The Valley will get light rail: Metro board approves north-south line along Van Nuys Boulevard

- Share via

For nearly two decades, residents of the northern and eastern San Fernando Valley watched as Los Angeles County officials opened new rail lines to the Westside, the San Gabriel Valley and East Los Angeles, hoping that the Southland’s transit building boom would someday reach them, too.

Thursday, they received a clear sign that it will. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority voted unanimously to bring a light-rail line to the East Valley, addressing long-standing complaints that transportation officials have neglected the needs of a poor, transit-dependent swath of the county.

For the record:

6:55 p.m. June 28, 2018An earlier version of this story misspelled Metro director Jacquelyn Dupont-Walker’s first name as Jacqueline.

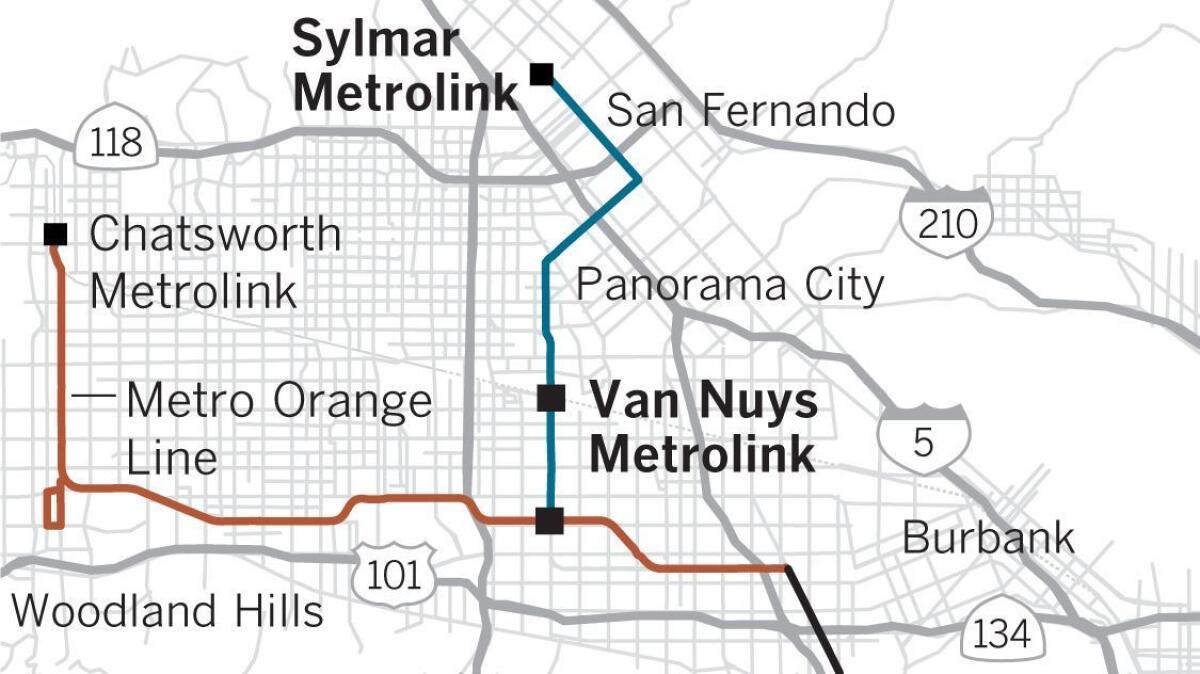

The $1.3-billion rail line will run along Van Nuys Boulevard, the street most synonymous with the Valley’s post-World War II car culture. The line will add 14 stations in Van Nuys, Panorama City, Arleta, Pacoima and San Fernando to the county’s growing rail network.

Metro officials had originally recommended enhanced bus service along Van Nuys, frustrating residents who watched a rail line with far lower ridership projections win approval in the San Gabriel Valley. Advocates lobbied for a rail route, eventually securing $810.5 million through Measure M, the tax increase that passed in 2016.

“We have a long way to go before the East Valley is served with the kind of transit it deserves,” Coby King, the past chair of the Valley Industry & Commerce Assn., said at a Metro hearing last week. But, he added, the Van Nuys line is “a huge step.”

