Here’s what happened in the last two LAUSD teachers’ strikes, in 1970 and 1989

- Share via

As the strike fever built, Los Angeles teachers assembled at Hamilton High School and solemnly placed a casket into a hearse.

The funeral cortege then headed to LAX with a message for Sacramento: Public education is dead.

For the record:

2:00 p.m. Jan. 11, 2019An earlier version of this article stated that the mock funeral for public education was a prelude to the 1989 strike. It took place in 1992, in response to state budget cuts.

That was an epilogue to the last strike by L.A. teachers, nearly 30 years ago, as the gains won were slipping away. Today, teachers are once again on the brink of a walkout, saying public education is in peril.

If the strike takes place Monday, as planned, it would be the third in the five-decade history of United Teachers Los Angeles.

The earlier strikes, in 1970 and 1989, brought turmoil to the school system and angst to the city as students languished at schools with light supervision, played hooky or demonstrated while union and district officials wrangled in court and in the media for the upper hand. The threatened walkout could do the same.

As in past strikes, the pay dispute is compounded by deeper battles over the stature of teachers and the funding of public education.

The district has offered teachers a 6% raise spread over the first two years of a three-year contract. The union wants an immediate 6.5% raise, retroactive to a year earlier.

Teachers have rejected the district’s limited offer to reduce class size and add more support staff and are demanding the reversal of years of cutbacks to “fully staff” schools.

The union’s rhetoric reflects a theme of teacher empowerment that has been at the center of the school district’s labor struggles going back to 1970, when UTLA members were off the job for nearly five weeks.

The lasting effects of the earlier strikes have been mixed. Teachers and their union gained stature after both strikes, but the underlying goal of solidifying the funding of public education has proved elusive.

“The open question is: Why in terms of money are not the two parties holding hands and getting on the plane to Sacramento?” said Charles Kerchner, a labor relations historian and professor emeritus at Claremont Graduate University. “The paymaster here is the state.”

He wondered whether a strike might undermine any effort to amend California tax law in ways that would allow LAUSD to “move up from the bottom 10 places in the country in terms of school funding.”

The same question infused the previous strikes.

In 1970, teachers won a 5% pay raise along with smaller classes and the creation of advisory councils on which they would share power with administrators — gains hailed as a watershed at the time.

“We have turned the school administrative system upside down, and teachers for the first time have achieved a dignity for themselves because they now speak to administrators as equals,” Don Baer, UTLA’s then-executive director, said at the time.

But others cried “sellout” because the walkout failed to wring new funds from Sacramento, where Gov. Ronald Reagan remained unsympathetic.

“We should have stayed out on strike until Gov. Reagan and the Legislature were forced to realize that education in California is a top-priority problem,” said a disgruntled teacher quoted anonymously in the Los Angeles Times.

The union victory was further compromised when a court found that California law did not authorize school districts to engage in collective bargaining and nullified the contract.

But the strike’s impact was felt years later, in 1975, when the Legislature approved the Rodda Act, establishing collective bargaining for teachers.

“That was my bill to protect the teachers and give them a voice and make sure the students that the teachers taught were listened to, so the winners of the strike have to be the students,” said Bill Lambert, a UTLA co-founder.

But the district’s funding problems grew worse as Proposition 13, the 1978 property tax reduction measure, cut into the primary source of local school funding.

Proposition 98, a teacher-backed initiative approved by voters a decade later, set minimum levels of state funding.

But the measure turned out to be a ceiling, not a floor, said Wayne Johnson, the fiery UTLA president who launched the 1989 strike.

‘’Education, unfortunately, has deteriorated to a terrible level in this city,’’ Johnson said during the strike, decrying “a badly underfinanced school system that suffers from a 40% dropout rate, overcrowded classrooms and shortages of school books and other supplies.”

The 1989 strike proved to be another contest for public opinion. In the run-up, the union provoked student protests by announcing that teachers would not file grades with the district.

The district and then-Supt. Leonard Britton overreacted by docking the pay of teachers who boycotted unpaid duties such as playground supervision and after-school meetings. Johnson successfully used media coverage to portray the union as the underdog.

Britton was a respected administrator who was sympathetic to the teachers’ goal of shared decision-making. But he did not understand that the politics of the district “was no longer that of an ‘all-powerful superintendent’ who was a benefactor of a comparatively weak teachers union,” researcher Stephanie Clayton concluded in a 2008 analysis of the strike for Claremont Graduate University.

