Must Reads: Firefighter suicides reflect toll of longer fire seasons and increased stress

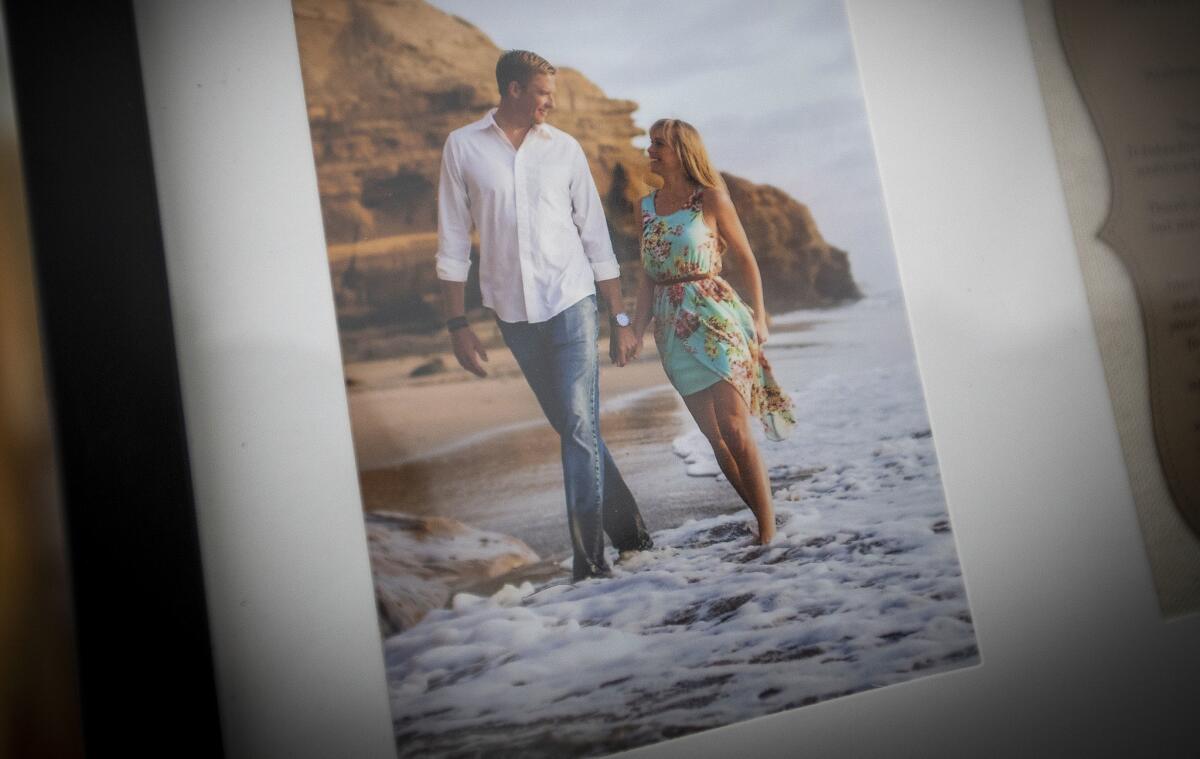

Capt. Ryan Mitchell had just finished three punishing weeks of firefighting. He had deployed to fires far from home, then returned only to dash out to another one.

Mitchell’s parents and 16-month-old son came to visit him at the station.

“He didn’t look good. He was tired, he was thin, his eyes were shallow. He wasn’t his usual self,” Mitchell’s father, Will, recalled.

Two days later, Mitchell reported to Cal Fire’s San Diego unit headquarters in El Cajon for his regular 72-hour shift.

After he finished, on Nov. 5, 2017, he drove east to the Pine Valley Creek Bridge, among the highest in the U.S.

He parked his car, walked to the edge of the bridge and jumped.

Mitchell, 35, was one of at least 115 firefighters and emergency medical service workers in the U.S. who died by suicide in 2017, according to data compiled by the Firefighter Behavioral Health Alliance, which tracks such figures nationwide.

