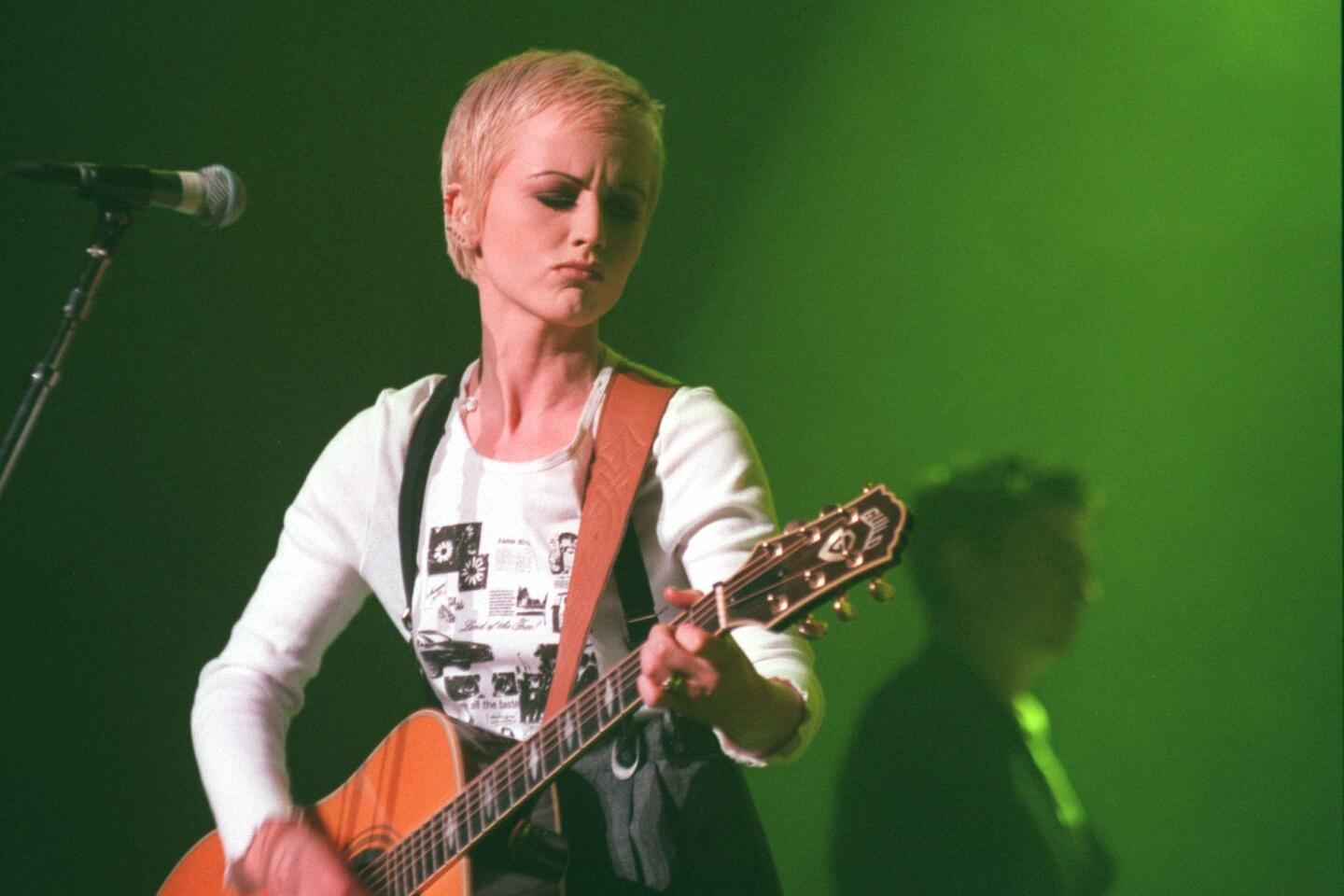

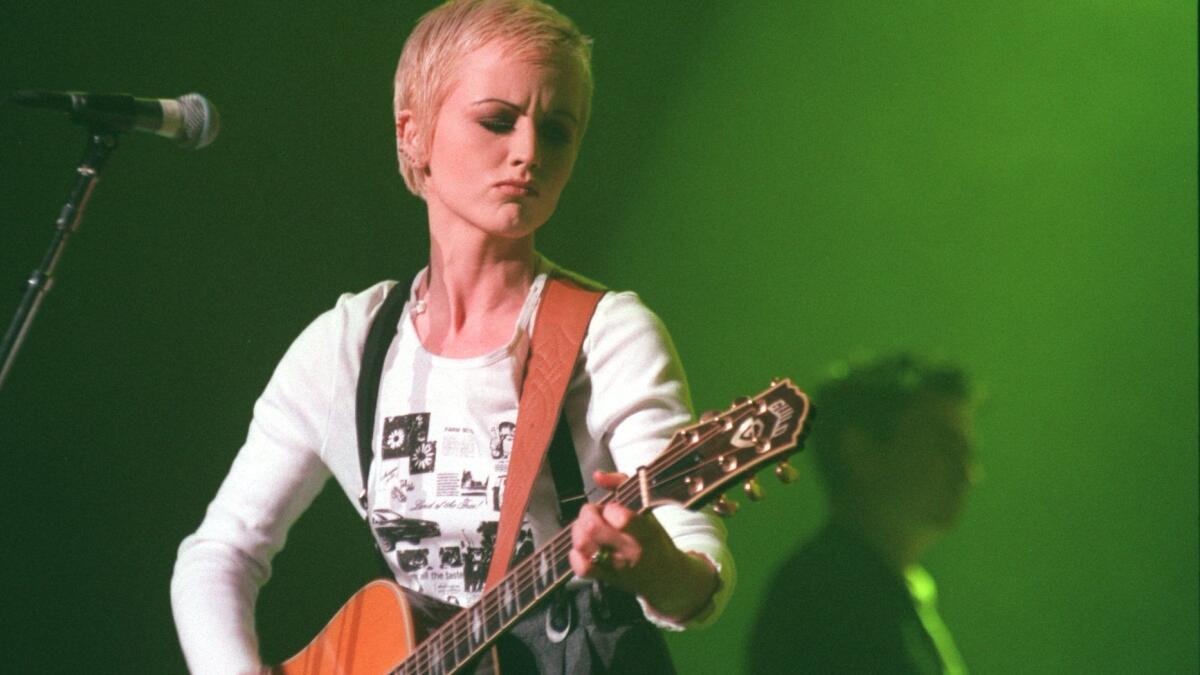

From the Archives: ‘Passionate, headstrong and determined.’ That’s how Dolores O’Riordan’s bandmates described her in 1994

- Share via

Editor’s note: Dolores O’Riordan, lead singer of the Cranberries, died in London on Jan. 15, 2018. She was 46. In 1994, she gave music critic Jon Bream an interview leading up to the Cranberries’ performance at the Wiltern Theatre. This story originally ran in The Times on Nov. 27, 1994.

‘Tis the season of the cranberry, and this year, Ireland’s Cranberries know it. They’re red hot.

The rock quartet learned about Thanksgiving and cranberries last year when it came to the United States for a fall tour after its tunes “Dreams” and “Linger” had jumped from college and alternative radio into the Top 10 on the pop charts.

Now the band is back in the country for another cranberry-season tour that will include stops Tuesday and Wednesday at the Wiltern Theatre (they’ll be back to play KROQ’s Christmas concert on Dec. 11). And once again, the Irish group has scored big with an alternative anthem, “Zombie,” that is making a splash on pop radio as well.

“We’ve been told that it’s the most played song ever on alternative radio in the history of America,” Cranberries lead singer and lyricist Dolores O’Riordan says matter-of-factly. “That’s exciting.”

It’s exciting to the Cranberries because after the irresistibly dreamy pop of last year’s hits and the subsequent 2 million sales of their debut album, “Everyone Else Is Doing It, So Why Can’t We?,” they didn’t want to be considered just a pop band. In fact, Island Records hasn’t even released “Zombie” as a single to U.S. stores. The label simply didn’t want the industry to typecast the Cranberries as a Top 40 act.

For the band, it’s a question of credibility.

