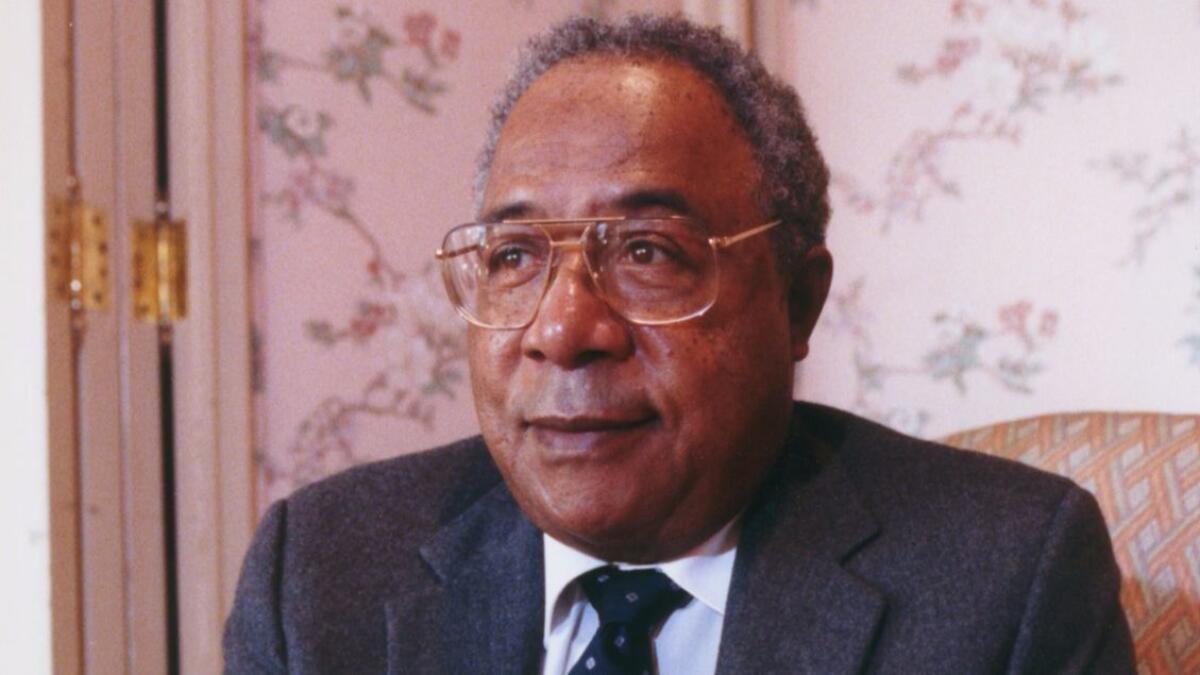

From the Archives: ‘Roots’ Author Alex Haley Dies of Heart Attack at 70

- Share via

Alex Haley, whose epochal pursuit of his roots brought the black experience into the hearts of hundreds of millions, died early Monday in a Seattle hospital. He was 70.

The Pulitzer Prize winner’s novel, “Roots: The Saga of an American Family,” produced a swelling of pride among blacks, brought enlightening entertainment to countless others, and painted broad smiles on the faces of television executives when the final episode of a miniseries based on the book attracted more than 100 million viewers.

A spokeswoman for Swedish Hospital said the onetime Coast Guard cook was admitted to the emergency room late Sunday night and died shortly after midnight.

Haley, whose other works include “The Autobiography of Malcolm X,” died of cardiac arrest, said Jane Anne Wilder of the hospital staff.

Haley was in Washington to speak at a banquet tonight at the Bangor Naval Submarine Base. He had been staying in an apartment in Seattle when he was stricken. Family members said Haley suffered from diabetes and a thyroid condition that could have contributed to the attack.

Haley came to writing relatively late in life after a military career. Although he had written for magazines, it was his meticulously researched quest for his mother’s forebears that brought him the 1977 Pulitzer Prize and the gratitude of blacks around the world.