The figure, probably an undercount, is a startling one, and one that many worry portends an epidemic as ever-lengthening fire seasons, more frequent mass casualty events and increased strain on emergency personnel take their toll.

The suicide rate among such workers has been estimated at 18 per 100,000 people, exceeding the rate in the general population of 13 per 100,000, according to a report by the Ruderman Family Foundation and federal data.

Documented suicides have been rising since around 2005 and exceeded 100 each year from 2014 to 2017, according to the behavioral health alliance.

More firefighters took their own lives than died on the job over that span, though line-of-duty deaths often eclipse suicides in the media and public consciousness.

A small but dedicated group of people in California and across the country is working to change that.

In the last few years these advocates have sought to increase awareness about firefighters’ mental health, pushed departments to offer more firefighter-appropriate help and stepped in as counselors themselves.

In Los Angeles County, Supervisor Kathryn Barger last year ordered the fire chief, sheriff and other first-response departments to review the behavioral health services offered to employees.

“These brave men and women are faced with grueling situations each and every day,” Barger said at a Board of Supervisors meeting.

“They sacrifice so much to save the lives of others,” she said. “It’s time that we pay them the same respect, and save theirs.”

In Mitchell’s case, there were no glaring signs of struggle.

Division Chief Daryll Pina, one of Mitchell’s mentors at the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, said the two had an hourlong conversation a couple of weeks before Mitchell died.

Mitchell, who had been a firefighter for more than 12 years, talked about the demands of being a captain, Pina said. He was thinking of applying for a transfer to work on a helicopter. And he had separated from his wife.

“But I never felt like he was at this point in his life, that he was struggling” with thoughts of suicide, Pina said.

Mitchell loved his job, his father said. A former U.S. Forest Service hotshot and an avid surfer, he was in great physical condition, too.

“Ryan wasn’t clinically diagnosed, was not regularly reaching out and asking for help, was not on drugs,” Will Mitchell said. “It’s just, something snapped.”

Firefighters and emergency medical services workers, like members of the military, routinely witness horrific, traumatic events — a daily reality not always understood by the public, psychologists say.

“It’s chronic, repeated exposure to everyone’s worst day,” said Sara Jahnke, director of the Center for Fire, Rescue and EMS Health Research at National Development and Research Institutes Inc., a nonprofit health research group.

On any given shift, that could mean a child drowning, a family killed in a car accident or an active shooter.

“And it all is happening in their backyard — not uncommonly to people that they know,” Jahnke said.

The nature of shift work can make things worse, as firefighters may be scheduled or recalled to work on holidays and birthdays, putting stress on family relationships.

The culture and expectations surrounding firefighters don’t help.

“When people call 911 they want someone there who’s going to be brave and heroic and handle the situation,” said Jeff Dill, a retired fire captain in Illinois who is a licensed counselor and founder of the Firefighter Behavioral Health Alliance.

Any time the stresses of the job get to be too much, Dill said, “we bury it.”

Secreting those stresses away, time and time again, eventually takes its toll.

Studies have shown that the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder, binge drinking behaviors and depression — each of which is associated with a greater likelihood of suicidal thoughts — is higher among firefighters than the general population.

Anxiety and sleep disturbances are also common, said Marc Kruse, clinical psychologist with the Austin Fire Department and Austin-Travis County Emergency Medical Services in Texas.

The issues are often intertwined.

“You can certainly imagine where difficulties within the job, perhaps not having effective coping strategies …would lead to post-traumatic stress or depression, which might result in alcohol use, which could lead to the end of a relationship” or loss of a job, Kruse said.

“If it cycles down, [that] could lead to someone attempting suicide,” he said.

According to one national survey of more than 1,000 firefighters, nearly half reported having suicidal thoughts. One in five reported planning a suicide.

In California and across the country, fire chiefs, labor leaders and counselors have committed new resources to support firefighters before they get to that point.