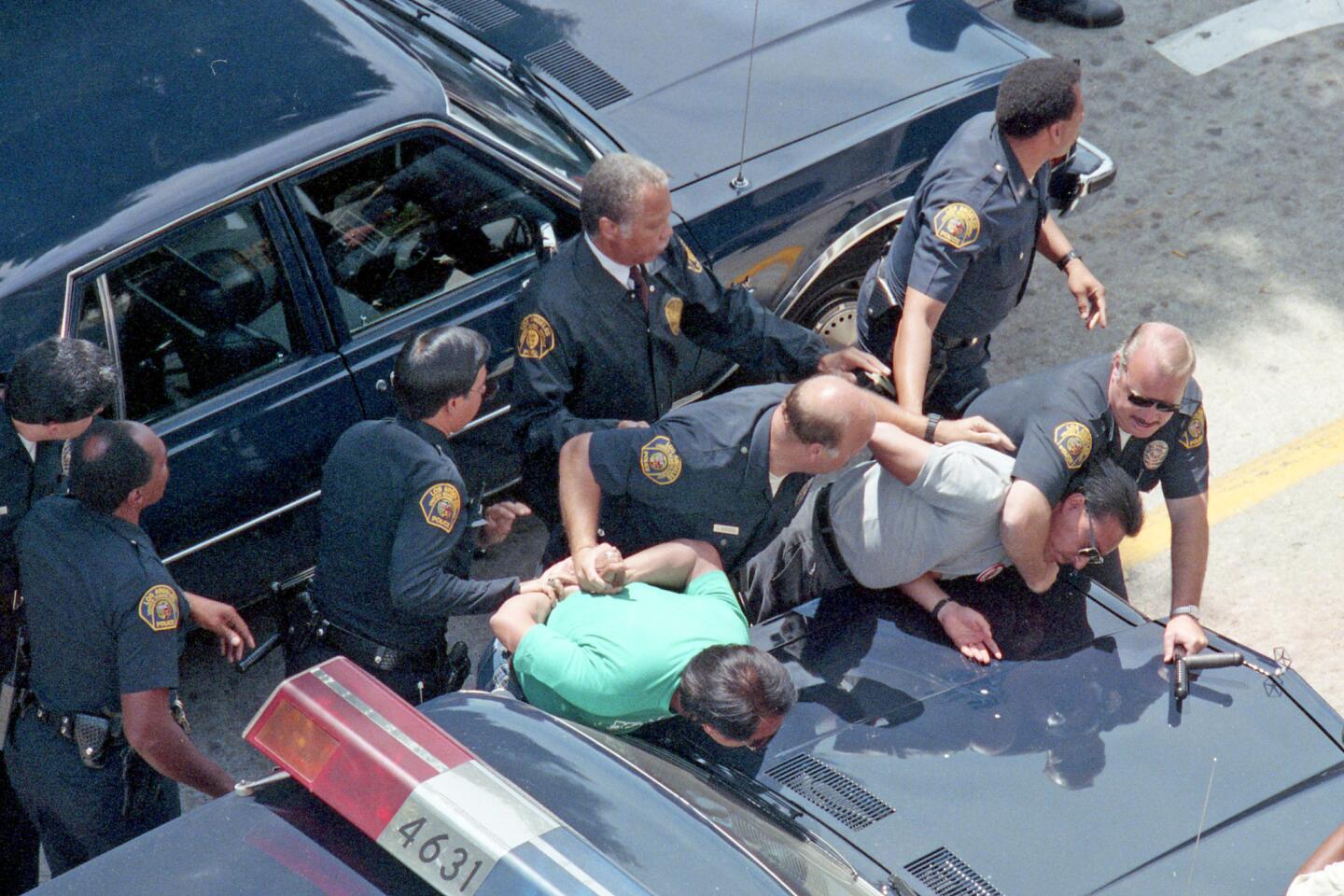

Demonstrations by teachers and students, some degenerating into rock-throwing by students, helped turn the tide toward the teachers.

The 1989 victory, like its precursor 19 years earlier, proved fragile. As the recession of the early 1990s plunged LAUSD into the red, teachers faced a 10% pay cut at the end of the contract.

A more far-reaching gain involved district politics. Elections shortly after the strike seated a union-friendly majority on the school board that added agency fees to the contract, allowing UTLA to collect dues from all teachers until the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the practice in 2008.

“UTLA got enough money that they bought their headquarters on Wilshire Boulevard,” Johnson said.

And the teacher engagement didn’t prove as big a hit as Johnson had hoped.

David Tokofsky, a young teacher who walked the picket lines in 1989 and later served three terms on the Board of Education, looks back on his time on school-based management committees as a waste.

“I could have been earning a master’s degree and I sat there arguing over small amounts of money,” Tokofsky said. “What was disappointing to me as a young teacher in 1989 is the class-size thing just melted away compared to the salary thing.”

Though three decades separate that strike from the current one, the underlying grievances, and the hostile rhetoric surrounding them, have hardly changed.

“Desperate, despicable people” was Johnson’s epithet for district officials when he told 7,000 teachers at a Sports Arena rally: “They are lying, they are lying, they are lying.”

Alex Caputo-Pearl, the current UTLA president, has called Austin Beutner, a businessman who had no experience in school administration before being named superintendent, an out-of-touch millionaire with “an agenda to dismantle the district.”

Hardball tactics took all three labor disputes into court. Teachers in 1970 ignored a Superior Court order declaring their strike illegal, ultimately resulting in $12,000 in fines for the union and five of its officers.

The union went to court in 1989 unsuccessfully seeking an order to prevent Britton from withholding pay from teachers who refused to turn in grades.

In the current dispute, the district asked a court, also unsuccessfully, seeking to require special education teachers to continue working during a strike, and the union went to court over the strike start date.

But Kerchner, the Claremont Graduate University historian, sees the background themes of past strikes as greatly magnified today because of changes in the city itself — no longer a mecca for socially engaged corporate leadership — and the emergence of charter schools.

“This is a strike about the soul of public education,” Kerchner said, calling it a contest between “two prophets” preaching opposite visions.

On the one hand, Caputo-Pearl “has a very clear idea of what he thinks schools in Los Angeles should look like, community schools with wraparound services.”

Beutner, he said, has been “manifestly unclear about his plan, but given who supported him … making a safe haven for charter schools is much more in his wheelhouse.”

For Tokofsky, this debate pits an unrealistic idealist against an unseasoned ideologue with a “lack of reality on both sides.”

“There is a lot of anger here that feels different,” Tokofsky said.

Johnson also sees the current situation as fundamentally different from the 1989 strike he led.

“UTLA keeps saying publicly it’s not about the money,” Johnson said in an interview. “With us, it was almost 90% about the money.”

H’

Teachers got an immediate bump of 16%, with another 8% the following year, he said. The 1993 pay cut clawed back about half the gain.

Johnson has no regrets.

“I want that on my tombstone,” he said.

Twitter: @LATDoug

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.