“It was the story of our people. It was the story of how we came from Africa,” said Benjamin Hooks, executive director of the National Assn. for the Advancement of Colored People, from his Baltimore home. “The facts about the extended family he grew up in and that most black families grow up in is so important.

“He was truly a gifted person who wrote a book that was monumental,” Hooks added.

The 12-hour miniseries that evolved from Haley’s yearslong quest drew the then-largest audience in American television history, and millions more saw it when it was sold to television stations around the world.

Originally broadcast over eight nights in 1977, it was rebroadcast in its entirety a year later, attracting additional millions, and again last month on cable TV.

Although the last segment of the series has been surpassed by the final episode of “MASH” and the “Who Shot J.R.?” thriller on “Dallas,” each of the eight episodes remains among the top 50 shows ever broadcast.

Haley’s combination of fact and fiction set forth his tribal origins in Gambia, West Africa, his ancestors’ capture by slavers and their subsequent evolvement to a limited freedom in America. It sparked an unprecedented interest in genealogy.

Time magazine said the TV production will go down in history as a “special place” in black culture.

Critic Edmund Fuller said the book “Roots,” which was reprinted in 37 languages, not only confirmed a sense of continuity for black Americans, but was a useful reminder to whites of how the histories of both peoples are inextricably linked.

ABC executives originally planned to air the episodes once a week, but decided that black material would not attract predominantly white audiences stretched across several weeks of prime time. They compressed the time frame to minimize their gamble.

Perhaps the series’s ultimate testimonials came from restaurant owners, theater managers and taxi drivers who said their business was almost nonexistent while it aired.

Haley had spent 12 years writing and researching “Roots,” traveling half a million miles, talking with a tribal griot, or oral historian, in Gambia and poring over papers in more than 50 libraries on three continents.

As part of his research, he booked passage on a freighter from West Africa to the United States, sleeping each night in the belly of the ship on rough boards.

He said he wanted to imagine what it was like for his ancestors “to lie there in chains, in filth, hearing the cries of 139 other men screaming, babbling, praying and dying around you.”

Asked if he had ever anticipated the book or the miniseries’ success, the bespectacled, stocky author replied: “No, if I had, I’d have typed a whole lot faster.”

Haley’s success never seemed to interfere with his commonality and interest in all peoples.

John Rice Irwin, founder-director of the Museum of Appalachia in Norris, Tenn., and a friend of Haley’s since 1982, recalled a time when the author disappeared during a lunch in New York with the editor of a national magazine and a number of celebrities.

“Someone looked back in the kitchen and he was signing autographs for all the cooks,” he said. “He spent more time doing things and talking with common people . . . the people at the gas pumps. He wasn’t impressed with celebrities.”

Many years ago he visited The Times, a return to his roots as a journalist, he said during an informal tour. Several writers and editors had brought copies of “Roots” for autographs. And although he was pressed for time, Haley asked each for the names of their children and a little about them. He then inscribed the books to those children, writing a message to each.

Alexander Palmer Murray Haley was born in Ithaca, N.Y., and grew up in the west Tennessee town of Henning. He said he was inspired to become a writer by the stories told by his older relatives.

His grandmother’s and great-aunts’ storytelling led Haley to meticulously trace his mother’s side of the family back six generations.

He was to become in demand as a speaker, earning about $250,000 a year, and loved to tell audiences of those boyhood days when these “gray-haired grandmotherly ladies,” in their front-porch rocking chairs, would dip snuff and swap stories about Chicken George, a gamecock fighter, or Kunta Kinte, Haley’s great-great-great-great grandfather. Or Kinte’s slavery mentor, Fiddler, and their other larger-than-life forebears.

“When they talked about Kunta Kinte, ‘the African,’ ” Haley would say, it was “almost like they were talking about somebody in mythology.”

Haley—who said he was never much of a student and often embarrassed his father with his grades—enlisted in the Coast Guard in 1939 as a mess boy.

“I specialized in leftovers,” he would say of his cooking career. “I could make anything taste better the third day than it did the first day.”