On a warm November afternoon, a white mobile trailer labeled “Woolsey Peer Support” was parked next to the briefing area at the Woolsey fire command post in Camarillo.

Lauren Dale, an ocean lifeguard specialist for the L.A. County Fire Department, walked the grounds approaching firefighters with a blank birthday card.

“Do you guys mind signing this?” she asked a group that had come from Texas to help fight the fire. “It’s for a captain who’s going to miss her kid’s birthday.”

Filling the card was just one task Dale had undertaken in her role as a “lead peer counselor” at the Woolsey fire. Her main responsibility was providing firefighters with informal, confidential, peer-to-peer counseling.

“A lot of it is just validating their emotions and trying to be empathetic,” Dale said.

Many of those fighting the Woolsey fire had responded to the Borderline Bar and Grill shooting in Thousand Oaks just 12 hours earlier. Some of their own families had to evacuate from the fire’s path, and several lost homes.

The firefighters recovered bodies, saw pets that had been trapped in pens and now walked family after family through the wreckage of their former homes.

Peer support helps firefighters cope.

“We’ve been there,” said Capt. Scott Ross, also a peer counselor. “We’ve been away from home as long as they have. We’ve seen devastation…. We’re a trusted friend and co-worker that understands what they’re going through, and that’s a big part of it.”

Sometimes peer supporters refer firefighters to professional counselors. When they do, it’s crucial that those professionals understand the job, firefighters say.

“Firefighters report they go into a counseling session and they start telling their story, and the counselor starts to cry because they’re unprepared for the level of traumatic experience that the firefighter has,” said Capt. Frank Leto, deputy director of counseling at the Fire Department of New York.

New York and Austin hire and train staff counselors like Kruse, but L.A. County relies on contract clinicians who have participated in ride-alongs and in-station briefings to learn about firefighters’ everyday experiences.

In San Diego and elsewhere in the state, Cal Fire has worked to beef up peer support and reduce the stigma around using it.

Jason McMillan, a San Diego-based Cal Fire firefighter and member of the honor guard, fought fires alongside Mitchell and engineer Cory Iverson, who died in the Thomas fire of 2017.

He recalled standing watch as Ashley Iverson bade goodbye to her husband.

“It was beyond emotional. And I knew there was nothing I could do or say to help her,” McMillan said. “There is no way really to deal with it.”

McMillan, 35, had extreme anxiety and was depressed. He had already been wrestling with his ex-wife’s miscarriage, their divorce and fear that he would never measure up as a firefighter.

The deaths of Mitchell, Iverson and other firefighters he knew personally put him over the edge.

“It was too close to home,” he said. “I would try to almost dodge going on fires or going on calls … because of being terrified.”

He got assigned a desk job but was paralyzed by the thought of returning to an engine. At one point he found himself sitting on his bed with a gun in his hand and thoughts of suicide running through his head.

“I could see myself sitting there doing it, but I wouldn’t do it,” he said.

In July, he told his chief he couldn’t return to work.

A peer supporter reached out and connected McMillan to a trauma retreat.

After McMillan returned, he posted a note on Facebook about his experiences. Will Mitchell responded, telling McMillan he was proud of him and glad another family wouldn’t go through tragedy like his did.

“That really hit home,” McMillan said.

The two are now joined in their mission to make firefighters more aware of behavioral health and to remove the shame associated with seeking help.

Will became a volunteer fire chaplain so he could offer help to firefighters in his son’s unit. McMillan, who returned to work in the fall, has made a habit of simply talking with his crew about the calls they go on.

In November, McMillan was sent to the Woolsey fire. One of his first assignments was to protect a nursery and avocado grove. The year before, Iverson’s strike team had been working near an avocado orchard when he became trapped.

“I heard ‘avocados’ and in my head was like, ‘Nope, I’m not doing that,’ ” McMillan said.

But this time he didn’t run or panic. He knew he could do the job.

Twitter: @AgrawalNina

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.