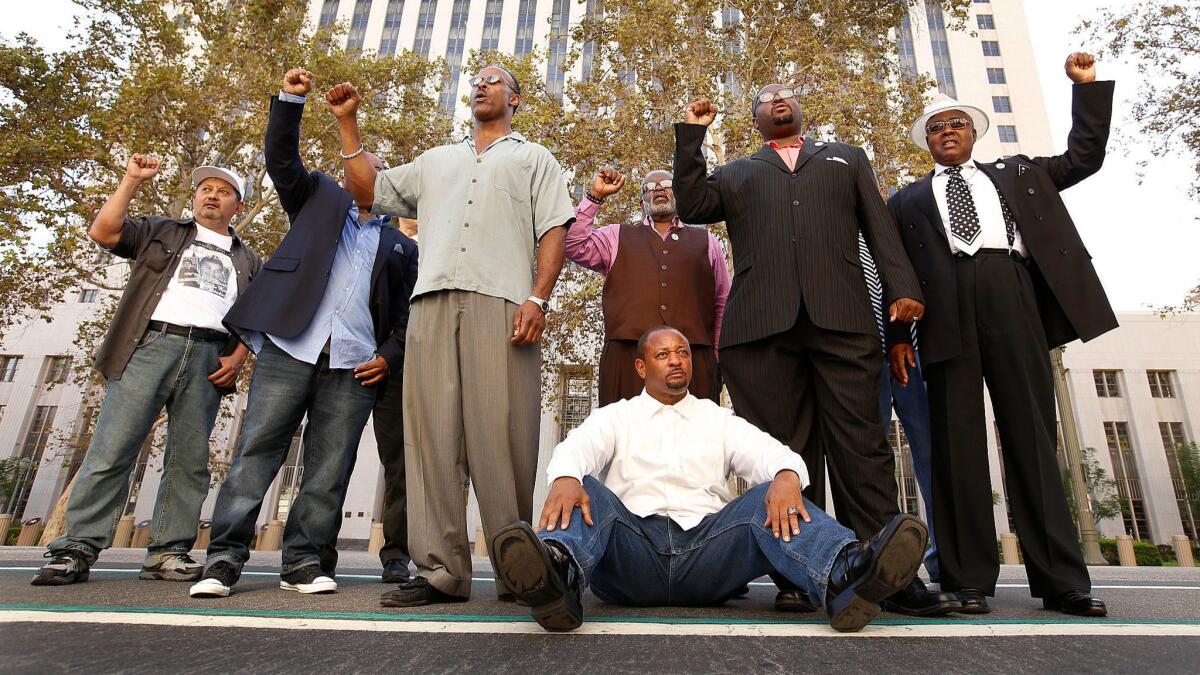

The recent event illustrated the intense pressure on Lacey — the county’s first black district attorney — to take a tougher stance in prosecuting police officers who use force against civilians, particularly African Americans.

In her latest test, Lacey has to decide whether to file charges in two high-profile killings of black men by police, including one in which Los Angeles Police Department Chief Charlie Beck has publicly urged her to prosecute the officer who shot an unarmed man in the back near the Venice boardwalk last year.

The decisions, and the larger issue of how prosecutors deal with police force, weigh heavily on the otherwise popular Lacey, who this year became the county’s first district attorney to win reelection without a challenger in 60 years.

Her office has not filed charges against an officer in an on-duty shooting in more than 15 years, long before she took the helm. But Lacey has drawn especially forceful criticism from some African American activists who say they feel she has failed them.

For her part, Lacey says she has a deep-rooted respect for police but also a clear view of their historical abuse of black people and how that influence carries into the present. After police shootings, she said her mind often jumps to the same question: Was it racially motivated?

“Who could not think about that?” she said in an interview, adding that she always looks for assumptions in cases, especially those involving people of color. She recently announced new mandatory training for prosecutors in how to avoid implicit racial biases.

Some civil rights advocates say it’s unfair to blame Lacey, individually, for a system that trains prosecutors to view law enforcement as the good guys and then expects them to look at officers as potential suspects in force cases.

