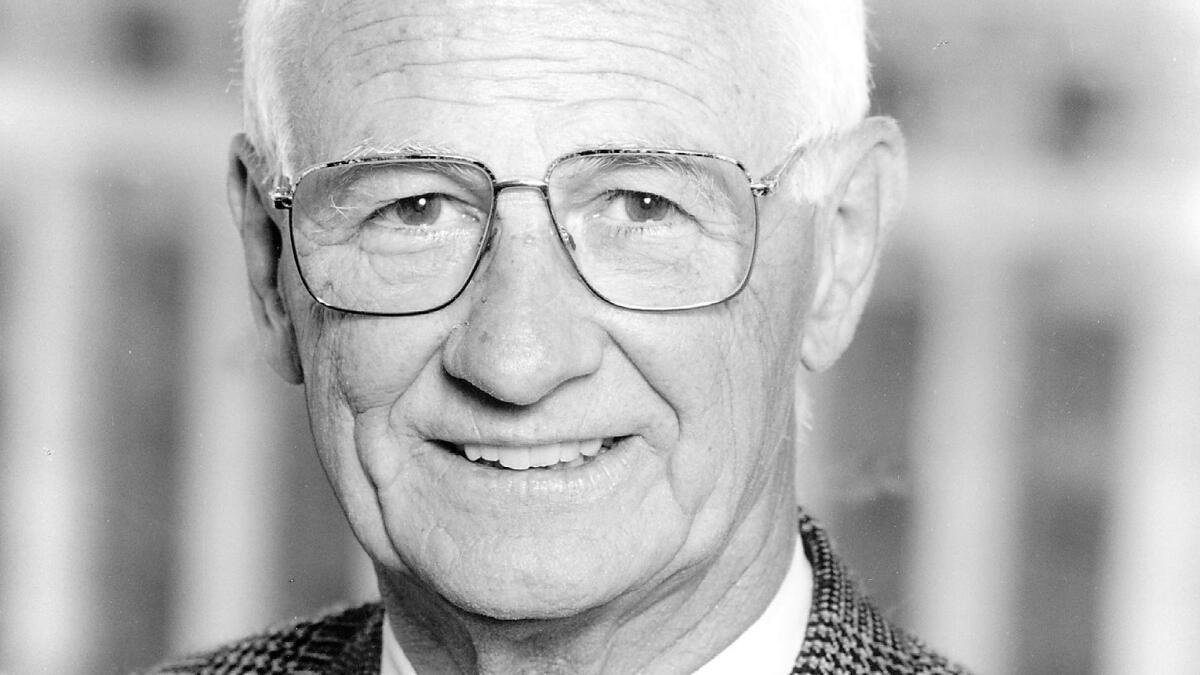

Judge William A. Norris, author of early ruling that boosted gay rights, dies at 89

- Share via

William A. Norris, a former federal appeals court judge who wrote an iconic ruling on gay rights long before same-sex marriage entered the lexicon, has died. He was 89.

Norris died Jan. 21 at his home in Bel-Air, surrounded by family and listening to his favorite big band music, said Kim Norris, his daughter. He had been hospitalized for several days before his death because of difficulty breathing. Kim Norris said her father died of congestive heart failure.

While serving on the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, William Norris, who was appointed by President Carter, authored a majority decision that said gays had the same constitutional protections as racial minorities.

The case, Watkins v. United States Army, overturned the mandatory discharge of Staff Sgt. Perry J. Watkins for acknowledging he was gay.

Norris’ ruling has been described as the first to use an equal-protection analysis in the context of gay rights. It foreshadowed the Supreme Court’s affirmation of same-sex marriage 27 years later.

A larger 9th Circuit panel decided to reconsider Norris’ decision. That panel ruled for Watkins, but avoided Norris’ constitutional analysis, which was not in step with U.S. Supreme Court precedent at the time.

“He was a big hero in the gay community for that opinion and for advancing the constitutional theory ahead of its time,” said 9th Circuit Judge Raymond Fisher, who practiced law with Norris before his career on the bench.

“It sent a signal to the gay community that there was support in the federal courts,” said Fisher, a President Clinton appointee. “There was hope.”

Norris also was active in political and civic affairs before joining the 9th Circuit in June 1980 and after retiring in October 1997.

He was an optimist who always expected things to go well, Fisher said, recalling trying an antitrust case with Norris before they became judges. Norris was certain they would win, Fisher said.

“Even when the jury came in against us, he was able to find a silver lining,” Fisher said. “He said we held the damages to one-third of what the plaintiffs thought they were going to get.”

Norris served on the California Board of Education from 1961 to 1966 and the Board of Trustees of the California State Colleges from 1966 to 1972.

A delegate to several Democratic National Conventions, Norris was with Sen. Robert Kennedy at the Ambassador Hotel hotel in Los Angeles in 1968 the night Kennedy was assassinated. Norris took to the stage to try to calm the alarmed crowd after the shooting.

He ran unsuccessfully for California attorney general in 1974, losing to Republican incumbent Evelle J. Younger.

He helped elect Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley, who later appointed him president of the Los Angeles Police Commission, and Wilson Riles Jr. as California’s Superintendent of Schools.

Norris also helped establish Los Angeles’ Museum of Contemporary Art, serving as the founding president of the museum’s board of directors from 1980 to 1992.

Philanthropist Eli Broad, who worked with Norris to establish MOCA, said Norris was “a good man who loved Los Angeles.”

“I always admired his civic dedication, leadership and integrity,” Broad said. “Deeply principled, he was a great lawyer and judge who became a leading liberal voice for our country.”

Although Norris wrote about 400 decisions on the 9th Circuit and possessed strong legal and strategic skills, “his love was politics, there was no doubt about that,” Fisher said.

“That is ultimately why he left the 9th Circuit,” Fisher said. “He felt as a judge that he lost his 1st Amendment rights to go out and speak his mind.”

Norris helped build a thriving appellate practice at the Akin Gump law firm after leaving the court and served as a confidante to many public officials. When Barack Obama ran for president, Norris made campaign calls to voters in Pennsylvania, where he was born.

Norris also was an expert skier who raced the slopes until he was 78, stopping only after being injured in a collision with another skier.

Kim Norris recalled that her father loved hosting regular Shabbat dinners with Jane Jelenko, his wife of 27 years. He had been married and divorced twice before.

Their 10 or so dinner guests would include people from the art, legal, entertainment and corporate worlds. Leonard Nimoy of “Star Trek” was often at the table.

“Dad would sit at the head of the table,” Kim Norris said. “His role was to make sure everyone had a chance to say something interesting. He loved those dinners.”

Norris, the son of English immigrants, was born on Aug. 30, 1927, and grew up in Turtle Creek, Penn. He planned to become a journalist, writing stories for a weekly newspaper his father managed and later freelancing for other publications.

After a stint in the Navy, Norris used his GI bill benefits to attend Princeton University. A professor persuaded him to apply to law school.

He graduated from Stanford Law School and clerked for Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas.

In addition to his wife and daughter, Norris is survived by his son, Don Norris; daughters Barbara and Alison Norris; stepchildren David Jelenko, Jill Bauman, James Weister and Joni Martino; two grandchildren, Nathan and Semantha Norris and a sister, Dorothy Lankford.

Plans for a memorial service are pending.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.