“We’re not just another pop band,” declares drummer Fergal Lawler. “Most pop bands are laughed at; most of them are false people who just want to make money and sell lots of records and that’s all they’re interested in.

“Then you can go to the other extreme of being so alternative that no one buys your records. Luckily, we’re kind of in the middle. We’re a mix of pop, rock and alternative, I suppose. You can be successful and write really good songs and good music.”

O’Riordan, drinking tea in a hotel restaurant on the afternoon of their sold-out concert at the Orpheum Theatre here, even disputes the idea that “Linger” is a “pop” song. “I think Patsy Cline could have sung ‘Linger’ in good fashion. I think you could sing a good blast of it without any music. This group is based on songwriting.”

Like the Cranberries’ other hits, “Zombie” is catchy. But this time the quartet has a serious message. The song speaks about terrorists who killed innocent bystander children in a bombing.

O’Riordan says such an incident happened a few miles from them while they were on tour in England.” (The song) was about how adults argue over territory, which happens everywhere. Women and kids suffer the most while these big boys in green suits or whatever go around fighting for territory. At the end of the day, the world is the world. It’s ours...why can’t we share it and shut up?

I know war has been going on for centuries and centuries, but we’re supposed to be getting more civilized.

— Dolores O’Riordan on the song “Zombie.”

“It’s basically about human life, especially kids’ life. I just cannot accept children being slaughtered at the hands of political violence. I had a little brother and he died at birth. And we have a clock in my house with his name on it. Even though I never met him—he died before he came home—his presence is always in our house. It’s a sad thing when what could have been a life is taken. But then you think of a 3-year-old who was bringing happiness and was the center of a household—just gone.”

