For Ghost Ship rescuers, a scene they can never forget

Brian Centoni of the Alameda County Fire Department recounts the night of the Ghost Ship warehouse fire in Oakland.

- Share via

Reporting from Oakland — The first body he saw, he recognized.

She looked like a mannequin under a pile of charred wreckage about a dozen feet high, among pianos, drum kits and amplifiers coated with soot.

As Brian Centoni carefully peeled away layers of debris, his body drenched in sweat under heavy fire gear, he realized he knew her face.

Hours earlier, the fire engineer had seen her photograph on the news. She reminded him of his wife. Same size, same race. She was somebody’s daughter. She was among those unaccounted for after a fire broke out during a concert at an Oakland warehouse known as the Ghost Ship.

She was the 31st victim authorities pulled from the rubble.

“This situation was just, like, ‘Wow,’ ” Centoni said later. “It just got real, real fast.”

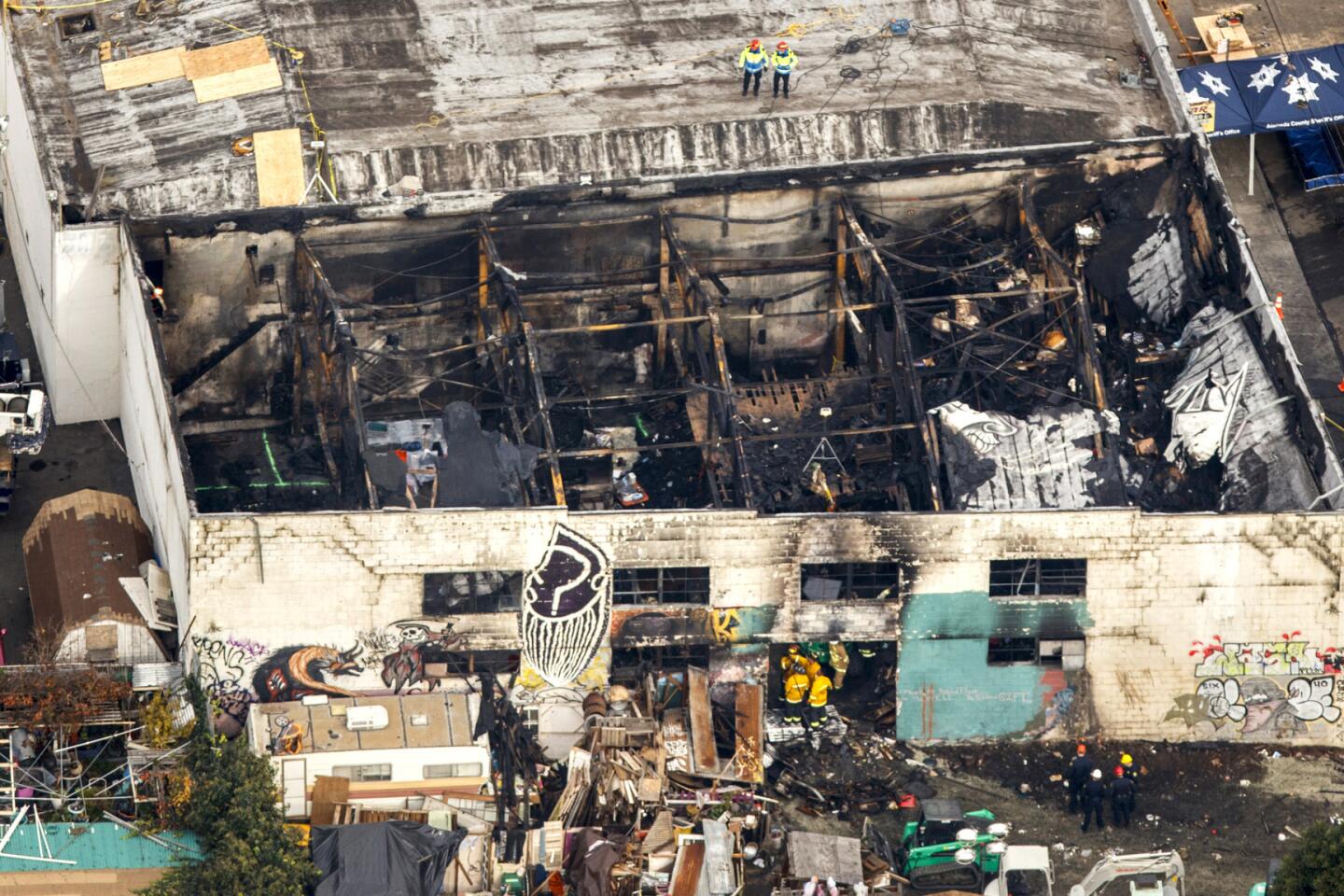

For days after the Dec. 2 fire, dozens of searchers fulfilled their grim mission in near silence. Some constructed wooden shoring to stabilize areas where the two-story building was collapsing, while others filled five-gallon buckets with blackened lamps, pieces of pallet furniture and horned skull masks while searching for bodies. The work was slow and somber, done mostly by hand, at times with shovels.