Construction on the line is scheduled to start in 2021, with passenger service slated for 2027. Officials hope that the Van Nuys line and the Orange Line dedicated busway will carry spectators to the Sepulveda Basin to watch equestrian events and canoeing during the 2028 Summer Olympics.

But the rail line’s most important purpose will be serving the more than 62,000 residents of Pacoima and other areas of the northeast Valley who are transit-dependent, officials said. The Van Nuys corridor has the seventh-highest transit ridership in the county, and the line will carry an estimated 47,000 daily trips by 2040.

Rail service could also stitch together the Valley’s other transit options. Officials have planned for transfer points with the Orange Line and Metrolink stations in Van Nuys, and the Metrolink station in Sylmar.

The Van Nuys line will also serve as a key piece of Metro’s plans to bring rail transit to the Sepulveda Pass. Early route options suggest the route could run from Westwood or West L.A. through the Santa Monica Mountains and terminate at a station on the Van Nuys Boulevard line.

The rail line will mark a new chapter for Van Nuys Boulevard, once the heart of the Valley’s cruising culture. Starting in the 1950s, carloads of teenagers took over the street every Wednesday, Friday and Saturday night.

Residents said they hoped the line would also help the area return to its roots as a destination for shopping, dining and retail — perhaps chasing away some of the check-cashing stores and bail bond shops that dot the blocks surrounding the Van Nuys Civic Center.

“Things have changed, particularly in the North Valley,” said Francine Oschin, a transportation advocate. Her family ran a savings-and-loan on Van Nuys Boulevard more than five decades ago, when it was “vibrant and alive,” she said.

Community advocates said they welcomed investment in better transit, but that they were concerned that more development near the rail line could drive up rents, forcing out longtime residents. The share of residents who live below the poverty line along the rail route is three times the county average.

“We need to make sure that the benefit is inclusive of all of the community,” said Faramarz Nabavi of the Transit Coalition, a Valley-based nonprofit. He urged Metro to pursue housing cooperatives or affordable developments that could assist any tenants displaced by rising rents.

Just five years ago, building light rail in the Valley was impossible. For more than two decades, a state law known as the Robbins bill — named for its sponsor, former state Sen. Alan Robbins — banned above-ground rail through North Hollywood and Van Nuys. The law was reversed in 2014.

Even after the law was struck down, Metro had planned to run 2.5 miles of the line underground, with subterranean stations at Sherman Way, Roscoe Boulevard and the Van Nuys Metrolink stop.

Officials discarded those plans Thursday, saying they would have doubled the project’s cost while shaving only 90 seconds to two minutes from the line’s 31-minute route. The Van Nuys line will run entirely at street level, which is much cheaper but can create problems.

The Blue Line, which runs at street level along most of its route, has one of the highest fatality rates of any U.S. light-rail line. Commuters frequently face delays when trains strike vehicles or pedestrians on the tracks.

Running a train line at street level “can be a challenge to operate reliably in real-world traffic conditions,” Metro director Jacquelyn Dupont-Walker said during a meeting last week. She questioned whether Metro’s trains would be forced to wait at traffic lights, as they do along portions of the Expo and Blue lines.

The city of Los Angeles controls the traffic lights along the majority of the Van Nuys route, and will decide whether trains will be forced to wait at red lights with passenger vehicles and trucks, said Metro transportation planning manager Walt Davis.

“Behind the scenes, we’re hopeful that we can secure greater signal priority” than on previous projects, he said.

Board member and Duarte Mayor John Fasana questioned whether Metro’s plans for the line include enough passenger capacity. The plans call for 270-foot platforms at stations, which would accommodate three-car trains that carry up to 400 passengers.

Many platforms in the Metro system can’t support longer trains because they’re not long enough. In areas where rail lines run at street level, longer trains could block multiple intersections at once, impeding traffic.

“I think it’s important to at least look at, to have the extra capacity,” Fasana said.

For more transportation news, follow @laura_nelson on Twitter.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.