“The culture of the D.A.’s office is to circle the wagons around cops who you need to make your cases. That’s human nature,” said longtime civil rights attorney Connie Rice, adding that she believes Lacey is one of the fairest prosecutors she’s met.

Beyond that, Rice said, officers have wide latitude under the law in use-of-force encounters. Officers can’t be held criminally liable if they acted reasonably and genuinely feared for their safety when they fired their weapons — an extremely tough thing for prosecutors to disprove.

Some of Lacey’s critics have contrasted her inaction to the decisiveness of Marilyn J. Mosby, Maryland’s state attorney for Baltimore. Mosby moved quickly to file criminal charges against six officers just two weeks after Freddie Gray, a young black man, suffered a fatal spinal injury while in police custody. But all of the officers were acquitted or had their charges dropped.

Councilman Marqueece Harris-Dawson — whose South L.A. district is considered the heart of the city’s black community — said he’s never heard any complaints about Lacey. The real problem, he said, is shootings by officers are investigated by their own departments.

“It is the equivalent of the police stopping me and saying, ‘Let me see your license,’ and me saying ‘No, but I have it. Trust me,’” Harris-Dawson said.

But Dermot Givens, a political consultant and defense attorney, said Lacey deserves criticism. Givens said some of the city’s African American residents feel betrayed by her decisions not to file charges against officers in controversial cases. Almost worse, he said, is her sluggishness in announcing whether she’ll file charges. The delays, Givens said, can only be explained as “damage control.”

“Jackie Lacey is just quiet — silent — and hopes it all blows over,” Givens said. “That’s terrible, absolutely terrible, for an elected official….The buck stops with her.”

Lacey came to power in 2012, shortly before the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, which rekindled a national debate over race and policing.

Last year, civil rights activists lambasted her for not prosecuting Daniel Andrew, a white California Highway Patrol officer seen on video repeatedly punching a mentally ill black woman on the 10 Freeway. Lacey’s office concluded the officer was required to use some level of force to keep Marlene Pinnock out of freeway traffic for her own safety.

Danny J. Bakewell Sr., executive publisher of the Los Angeles Sentinel, the city’s largest black-owned newspaper, said at the time that her decision was “unbelievable.” “No one who has seen the video tape needed a bias report to determine that the beating suffered by Ms. Pinnock was criminal,” he told his newspaper. “It was clearly a use of excessive force.”

Lacey has also drawn criticism for not yet announcing whether her office will charge two LAPD officers who shot and killed Ezell Ford, a mentally ill African American man who was stopped while walking home in South L.A. The Aug. 11, 2014, shooting came just two days after the controversial killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., and stoked protests over the deaths of black men by law enforcement.

Beck, the police chief, deemed the shooting justified, saying Ford had tried to grab an officer’s gun during a fierce struggle. The city’s Police Commission, however, decided that one of the officers had used such flawed tactics in the moments leading up to the shooting that his use of deadly force was ultimately unjustified.

Lacey has said prosecutors needed additional time to review evidence from a wrongful death lawsuit filed by Ford’s family before they can make a decision.

Her office is still reviewing a recommendation Beck made a year ago that Lacey prosecute Officer Clifford Proctor for shooting a 29-year-old man in Venice in May 2015. The LAPD chief said video evidence contradicted Proctor’s claim that he thought Brendon Glenn was reaching for his partner’s gun during a struggle with the officers. Glenn, who was unarmed, was shot in the back.

Lacey, 59, says her role in deciding criminal charges, as well as who she is as a person, have often been misunderstood.

She grew up in Los Angeles’ Crenshaw neighborhood in the 1960s and 1970s. She remembers seeing signs of violence all around — police once found a woman’s body on the corner near her home. She learned to look over her shoulder as she walked and said she didn’t realize, until moving to Irvine for college, that not everybody had bars on their windows for protection.

In 1983 — when Lacey was in her late 20s — someone spray-painted graffiti on a telephone box at her parents’ home. Her father painted over it and, before long, while he was mowing the lawn, someone drove by and shot him in the leg, she said. He survived, but the crime remains unsolved.

Her life experiences, Lacey said, shaped a deep respect for police.

“People in the community knew, ‘Hey, if something’s going on, call the cops,’” Lacey recalled.