Centoni spent roughly three hours digging through the smoldering hulk of the massive Ghost Ship. These are hours neither Centoni nor other firefighters will ever forget.

“You go in there, you put your head down and you work,” said Brian Ferreira, a fire captain with the Alameda County Fire Department who spent several hours that Sunday sawing wood and hammering nails to build five large shores that could each hold roughly 16,000 pounds of weight. “We’re doing it with the intent to bring closure to those families, to bring them their loved ones.”

Sundays are typically quiet at Centoni’s Alameda County Fire Station No. 10, several miles from the East Oakland warehouse in neighboring San Leandro.

Centoni, a 36-year-old guitarist in a band with other firefighters, thought he’d squeeze in time between calls to catch the Oakland Raiders playing the Buffalo Bills on TV.

But about halfway into his 48-hour shift, Centoni’s crew got called to the warehouse fire.

A feeling of dread ran through him. He knew he’d be searching for the dead.

“I knew I was going to see young kids, artists and musicians — kind of like myself,” Centoni said.

But he thought of his father, a retired firefighter who responded to the World Trade Center with cadaver dogs two weeks after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, and felt proud to have been chosen for such a daunting task.

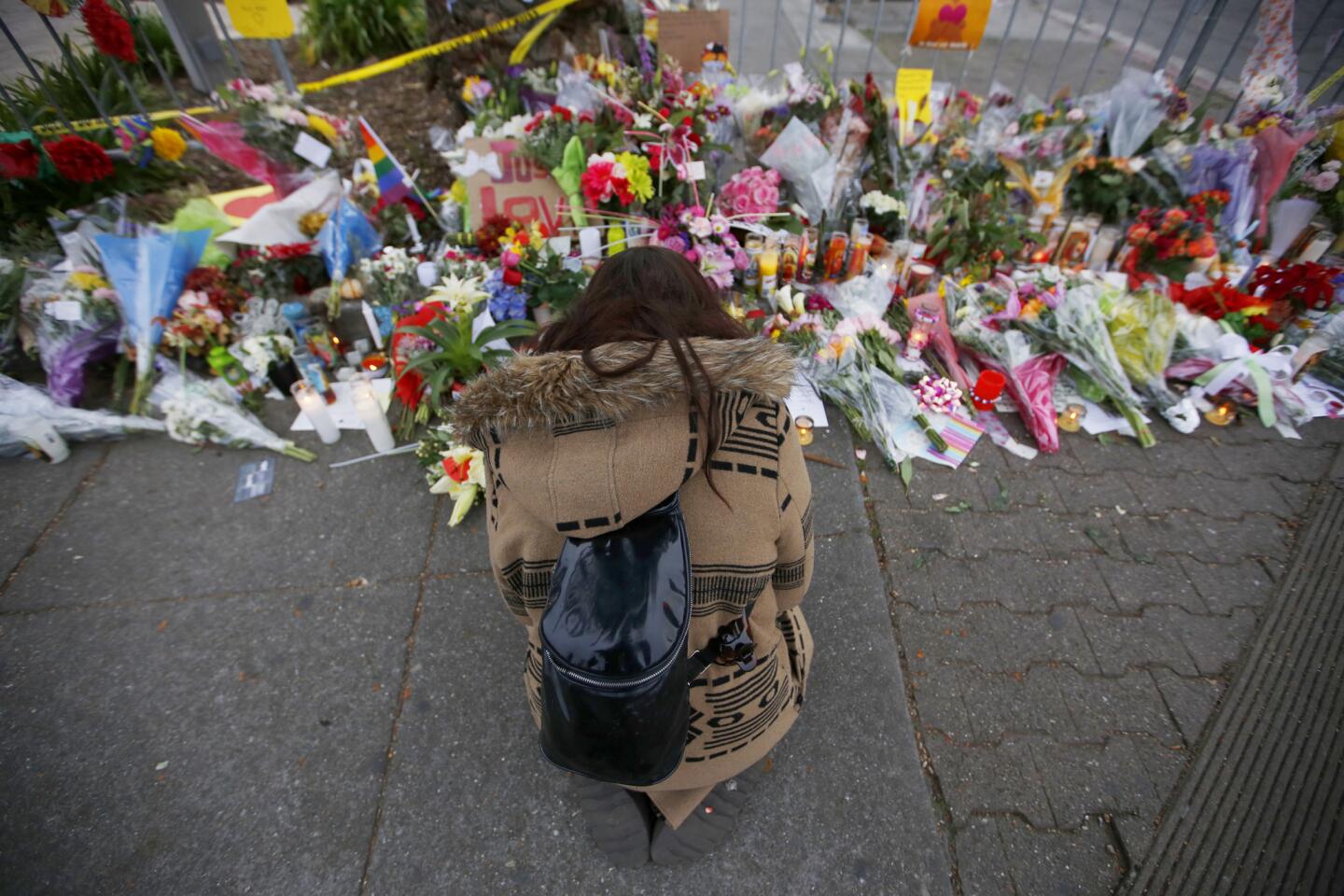

After a briefing, Centoni’s crew, including Capt. Bryan Dillingham and firefighter Brendan Burke, hopped on their rig and headed to Oakland Fire Station No. 13, where they swapped out their dress uniforms for their protective turnout gear. Centoni fastened his helmet and pulled on his gloves before walking a few hundred feet to the Ghost Ship, past people weeping and laying bouquets of flowers outside the building.

It felt eerie inside; smoke hung in the damp air. Reality struck when he glimpsed that first body. In that moment, he had no idea what the rest of the day would hold — whether he’d find one more body, or 20.

Coroner’s officials came over to snap photographs, looking for tattoos or piercings that would help verify the woman’s identity, before her body was carried to a more secure area.

As he dug farther down in the pile, Centoni noticed two more bodies. A man and a woman had fallen together from the second floor after flames climbed walls and caved in the roof. Authorities fished out their iPhones and wallets, still mostly intact.

“They really had no chance,” Centoni said. “The fire just snuck up on them so fast.”

If only the fire broke out at a different hour, he thought, when the warehouse wasn’t filled with people.