He discovered a talent for writing at about that time and would compose love letters for the other sailors on the ship--for 50 cents.

Haley ended up serving 20 years in the military before being discharged, as a journalist, and starting a magazine writing career.

His first book, “The Autobiography of Malcolm X,” sprang out of a series of Playboy interviews Haley conducted with the Black Muslim leader who was assassinated in 1965. That book sold more than 6 million copies in eight languages. “Roots” sold 4 million in paperback and 200,000 in hard copy.

He also had a famous Playboy interview with George Lincoln Rockwell, then the leader of the American Nazis, and another with jazz legend Miles Davis.

Haley said in a 1988 interview that he was able to become a writer because his father had by sweat and determination worked his way out of sharecropping for white farmers.

“I was a sailor, I was a cook and this ‘n’ that, and it might be said I was bootstrapped up to being a writer, but the real bootstrapping was that which preceded me,” he said.

Haley’s father worked several jobs at once to support himself while he attended high school and college. He later became a railroad porter. A passenger who learned of the financial troubles he was having volunteered to pay his college expenses at North Carolina A & T, and Haley’s father went on to become dean of agriculture at four colleges.

After the publication of “Malcolm X,” Haley was given the first of 37 honorary doctorate degrees, from Howard University.

Haley said he could not wait to take his father to the award ceremony but the older man was not impressed.

“Typical of my father, he said it wasn’t earned.”

Not everyone was overwhelmed by the “Roots” mania that swept the country. A few scholars faulted its fictional approach to black history; some writers said portions of it were plagiarized, and eventually Haley had to fight off eight lawsuits, settling one (brought by the author of “The African,” who said Haley had lifted portions from that book) for about $500,000.

Although born in the North, Haley always professed his fondness for the South:

“I find that Southern-born people, white or black, tend to be better raised than people from other sections,” Haley once said. “Grandma taught me like that. I don’t do everything she’d want me to do, but I don’t get too far afield of her.”

Haley said his grandmother, who raised him after his mother died when he was very young, also would not have approved of four-letter words or sex scenes, so “Roots” had neither.

Haley is survived by his third wife, My, a son, two daughters and four grandchildren.

Last month, Haley announced that he was giving up life on his Tennessee farm to devote more time to writing. He had put the 127-acre farm in Norris, about 20 miles north of Knoxville, up for sale, asking $1.25 million. In his home there hung a fancy glass frame containing two old sardine cans and 18 cents, a reminder of the time when that was all Haley owned in the world.

Haley spent much of his later years at sea, shipping out on old freighters where he could write without being interrupted. Those were his most creative moments, he said.

His “A Different Kind of Christmas,” the tale of a slave’s escape on the Underground Railroad published in 1988, was written on a freighter trip from Long Beach to Australia.

Herman Gollob, his editor at Doubleday, said Haley could only write at sea because he would get too distracted on land. “He was a wonderful man, the most unaffected man you could meet. He loved talking to people and telling stories,” Gollob said.

“At sea, I will work from 10 at night until daybreak,” Haley told one interviewer. “Then comes that magic moment when you start to dream about what you are writing, and you know that you are really into it.”

At his death, Haley was planning another epic, this one a book on his hometown, Henning, which he said was being written “with absolute love.”

He conceived it as another tribute to those who had made possible his own success.

As he told Parade magazine in 1982:

“I urge (audiences) to tell their parents, grandparents and other living elders simply ‘thank you’ for all they have done to make possible the lives they now enjoy.”

Times researcher Doug Conner in Seattle contributed to this story.

From the Archives: Debonair Actor Joseph Cotten Dies at 88

From the Archives: Ossie Davis, 87; Actor Played a Powerful Role in Civil Rights Gains

From the Archives: Sarah Vaughan, ‘Divine One’ of Jazz, Dies at 66

From the Archives: His popular novels blended social criticism, dark humor

Actress Julie Harris dies at 87; Tony-winning Broadway star

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.