But she also knew from a young age that it was a complicated relationship.

As a little girl, she said, she remembers watching the demonstrations led by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. on television. She said she can still see the image of police — acting as a shadow force of the Ku Klux Klan — using high-pressure fire hoses and attack dogs on African Americans.

“Impossible to forget,” Lacey said, wincing. “It’s recent, so I understand why there would be distrust of the police. I totally understand it.”

Before dropping off her son at Howard University in 2000, Lacey said she sat him down for a talk. Living in Washington, D.C., would be different than the sleepy Southern California neighborhood where he’d grown up. Because he was a 6-foot-4 ½-inch black man, she reminded him that the police would always watch him extra close. No matter what, she told him, don’t challenge them.

“If anything ever happens,” she warned him, “just please do what they say. Don’t start saying, ‘My mother is a lawyer. My mother is a prosecutor.’”

She returned to Los Angeles and did her best not to worry. Then, one day, she got a call from her son. He sounded shaken and told her that he’d been out for a walk with friends — other black men — when police swarmed around them, forcing them to lay face down on the ground. They spread their arms, her son told her, and waited as the officers patted them down. The officers eventually told Lacey’s son and his friends that there had been a robbery nearby and that they had fit the description of the suspects.

“I was just kind of glad he got out of that without…” Lacey said, stopping short of mentioning a shooting. “When you think about it: They have guns and you don’t.”

Lacey said she also understands the public’s gut reactions to police killings, especially ones captured on camera, because she, too, often finds herself making quick judgments after watching the news.

Take the South Carolina case of a white officer who fatally shot Walter Scott, a black man, in the back, while he was running away, or the choking death, of Eric Garner in New York City. Lacey said both stories disturb her, but that those cases differ from the ones in her jurisdiction in an important way: She doesn’t have all the evidence.

“It’s one thing to judge as a human being — to look at something and have a judgment,” she said. “It’s another thing to be the top prosecutor.”

For L.A. County cases, Lacey said she feels an obligation to reserve judgment and take as much time as she needs to methodically check the facts before applying the law. So far, she said, when she’s done that, she’s felt compelled not to file charges.

Back at the town hall in South L.A. in October, activists demanded charges against the officers who shot Ford. They chanted his name.

As a woman handed out fliers — which read “Lacey will prosecute people who leave their dogs in their car, but not Cops who Kill people!!” — a group of LAPD officers watched from a few feet away. Lacey stood with her hands clasped and frequently blinked, breaking her somber expression.

When the father of a man killed by a sheriff’s deputy spoke, he asked Lacey if she worked alongside Satan. And at one point, as the shouting grew louder, an organizer asked a respected pastor to bless the meeting.

“Father, we ask you for justice,” he prayed. Lacey, who wears a WWJD — What would Jesus do? — bracelet around her right wrist, nodded, mouthing, “Amen.”

When she took the microphone, it was dark outside and she was flustered.

“Good afternoon,” she said, catching herself. “Or, good evening.”

As she spoke about her job being “misunderstood,” the audience booed her. Her voice grew quieter, and she started to shift her weight from foot to foot — a woman told her friend that Lacey looked like a scared rabbit.

“I’m just one woman,” she said, “who’s trying to follow the law, who’s trying to listen, who’s trying to do the right thing.”

Eventually, Ebony Fay — a supporter of Black Lives Matter — took the microphone. After addressing the district attorney as “Sister Lacey,” Fay explained that she’d voted for her in 2012 because she had faith in her and thought she’d be fair. Now, Fay said, all she felt was disappointment. She had expected more empathy she told Lacey, from someone who looks like her.

Fay paused, locking eyes with Lacey: “When — not if — but when this city burns, it will be your fault.”

The crowd roared and Lacey stood, with her hands folded across her chest, and shot back: “You have been incredibly patronizing and insulting.”

Then, she walked out of her own town hall meeting.

For more news from the Los Angeles County courts, follow me on Twitter: @marisagerber

ALSO

New Orleans mayor announces $13.3 million in settlements over Hurricane Katrina police shootings

Family demands federal investigation after Bakersfield police kill 73-year-old man

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.