“It just trips me out how everything lined up perfectly to have this tragedy happen,” Centoni said. “It was basically a burial ground for these people.”

With his face coated with dirt and ash, Centoni took a break that Sunday afternoon to hydrate. He almost couldn’t eat after what he’d seen, but he felt fatigued and hungry. He scarfed down tacos and water, washed up and waited to see if he’d be sent back inside.

He wanted to go back in, he told his captain. He wanted to help.

Another round of digging followed, but he found no other bodies.

By that night, Centoni had returned to his regular fire station. He threw his dirty turnouts in the wash and, after showering, changed into a spare set.

Another emergency call came in. Someone was having chest pains.

With his muscles sore and a trace of soot still on his face, Centoni jumped into Engine 10 with his crew and rolled out.

“It was like nothing happened,” he said.

Emotion would seep through later, triggered by a news alert, a mindless cleaning task, a photograph.

“Firefighters are faced with horrific things on a daily basis: victims of fires and auto accidents and medical emergencies,” said Alameda County Deputy Fire Chief Jim Call. “It can weigh heavy.”

Waking up at his regular fire station Monday morning, Centoni glanced at his cellphone while still in bed. An alert had come in from KTVU: Three more bodies had been recovered from the Ghost Ship. The final death toll would be 36.

Centoni’s shift was over at 8 a.m. At home, he hugged his 8-year-old son and 5-year-old daughter a little tighter than usual. When he’d picked up his daughter from school, a teacher walking with a line of students saw him, stopped and asked, “Were you on Engine 10 yesterday?”

He said yes, and she gave him a hug.

Centoni spent his day off cleaning out his music studio, thinking of the victims as he moved his own amplifiers and cables, equipment that resembled the ruins he’d spent hours sifting through the day before.

Later, he recorded a song called “Eureka” for his reggae-rock band’s upcoming album. It was almost as if he was recording the song for them, he said, those lost in the Ghost Ship.

“You see how creative these people were; everybody’s super talented — DJs, artists, beatboxers — all super talented people that loved music,” Centoni said. “I almost could’ve saw myself in this place.”

alene.tchekmedyian@latimes.com

Twitter: @AleneTchek

ALSO

After Ghost Ship and a crackdown, L.A.’s DIY music scene plans its response

Ghost Ship fire mystery: What did fire officials know and when did they know it?

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.