Of “Zombie,” O’Riordan says she hopes “it might make people reflect a bit on our society and what we’ve become. I know war has been going on for centuries and centuries, but we’re supposed to be getting more civilized.”

The Cranberries’ music has an unmistakable Irish undercurrent. It’s partly O’Riordan’s quivering wails, partly her Irish lilt or hiccup when singing at full volume, and partly the beauty of Irish folk music on the slower tunes. The Cranberries’ music is a swirling blend of the delicate, the elegant and the assertive.

Those adjectives also apply to O’Riordan, who is described by her bandmates as passionate, headstrong and determined.

“I’m a strong-minded woman, but I don’t try to deny that I’m a female in any way,” says the singer, dressed in a black leather and knit ensemble. “A lot of women these days associate strong-minded with denying your sexuality. I think it’s really cool to be female.”

O’Riordan’s voice is soft, but she is not soft-spoken. Sharply opinionated, she seems mature beyond her 23 years, and she warms up easily to any topic—whether it’s shopping or politics. Although some people try to separate O’Riordan from the Cranboys, as her three colleagues have been dubbed by the Irish press, she is fiercely loyal to them.

Guitarist Noel Hogan, 22, and Lawler, 23, are soft-spoken and unfailingly polite—they even ask permission to smoke cigarettes as they sit in the restaurant for a separate interview, while O’Riordan is out shopping for jackets and boots. Hogan’s brother Mike, 21, the band’s bassist, is so untalkative that he typically skips interviews.

O’Riordan is clearly more intense and ambitious—the driving force behind a band that hired her when scouting for a new singer.

“She was very quiet and small and when we saw her at first you wouldn’t think she’d have a voice so strong...you’d think she’d be kind of timid,” Hogan says, recalling O’Riordan’s 1989 audition with her songs and keyboard for the group, then called Cranberry Saw Us (slur the last two words to get the pun). “It was obvious she could sing.”

The three musicians gave her a tape of a simple, four-chord instrumental they’d written. Four days later, she came back with the lyrics to “Linger,” inspired by her 17-year-old ex-boyfriend, who was at war in Lebanon and writing lovesick letters to her. Four years later, the song became an international hit.

The youngest of seven children, O’Riordan grew up wanting to be somebody whom people would admire. She adored her mother, who wanted her musical daughter to get a college degree and become a music teacher. When she was 4 or 5, Dolores would be placed in front of a class of 12-year-olds by the headmistress at school and asked to sing in Gaelic. As a teen, she was a punk-rocker who ran away from home.

I experienced a lot of betrayal... It’s not like a lovey-dovey world at all. A lot of songs were confronting different situations.

— Dolores O’Riordan

Now 23, O’Riordan has been married since July to Don Burton, 32, once a member of the rock band Alias and now a tour manager for Duran Duran. For O’Riordan, life has changed dramatically in the past year--and not only because she dyed her brown hair blond and got married. O’Riordan says she did a lot of soul-searching and growing up while she was hospitalized for three weeks following a ski accident in the French Alps early this year. Her maturation may be best typified by “Ode to My Family,” the first song on the new album, “No Need to Argue.”

“It’s about childhood, family and how important they are,” she says. “It will appeal probably to people who have left home and realized that the teen-age life is gone and you can never get it back.

“Suddenly you appreciate everything your parents did for you, even though at the time, when you were a teen-ager, you just couldn’t stand them. Then you’re older and you realize how cool your parents were and how nice your childhood was.”

The new Cranberries album is more strident and confrontational in content than the dreamy, ethereal debut.

“The first album was written when I was younger and just kind of getting into things,” says O’Riordan, who wrote—and performed—almost all of the material on the new album while on tour last year.

“When I was younger, people would manipulate me more. I was a bit too nice for my own good. You can have the greatest voice and the greatest ambitions, but if you don’t know where to tell people to get off...

“I experienced a lot of betrayal and it’s like, ‘Grow up fast,’ “she says, alluding to former associates with whom the band ended up at odds. “It’s not like a lovey-dovey world at all. A lot of songs were confronting different situations.”

In Ireland, the media likes to talk about the Cranberries as the Irish band that’s made the biggest mark in the United States since U2. But living far from Dublin and London, they haven’t seen much of the bright lights of the music business. They did meet U2’s Bono once at an Irish music awards ceremony. And O’Riordan has met Sinead O’Connor. “She seems very nice but a bit nervous,” she says.

When the Cranberries return to Limerick just before Christmas, they probably will be treated like stars for a few days—as they were last year after their tour abroad. People will stare, ask for autographs and want to hear stories about overseas. Then it will be a return to normalcy.

“Nowadays everyone is trying to be Mr. and Mrs. Rock ‘n’ Roll or whatever,” Lawler says. “It’s unusual to see normal, everyday people playing music.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.